For men of working age, not working tends to be a distinctly unpleasant experience. They exercise less than when they had a job, and they say that their relationships with family members worsen — despite having more time to spend with those relatives.

For women, the situation is more complicated. They’re more likely to say that their health and their relationships with friends and family have improved since they stopped working.

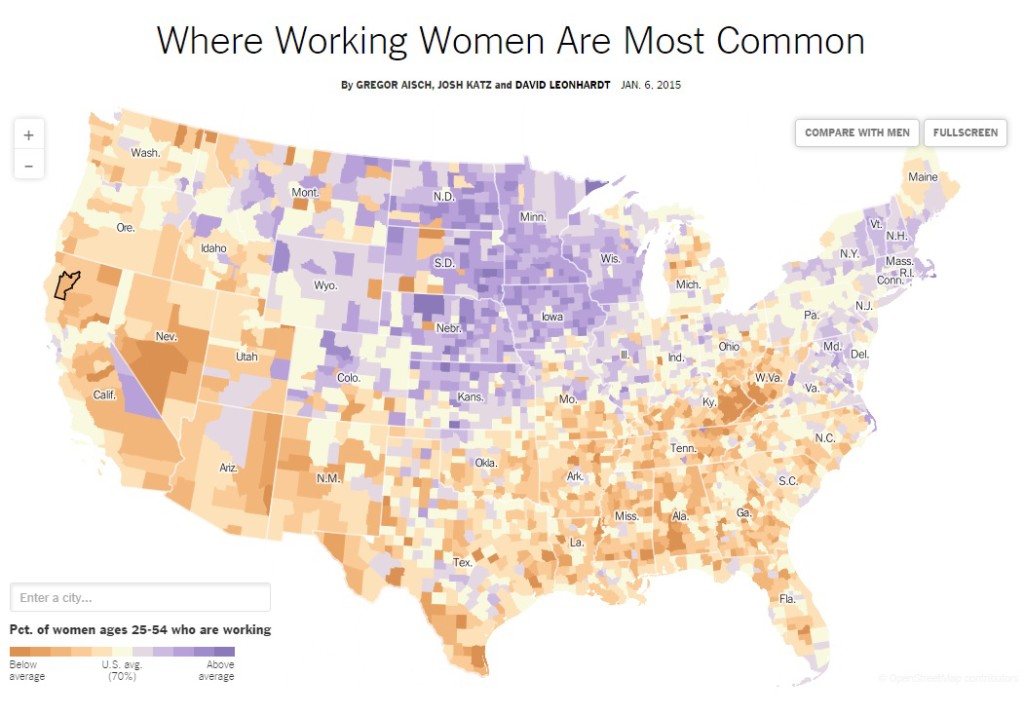

In a similar vein, the geography of female employment and nonemployment tends to be more complicated than the male geography.

The towns and counties where the lowest share of men between the ages of 25 and 54 are employed tend to be some of the tougher places in the United States to live, including Appalachia, Northern Michigan, the Deep South and the interior Southwest.

The places with low levels of female employment have a lot of overlap with these high-poverty places, as an Upshot analysis of census data shows. That’s hardly surprising: Lack of employment has a strong and obvious correlation with poverty. Yet the geographic patterns of female work also have more nuances than the male patterns.

Female employment rates are relatively low in some fairly affluent areas, including Utah and other heavily Mormon areas — as well as on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The East 80s and the suburbs of Salt Lake City may be very different places, but both have local cultures with a bent toward stay-at-home parenting, which still is far more likely to be done by mothers. In this way, they are extreme examples of a national trend: a modestly increased interest in full-time parenting in recent years.

On the other hand, female employment rates are notably high, especially compared with male rates, in New England and parts of the upper Midwest, which tend to be fairly well off. Female rates are also comparatively high in a swath of lower-income rural areas across the middle of the country. In all these places, education — the fact that women are now more educated than men — plays a big role in these contrasts.

Over all, the share of prime-age women with jobs rose throughout much of the latter decades of the 20th century, driven by the feminist movement. But the generally disappointing economy of the last 15 years — combined with the uptick in stay-at-home parenting — has caused the rate to fall since 2000.

Currently, about 30 percent of women between the ages of 25 and 54 are not employed, compared with 26 percent in 1999. By contrast, female employment rates have continued rising in most rich countries. The employment for prime-age men in the United States has been falling for most of the past half-century.

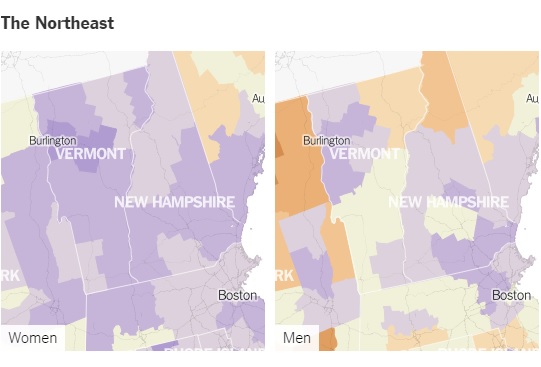

Throughout much of New England, employment rates for prime-age women — relative to their national average — are higher than rates for prime-age men. To be clear, men in New England between the ages of 25 and 54 are more likely to be working than their female counterparts. But female employment rates in some areas exceed the national average, while male rates tend to trail the national average. Why? New England is a highly educated region, with a large number of white-collar jobs, and women nationwide now are more likely to graduate than men.

New England also has a history as a center of manufacturing, which has long been male-dominated. As factories have closed in recent decades and white-collar work has expanded, women have been in a better position to take advantage. The pattern is evident in and around Boston and Burlington, Vt., but it’s especially strong in New Hampshire. In the northern part of the state, the prime-age nonemployment rates are nearly identical for the sexes, both around 25 percent.

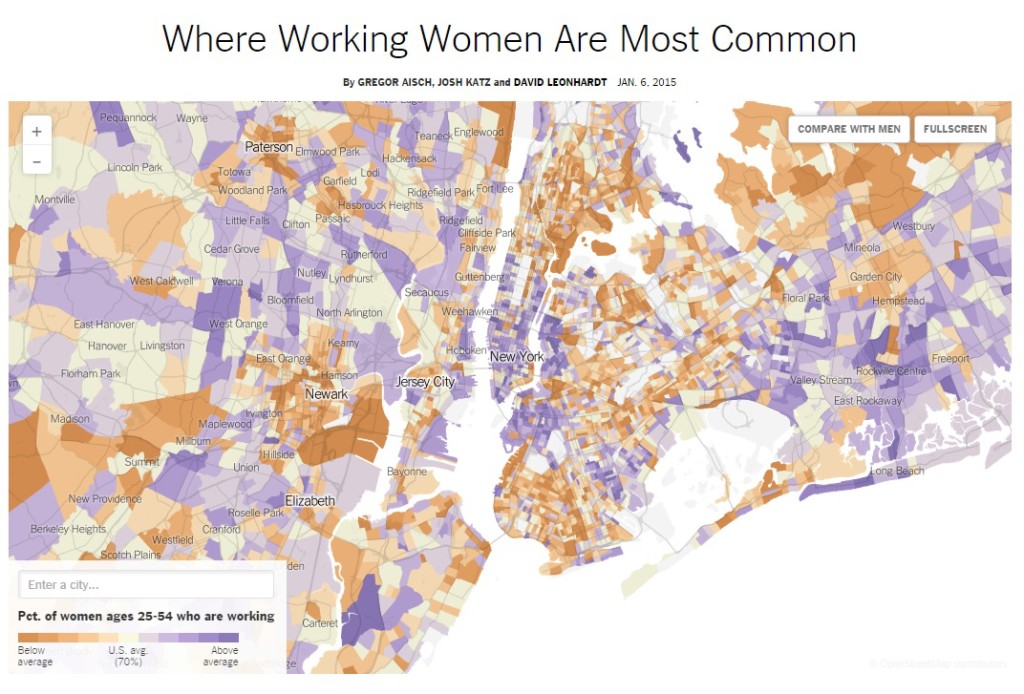

For men, nonemployment rates tend to be higher in poorer areas. That’s true for women, too — but their nonemployment rates can also be high in the richest areas.

On the Upper East Side of Manhattan, about half of the women who live on the blocks adjacent to Central Park do not work. On this strip — one of the wealthiest areas of the city — the chance a woman does not work is about as high as it is in some of the poorest parts of the country.

Sources:

The full text for this article can be accessed at New York Times Interactive. Last access Feb 2015. Downloaded from http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/01/06/upshot/where-working-women-are-most-common.html?_r=0&abt=0002&abg=0#/11/40.71/-74

Discussion Questions:

What do the women in your family do for work? Are they employed in a professional or semi-professional capacity or do they not work at all?

What social factors do you believe had the greatest influence on their choice (or lack of choice) of occupation?

If you grew up with a mother or mother figure in your household, did that person ever lose their job? If so, can you describe the impact on your family?

How might have the career choices of the women in your life impacted your decisions about what is possible and desirable for you, in terms of your own potential career trajectory?

Every household is different. In my house both of my parents work, but my mother makes the most money. She works two jobs, in the morning she works at a hotel doing room service, and at night she works at the hospital as a CNA. My dad only have one job, and still considered himself ” the man of the house” even though he makes less money than my mom. My mom always been determined and driven. Before she came to America, she was an accountant in Haiti. Her family wasn’t as poor as my father’s, but she had the privilege of going to college. Her main focus was to never rely on any man for assistance. Even though my mom works two jobs to provided for her family, my dad doesn’t agree with the situation. He believe the man should be the breadwinner. Due to our situation he cant complain because we have bills, and etc.

Growing up with a mother who is the breadwinner, it encourages me to work harder and strive. Seeing the table of women in certain areas that don’t work, really upsets me. Yes I understand they want to stay home and be the house mom, but they are relying on their husband financially. I feel like their stuck in time where women had to stay home and become a house wife, but times are changing and many women don’t like the idea to rely on a man for anything.

What do the women in your family do for work? Are they employed in a professional or semi-professional capacity or do they not work at all?

My mother in particular does not work, but all the women that are younger than her does. The ones that are employed do work in a professional capacity (e.g. pharmacist, teacher etc.). But keep in mind that most of these women are at least twenty years younger than my mom. The cost of living has become so expensive that it is difficult to live in the United States with only one income.

In Vietnam where my aunts are working, they are working because they do not want to be called “laborers”. People that live in the south are seen as more poor than the ones that live in the north (when you live in the north there are more cities). They want to own, my aunt owns her own pharmaceutical and she does not want to be known as the woman who lives in the south who is poor. Because she owns her own pharmaceutical, she feels accomplished.

How might have the career choices of the women in your life impacted your decisions about what is possible and desirable for you, in terms of your own potential career trajectory?

My mother was a teacher in Vietnam before she came to America and the aunts that reside in the United States are all educators as well. It made a huge impact on me because they influenced me to be a teacher. My grandpa also stated that he only wanted the family to have doctors or teachers. I could not be an engineer because that is considered a “male orientated” career. They wanted me to have a “female” orientated career that helps the community. So I had a very black and white future. Anything that wasn’t a teacher or a doctor upset my grandpa. (We’re really old fashioned.) I think also me being the second generation in my family affected my future as well. Both of my parents are refugees and it was difficult for them to raise me even till now. Me being the oldest of my siblings also made me their “test child”. So my success might not be as high as my siblings.

I found this article fascinating. I was aware that areas that are economically struggling would usually result in lower employment opportunities for first women and then men. Given that many of the jobs in these areas had been factory positions which historically (not counting times of war) had gone to men. It’s not surprising that when the factories shut down or shipped off that the first to be let go were women who probably held positions below management. What I had not thought of was that in economically upward or well off communities the number of women unemployed was virtually just as high. The second is by choice for the most part. The women in these areas are probably well educated and the average income more than enough to support a growing family yet still it reflects the fact that in America women by and large are expected to have their careers take a backseat to their husbands after children are born.

I am hesitant to make any assumptions that these women are unhappy with their choices or being forced to make a decision that they did not want to make. The issue is within the inherent biases of the workplace that tell women they need to make a choice between being a good mother or being obsessed with success. There is no equivalent standard for men. Society in affect tells women from an early age that we must choose. While men are not presented with that ultimatum.

The growing trend of more women graduating college then men and achieving success in careers that had previously been closed to them will be met with backlash as positions that had been thought of as for men become increasingly diverse. This diversity is good, workplaces benefit from a varied opinions and having both men and women or individual’s with differing views and upbringings can only prove to be positive as time passes.

The key to creating a more equal workplace environment is funding schools in these areas. The access to both health care and schooling I think lead to improved job choices and at that point families can decide equitably if one or the other parent wants to take time off from work to spend with the children.

My mother is currently the breadwinner for my family. She is originally a doctor in her home country Bangladesh, but, is a cytotechnologist here in the U.S. She had the choice to study to become an engineer, doctor or teacher. However, since engineering tends to be a male dominated field, she and her family felt it was best not to pursue a career in that field. Between her options of becoming a doctor or teacher, they felt that becoming a doctor would be a more stable career choice for her.

When my mother (and my family) moved to Canada it was very difficult for her to be able to practice there as doctor. Thus, we moved to the U.S. and she instead was (because of her Ph.D.) able to become a cytotechnologist. Her level of education helped her to have the job that she currently holds today. This has definitely influenced both my sister and I, in terms of the level of education we both hope to attain.

Every woman in my family works full-time and has always worked full-time; all of them were seamstresses working below minimum wage when they first arrived in America, specifically New York City. For my mother’s generation in my family, the child rearing responsibility was placed on the staff at public school, prep classes after the normal school day, and on weekends, until we were old enough to feed ourselves. This means from 8am to 6pm, every day of the week, year round, we were someone else’s responsibility. There was little family interaction, but our mothers’ work ethic had great impact on the female family members of my generation. Each of my cousins has started working part-time before the age of 16 and have eventually come to understand that our mothers’ sacrifices was to give us the opportunity to live comfortably and for us it meant making rent, paying for utilities, and making sure we did not go hungry. Personally, I started working part-time for the extra spending money because I knew my mother could not afford materialistic items that my peers had as a teen.

Though our mothers’ work ethics have rubbed off on my generation, I would have to say that education is the biggest factor in occupation. Four of five female cousins graduated from a specialized high school in New York City. The cousin that did not graduate is a receptionist. Two out of the four went to private universities, namely Wellesley College and The George Washington University, and went on to work for esteemed institutions. One graduated from a SUNY, and works as medical doctors’ assistant, and I will be graduating from a CUNY and hopefully landing a job at an elementary school after graduation as an educator. Education, and place of education, comes opportunity for work. My more successful cousins were recruited on campus and were offered positions before graduation, while others, and probably myself, will need to seek work on our own.

While this passage isn’t targeting mothers specifically there is a large population of stay-at-home moms that do not join the work force at any point after having kids. In the past few years I have had the experience of being close to two non-working moms. Both moms are around the same age and similar aged children, but have very different households .First is my older sister. She had attempted to go back to work after children but it wasn’t working for their family. They wanted more income but everyone was miserable; no one was sleeping, tensions were high, and they didn’t get to spend quality time together to be happy. Her and her husband did not want to pay for daycare due to the fact they could not afford it, and in their small-town daycare quietly is subpar. She sees staying home as a necessity for her family. She can make sure her kids are eating well and getting the attention they need while keeping the house and family in order, but they defiantly feel the strain of one less income. My sister is often to busy to think beyond what the days holds but does not see a career as a possibility right now.

The other mom that I have gotten to know is a stay at home mom in downtown manhattan. I was the family’s full-time nanny for over a year. They are a young family just like my sister’s, but they have the means to employ help and afford the best daycare and schools for their children. Things seem to run smoothly for this family unlike my sisters. They get adequate family time together as well as help like nannies to relieve some of the day to day stress of raising young children. In the year I was working with them, the mom has stating to me that she wished she would have done more with her education. Showing some hint of regret or want to do something more with her time.

A previous comment on this posting about a mother who felt bad about not building a carrier for herself made me wonder if this feeling of regret and guilt is a social norm for stay at home moms in the United States. My sister feels blessed that she has the ability to be home with her kids, but then again she doesn’t really have a choice right now. The Manhattan mom does have time to think and was starting to show some sign of regret. I am curious to see if my sister will share these same feelings once the kids have grown and life slows down a little.

Today, women may feel careers are important gages to be seen as successful women in society, but mothers feel a pull from both directions. No matter what a mother decides to do there is an underlying social guilt, weather it is to be there for the family or to build a career in society. It is no surprise to me that the more affluent areas have a higher percentage of working women. In these areas families have access to wonderful daycares and schools so some of the social guilt is relieved. They know they are still providing education, nutrition, love, and attention with these good schools, so they can do both, career and a family. The mother I worked for still felt the pressure to make mothering a full-time job from her small social circle even though they had the means to employ help and afford the best schools. The mother felt the need to play the part of a caring stay-at-home mom to prove her dedication to her family….All of her friends were also stay-at-home moms with a similar situation. Women like my sister, who do not have this access to decent schools or the means to pay for them, often do not have much of a choice to have both, career and family. They feel the need to do what is best for their family… or… guilt that they aren’t doing everything they can for their children.

I see women facing this decision constantly in this country between my female friends and family. It does seem a social norm for women to feel guilt no matter what they chose for their life. I have friends in Norway and Denmark who have never expressed this concern to choose. It would be interesting to see if this guilt exists in other nations as well. I know many scandinavian counties offer free daycare, accommodations for families, and existing paid maternity leave for an extended about of time. Do these accommodation in a more socialist states relieve some of this guilt to choose? it would be interesting to see a map of working women in these counties that provide the means to have both.

I won’t even go into the fact that our society doesn’t put this guilt on many men after starting a family….

My mother held various part-time jobs when I was growing up. She was either working for a travel agency or at the preschool I attended then she later began to work at the office my father works at. When I entered high school she decided to go back to school to be a guidance counselor. She worked extremely hard while in school taking on the roles of a mother, a student and a worker. I was inspired by her ability to take on these three roles with such determination. It was stressful for her a times but for two years straight she worked to get her master’s degree in school counseling. She now works in a high school as a part-time guidance counselor after having worked there as just a secretary in the guidance department trying to gain experience in the field for 4 years. I believe she is definitely happier now than she was with any of the part-time jobs she held while I was growing up.

When I was growing up, my mother’s main job was to take care of the family. Aside from that she use to make some simple hand made knit products to sell in the shops in our neighborhood. She is in her late fifties now. She sometimes regrets not building a currier for herself while she was young. Although she was the backbone of our family supporting physically, emotionally and economically at some extend with her knitting skills. She feels like she always depended on other through out her life. She depended on our father while he was alive than on us, as she got older. We as a children feel like she deserves every bit she owns and gets from us. But many times I do feel like she would have been a happier person if she was not financially dependent on others.

My mother works as a nurse for NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. It is not a glamorous job, but it’s stable. As a woman, my mother didn’t have many career options. She came to the U.S. when nurses were being recruited from other countries, like the Philippines. Nursing is/was considered a woman’s job so it was a fit for my mom. Her career decision may have been influenced by society but she was very savvy about her finances. She is my family’s bread winner and likely the most successful from her family back in the Philippines (She has 13 other siblings). My mom has inspired my sisters and me to pursue health professions. She backs us with her mind and her finance to ensure we have everything to succeed. Despite a gender disadvantage, my mom was able to rise above adversity. However, not all women are as lucky and equality should be paramount in the workplace.

In my family, my mother and grandmother both own a refrigeration business in a male dominated industry. Originally, her ex husband started this business with her until they divorced and she closed her baking shop to run Dorrington Refrigeration. By seeing my grand mom at her job all the time as a kid, I saw the struggle being in a business were you weren’t given the same respect as if you were a male. She was constantly proving herself and is the only woman to own a refrigeration business in the state of New Jersey today. My mother also is the manager of this company and is a strong independent woman. It is very hard for small businesses now a days but they work through it and have managed to keep their business prospering for me to be able to go to such an expensive school. I think the social factors which influenced and drove them was this inequality of woman in this profession.This made my mother want to succeed even more sand prove that gender doesn’t mean inequality and deserves equality.My grandmother always said “I’ve worked too hard and too long to give up because of a bunch of men trying to get in my way.” She is an inspirational woman.

I never witnessed my mother or a mother figure losing their job because they own a company but I have seen the tough times where they have came close to closing. This was hard to get past but they did. The career choices the woman in my life chose impacted my life dramatically in where I see my potential career going. By seeing them getting through tough times where there seemed to be no way out, I know that I can truly accomplish anything I put my mind to.That has been my state of mind and it is because of them that I think this way.