It’s easy to spot the girls’ section of a children’s clothes shop because most of it is pink and oriented towards the consumption of “princess” merchandise. A lot of parents complain that even when they insist that their daughters wear something different, pink seems to hold an irresistible allure for them. But is that really true? Is it inevitable that girls are born to grow up to prefer pink?

According to research the answer is “no.” Various studies have examined the issue of color preferences in different age groups. In the US most have found that babies and toddlers, whether male or female, are attracted to primary colors like red and blue. Pink doesn’t feature particularly high on the list, although it is more popular than brown and grey. Some studies of this age group have found blue is favored, others red, but they rarely find any strong gender difference expressed.

Hard-wired colors?

Cultural norms may also shape color preferences. In cultures where pink is considered the appropriate color for a baby girl and blue for a baby boy, babies become accustomed from birth to spending time wearing or even surrounded by, those colors. This makes it hard to know whether any preferences expressed later on are hard-wired. But a study from 2011 tried to get closer to discovering what’s going on.

When one-year-old girls and boys were shown pairs of identical objects such as bracelets, pill boxes and picture frames, but with one object pink and another of a second color, they were no more likely to choose pink than any other color. But after the age of two the girls started to like pink and, by four, boys were determined in their rejection of pink. This is the precise time when toddlers start to become aware of their gender, to talk about it and even to look around them to see what defines boy and what defines a girl. But just like adults, even very small children show biases towards their own group.

This group bias was also seen in another study where three-to-five-year-olds were given red or blue t-shirts to wear at a nursery. For one group, the red and blue t-shirts were constantly referred to, and by the end of three weeks the children liked everything about their own color group better. And that was just three weeks.

Gender becomes a key topic of discussion from early pregnancy onwards. When we hear the news of the birth of a new baby, there’s just one thing we want to know. Is it a boy or a girl?

You could argue that it doesn’t really matter what color babies are exposed to the most, but research tells us it can affect the way we, as adults, treat them. There’s one famous study showing that women treated the exact same babies differently depending on whether they were dressed in pink or blue. If the clothes were blue they assumed it was a boy. In recognition of this, they played more physical games with the perceived “boy” child and encouraged them to play with a squeaky hammer. Girls on the other hand, identified by their pink clothes, provoked soothing gestures. The women alternatively chose a doll for them to play with.

Keep in mind, no one is saying that pink is inherently a problem. Pink is not the “color of oppression,” as some have sarcastically noted. The problem is with the marketing of pink, because marketing is reducing girls’ choices.

Code Pink

In the marketplace, products that are pink and princessy now dominate girls’ sections for toys, clothing, and, well, almost everything. The marketing is so insidious that moms who were interviewed complained that it is virtually inescapable. Very young children are being socialized to think that “pink” and “princess” are the ONLY good choices for girls. So in other words, it wasn’t that the mon’s didn’t want their daughters to like pink or princesses. Far from it. It was just that they didn’t want their daughters to ONLY like pink or princess.

Pink princess marketing is forceful, even relentless, as it’s backed by many billions of marketing dollars. One might effectively argue that it’s not really a choice anymore; it is instead proscriptive. That is to say, it’s coercive, moreover, it takes deliberate advantage of a developmental phase that industrial psychologists are well aware of. Approximately two-thirds of preschool girls go through a phase in which they believe that their sex (the fact that they are girls) fully depends on external factors, like how they dress, because they don’t understand that sex is determined biologically. Fearful of losing their gender identities, and declaring their joy in being girls, they latch onto the most obvious stereotypical markers of their gender.

Teaching girls that they must subscribe to a conforming appearance, that they must look a certain way in order to be legible –to be a good girl — is not only disempowering, it can be destructive any effort to cultivate an independent and strong identity in young girls. Too often, it empowers young boys to be the “gender police,” as girls are called out for not nonconforming appearances and aesthetics.

Gender Conformity

Also a problem: The minority of girls who actively reject things that are stereotypically “girly” because they are gender-nonconforming (approximately 1 in 10 children, according to a recent Harvard study) are left out, socially outcast, and treated by peers and even adults as somehow defective. The Harvard study suggests that such children might leave childhood with PTSD!

The pressure to conform with male aesthetic preferences and gender stereotypes can have a major impact on a child’s early development. Even if the idea of color seems trivial, the way people act around color is not. Children are then left to negotiate the color trap as they are forced to confront these cultural stereotype in schools and across playgrounds throughout the United States and beyond. Social sanctions can easily give way to abusive behavior that sadly goes hand-in-hand with insisting girls must always look or “appear” a certain way in order to merit social recognition and not be labeled a gender deviant.

Boys, while not immune from similar gender stereotype pressures, do not suffer equally, because they are generally socialized to be powerful. Their social validation and self-esteem is, by way of contrast, generally grounded in their actions and accomplishments. Boys do, whereas girls are. Appearance standards thus are less of an issue for boys.

Likewise, it is boys and young men who, more often than not, are the ones calling out the girls when they don’t play their proper role or subscribe to the appearance standard, as is illustrated in the following video. This four year old girl offers an impressive response when a boy in her school commented on her appearance.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBhe8Ei8tnE

“I didn’t come here to make a fashion statement.” “I came here to learn not look pretty.” The wisdom of a child. We could all learn from her example.

Sources:

Article by Rebecca Hains, last accessed March 2015, downloaded at http://rebeccahains.com/2014/03/29/whats-the-problem-with-pink-and-princess/

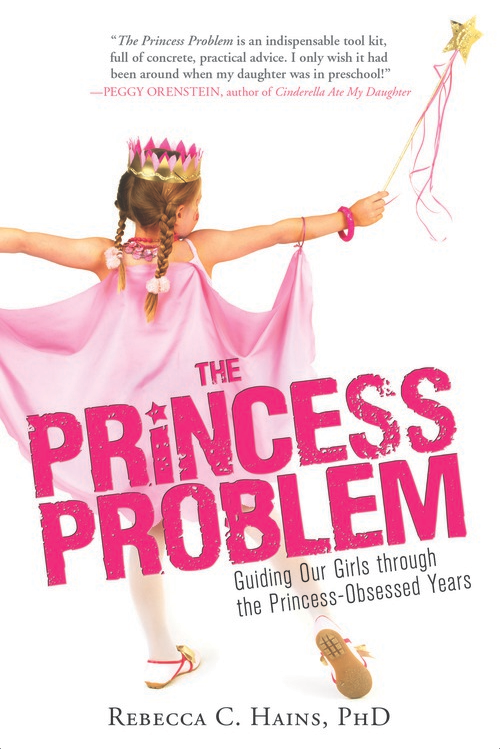

Rebecca Hains is a media studies professor at Salem State University. She is an expert in children’s media culture, media literacy, and media criticism. The article is based on her book, The Princess Problem: Guiding Our Girls Through the Princess-Obsessed Years.

Discussion Questions:

What do you think about the arguments upon which this research is based? How does it resonate/not resonate with your own experience?

Do you feel like your gender is something that comes “natural” to you, or do you feel there are aspects of gender culture that cause you to feel uncomfortable and/or “boxed in” as a result of public pressure and cultural expectations to conform in different ways?

Do you look to your gender as a source of power to express yourself? Or do you feel disempowered?

Leave a Reply