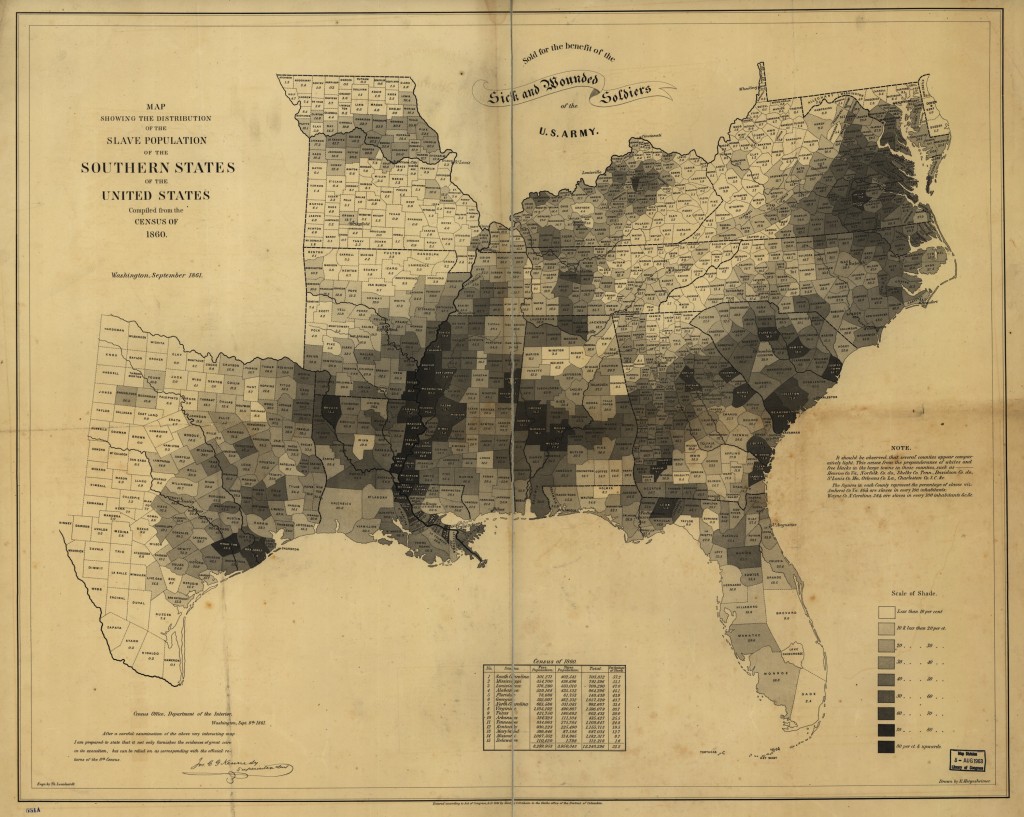

Slave Population, Southern States – 1860 Census

History

The American Civil War, fought between the years of 1861 and 1865 has often been called the first “modern” war, or as Richard Brown (1976) termed it, “the conflict of a modernizing society” (Brown, 1976: 161). Contemporary debates continue to flourish, although there is a pronounced tendency to “cherry pick” and distort the historical record. Partial truths, half facts, myths and in some instances bold-face lies animate the longest running trauma narrative in the history of United States – the history of the Civil War.

Traditional timelines date the beginning of the Civil War with the attack on Fort Sumter in 1861. As for the ending of the war, many point to the December 1865 ratification of the Emancipation Proclamation, whereas others cite the date Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865 at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia. And for reasons that I will explain here, there is a strong argument to be made that the war never really ever ended, despite the fact that almost 150 year of time have now passed since the last rifle shot was fired.

Although its duration was a mere four years, the Civil War established the high water mark for combat casualties. With well over a million casualties, a number which includes soldiers as well as civilians, it still stands as the bloodiest and most costly war fought in American history. According to Howard Zinn, “the United States government’s support of slavery was based on an overpowering practicality. In 1790, a thousand tons of cotton were being produced every year in the South. By 1860, it was a million tons. In the same period, 500,000 slaves grew to 4 million” (Zinn, 2010).

Put another way, 4 million slaves represented almost one out of every three residents residing in the South at that time (Ransom). When the war was ended, the economic impact devastated the North as well as the South.

Slavery was the engine of profit that turned humans into capital for the plantation (investor) class. During the year 1805, there were just over one million slaves in the United States. Their worth was estimated to be about $300 million dollars. Five years later, there were four million slaves, bringing the total closer to $3 billion (Ransom).

Now, if we were to look at this strictly in terms of the 11 states that formed the original Confederacy, 4 out of 10 people in those states were slaves in 1860 (about half the agricultural labor in those states). Put differently, slaves, who constituted around 38 percent of the population, provided 23 percent of whites’ income” (Ransom).

In the cotton regions, the importance of slave labor was even greater. In the seven states where most of the cotton was grown, almost half of the population were slaves; they accounted for 31 percent of the income of white people’s income.

Here’s another way look at this – the value of capital invested in slaves roughly equaled the total value of all farmland and farm buildings in the South. Though the value of slaves fluctuated from year to year, there was no prolonged period during which the value of the slaves owned in the United States did not increase markedly. In the book Crucible of the Civil War, Edward Ayers estimates that the monetized value of Southern slaves was greater than the combined value of all the railroads and factories in the North (Ayers et al, 2006).

Fast forward to our present time period in the United States and we find states’ rights arguments continue to hold sway in contemporary public discourses. States’ rights were invoked during the 1960s civil rights movement and have more recently been raised in connection with issues of governance that address ongoing discrimination (i.e. religious discrimination as this pertains to LGBT issues, access to birth control, gun control, in addition to other forms of gender and wage discrimination). Legislation aimed at curtailing the discriminatory actions of employers and corporations has also been opposed recently on the basis of the states’ rights arguments originally used to justify slavery.

The Biopolitics of the U.S. Civil War

The Civil War was the first U.S. war fought both over and on a distinctly human terrain. Going to war was deemed both logical and rational because keeping the South in the union was the only way Lincoln could ensure the legislative program to not only simply contain but to also control slavery could be accomplished. Social stability―or what some are prone to otherwise refer to as keeping the “peace” ― was only ever achievable through an act of war.

This means that the “perfect union” Lincoln dreamed of achieving was founded as much on the idea of the unification of states as it was a vision for achieving a unified labor pool of physically dominated and subordinated laboring bodies. What is worse, however, is that economic practices of human subjugation didn’t stop with slavery; labor practices were merely refined, laws were designed to be exclusionary, as they continued to target African Americans and others, who were marginalized and exploited in new and different ways.

In light of this, the purpose of the Emancipation Proclamation was never really fulfilled (as many believe it was). As it was conceived, the proclamation was superficially designed to serve/protect the interests blacks. But even Lincoln himself admitted that it was really conceived with two objectives in mind: 1) to further the economic interests of the Union; and 2) to help maintain control over the South by keeping them in the Union. Alternatively, had the South had been permitted to leave the union of states, scholars have argued the North could not have ever leveraged the means necessary to exert control over slavery (Ransom 1989; Ransom and Sutch 2001; Weingast 1998; Weingast 1995; Wolfson 1995).

Slavery helped to institutionalize hierarchical social relations based on notions of domination and subordination, which were paramount to efforts to secure the life and livelihood of all Southern whites —not just the ones who owned slaves. This explains then why people regionally affiliated with the South (and even some now who reside outside of the South) believed the war constituted an existential threat to their preferred lifestyle. Slavery was the glue that held the social order together.

Even outside the South, the subordination of blacks to whites as part of the “natural order of things” maintained currency. North and South were thus in many respects bound together as a union on the basis of the collective willingness of a people to ignore the contradiction of supporting freedom through slavery; both regions benefited from the structural legitimization, through force of violence and law, the linking of property rights with white identity and white bodies, and were committed to maintaining a system of race-based privilege.

Much as was the case with Southerners, Northerners also saw themselves fighting the good fight. In their view, they were reprising the Patriots’ struggle of the 1776 Revolutionary War. Unlike their neighbors in the South, the North was, ideologically, more invested in the idea of maintaining the American union at all costs. Even though many among them benefitted from slavery, there remained a wide-spread consensus among Northerners that slavery was antithetical to democracy and good governance. Nevertheless, if there was one idea that both sides could get behind, it was the idea that the principals of egalitarianism—life, liberty, freedom, and self-governance— ideals that breathed life into American governmentality, were in terms of design and intent dedicated solely to protecting the interests of property-holding white men.

White property rights were thus, by decree as well as declaration, institutionalized in the legal documents that established the founding of the U.S. republic. This basic sensibility was and remains sacrosanct, as we see even in our present era there are contested narratives about who made America “Great,” which speaks to who “built” and thus “owns” the property that is the nation.

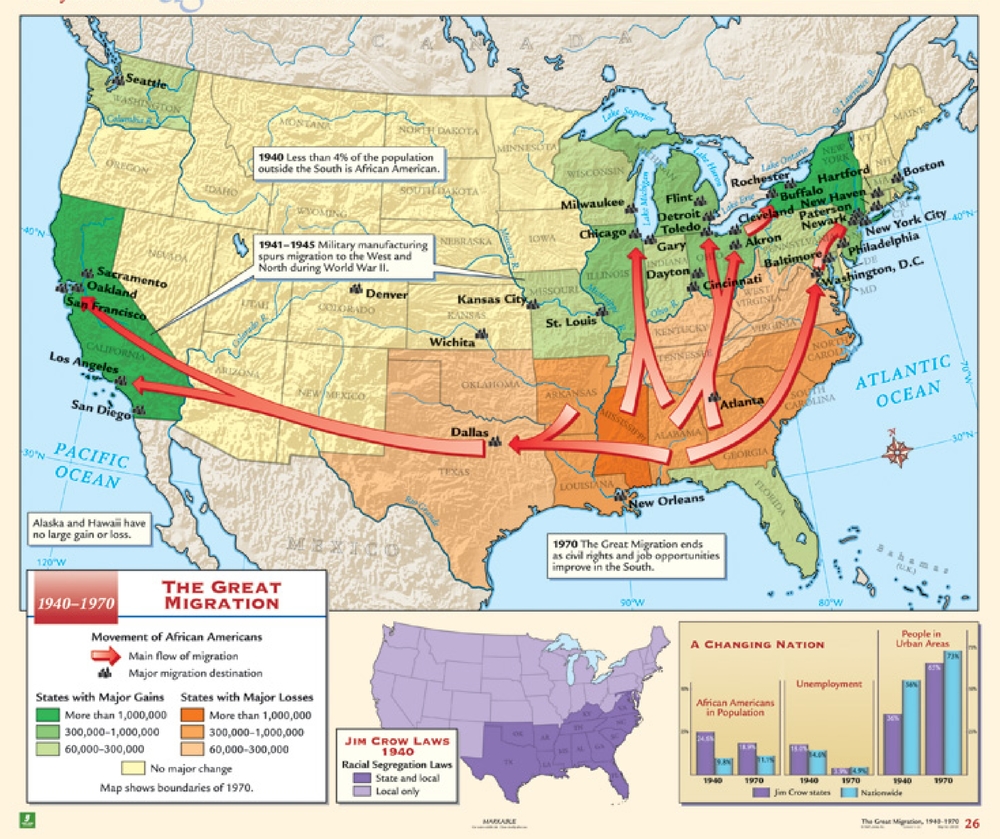

The Great Migration – 1920-1950

The early 1920’s were distinguished by one of the greatest internal migrations in world history. Fleeing the decaying Jim Crow system of agricultural labor in the fields and farms of the South, more than a million African Americans sought opportunity elsewhere and many moved to the industrial North, West, and Mid-west.

Unfortunately, the found little opportunity when they moved. African Americans were herded into exclusionary residential housing tracts – traditional ghettos, which expanded and morphed into new ghettos. Here, they lived under deplorable conditions, which was bad enough, but often they found they lived under the threat of “Negro Removal” that occurred in concert with large urban housing projects, many of which were little more than stacks of shacks built to house the migrants. To make matters worse, they often confronted overcrowded and neglected schools that provided poor or non-existent education for their children. Many of these “ghetto-like” conditions persist in the present day.

[Note: the term “ghetto” was originally used in Venice (the neighborhood of Cannaregio) to describe the part of the city where Jews were restricted and segregated. Playwright August Wilson also used the term “ghetto” in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (1984) and Fences (1987), both of which draw upon the author’s experience growing up in the Hill District of Pittsburgh, a traditionally black neighborhood that might be referred to as a “ghetto.”

Today, the term, while impolitic, is often used as slang or as an adjective to describe different social contexts. Urban neighborhoods in decline have been referred to as ghettos or nicknamed “the hood,” colloquial slang for neighborhood. It may be used to refer to inner city or black culture, or it may simply be used to designate something as “low class” and/or low quality. Some others, particularly rap artists in the hip-hop scene, have reclaimed the power of the work for themselves and have been using it in positive ways that are meant to transcend/overcome the word’s derogatory origins].

Post World War II

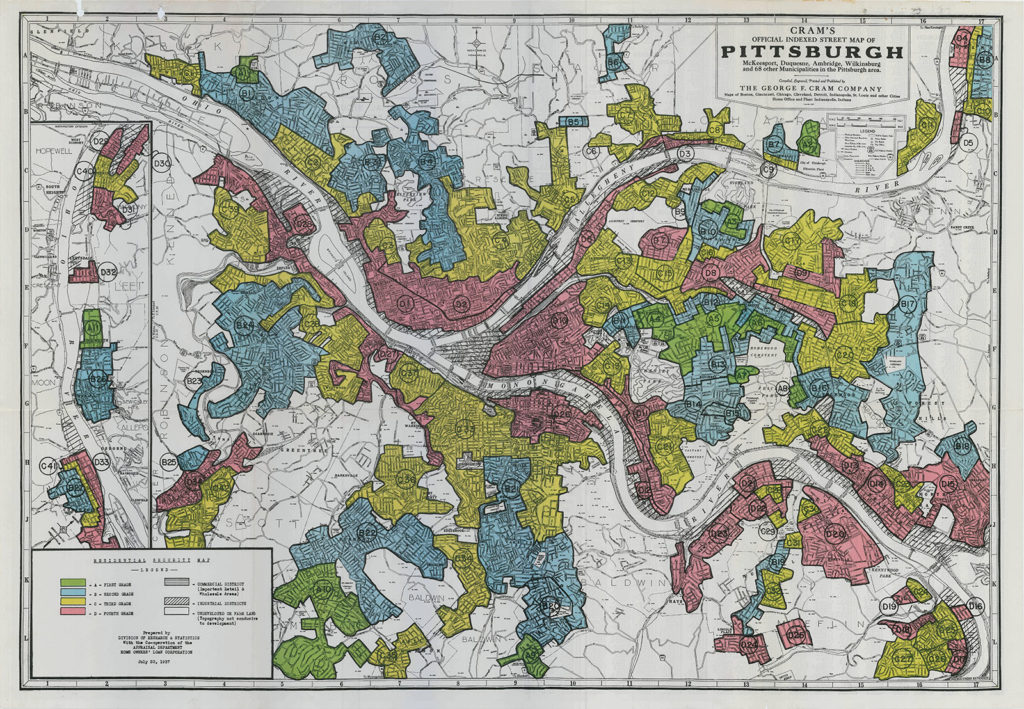

In the years following World War II, many white Americans began to move away from inner cities to newer suburban communities, a process known as “white flight.” White flight occurred, in part, as a response to black people moving into white urban neighborhoods. Discriminatory housing and real estate practices, like “redlining,” [more on the history of “redlining” below] were employed as a means to “preserve” emerging white suburbs, restricted the ability of blacks to move from inner cities to the suburbs, even when they were economically able to afford it.

In contrast to this, the same period in history marked a massive suburban expansion available primarily to whites of both wealthy and working-class backgrounds, facilitated through highway construction and the availability of federally subsidized home mortgages (VA, FHA, HOLC). These federal programs made it easier for families to buy new homes in the suburbs, but not to rent apartments in cities. Programs like the VA (Veterans Administration) were designed to help veterans buy homes, yet in terms of practice, African Americans who served in the war were not provided opportunity to access to their VA housing benefits.

In the same way that housing access was restricted, so was access to cars. Many car dealerships wouldn’t sell to or help underwrite car loans and insurance for black people. Even if they did sell cars to blacks, they were often quoted inflated prices (a practice that research has shown continues today). At a time when car ownership increasingly signified status for people, the inability to own and drive a car was materially and symbolically significant (Beras, 2016).

Deindustrialization and Suburban Sprawl – 1967-1987

Two main factors ensured further separation between races and classes, and ultimately the development of what people have come to identify as contemporary urban neighborhoods using the impolitic term “ghetto”: the relocation of industrial enterprises to poor neighborhoods, and the movement of middle and upper-class residents out of cities and into suburban neighborhoods.

Between 1967 and 1987, economic restructuring resulted in a dramatic decline of manufacturing jobs. The once thriving northern industrial cities underwent a shift from manufacturing to service occupations. This development occured in combination with the movement of middle-class families and other businesses to the outer suburbs, which created more economic devastation in the inner cities among poor people, many of whom did not own cars and could not relocate.

These changes fell hardest on African Americans, who were disproportionately affected, as they became unemployed or underemployed and were left with low wages and reduced benefits. Accordingly, a concentration of African Americans became established in inner-city neighborhoods, including places like New York, Chicago, Detroit, and other cities like Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

Additionally, a key feature that developed throughout the postindustrial era, which continues to symbolize the demographics of American ghettos is the prevalence of poverty. Poverty exacerbates the physical circumstance of social exclusion from other suburbanized or private neighborhoods. Given the difficulties of out-migration, the deteriorated economic and social conditions that produce a culture of poverty tend to reproduce constraining social opportunities and inequalities in society. The residents of these neighborhoods are often trapped and remain there for generations.

Contemporary African-American ghettos are characterized by an overrepresentation of a particular ethnicity or race, vulnerability to crime, social problems, governmental reliance and political disempowerment. City University of New York scholar, Sharon Zukin, explains that it is through these reasons that society rationalizes the term “bad neighborhoods.” Zukin points out that these material circumstances are largely related to “racial concentration, residential abandonment, and deconstitution and reconstitution of communal institutions” (Zukin).

The lack of autonomy and growing dependence on the state, especially in a neoliberal/capitalistic economy, remains a key indicator of the prevalence of African-American ghettos. This “dependence” is picked up on and circulates within the culture as a whole as a problem due not to a combination of individual and structural factors/institutional failure; rather, people tend to short-sightedly see the problems as the exclusive domain of individual failure, “bad choices,” and not “working hard.”

Despite this, the concept of “the ghetto” and the “underclass” (below working class) has faced criticism both theoretically and empirically. Research has shown it was not only race that accounted for neighborhood-level differences, but also social class (low income) in addition to public policies that allocated resources for neighborhoods differently; these patterns were found to occur with similar populations across cities over time. Neighborhoods that were predominantly low income and housed racial minority populations were hit the hardest.

To a large extent, the problem with our understanding of the ‘ghetto’ and concepts like “low class/underclass” is that they stem from a reliance on early 20th century ecological case studies (in particular studies from Chicago), which have tended to limit social scientists’ understandings of the more complex dynamics of socially disadvantaged neighborhoods.

“Redlined” Map of Pittsburgh

Social Inequality: Housing, Education & Wealth

Economic success in America is often seen as a reflection of what kind of family a person was born into, how hard they work, and what kinds of opportunities exist in the economy. The story, of course, is a bit more complicated than this. For as we all know, how well a person is positioned financially tends to reflect the well-being of the family they grew up in, how their parents and grandparents did, etc.

Family wealth can take generations to build. The process, by its nature, confers advantages that grow over time. If your great-grandparents bought a home, chances are that your grandparents inherited at least some of their family wealth from them. That means that your parents might have had opportunities to go to college that didn’t require them to take out loans. Or they might have gotten a helping hand with a down payment for a house early in life in a neighborhood with top schools. That means you got a great public education instead of a lousy one, allowing you to get into a good college and set yourself up to confer advantages on your own kids. And so on.

Discriminatory housing policies meant that racial and ethnic minorities could not secure mortgage loans (or if they did, the could only get them in certain areas). This resulted in a large increase in the residential racial segregation and urban decay that is evident in the United States today.

Consequently, there are lots of reasons that whites have so much more wealth than nonwhites. How the GI Bill and VA housing mortgage program played out is yet another one of those reasons. Whites were able to use the government guaranteed housing loans that were a pillar of the bill to buy homes in the fast-growing suburbs. Those homes subsequently increased their value in the decades that followed, thereby creating vast new household wealth for whites during the postwar era.

Noteworthy is how black veterans weren’t able to make use of the housing provisions of the GI Bill. And that’s because banks generally wouldn’t make loans for home mortgages in black neighborhoods. Given how African-Americans were excluded from living in the suburbs through a combination of deed covenants and informal racism, they were unable to use their housing benefits like their white counterparts. In short, their military service didn’t convey the same benefits to them as their white counterparts.

In short, the GI Bill helped fostered a long-term boom in white wealth but did almost nothing to help blacks to build wealth. We are still living with the effects of that exclusion today — and will be for a long time to come. The one big upside of the GI Bill is that it did pay for many black veterans to go to college and graduate school. While these veterans were often only able to choose among overcrowded black colleges (HBCUs), the influx of subsidized black students forced many white universities to open their doors to nonwhites, helping begin the great integration of higher education.

https://www.facebook.com/theinterceptflm/videos/157039208473392/UzpfSTExNTAzMzI1MTg6MTAyMTQ5NjA5OTc4MzU2NjY/

Deindustrialization,”White-flight,” and Braddock, Pa

Mapping Social Inequality

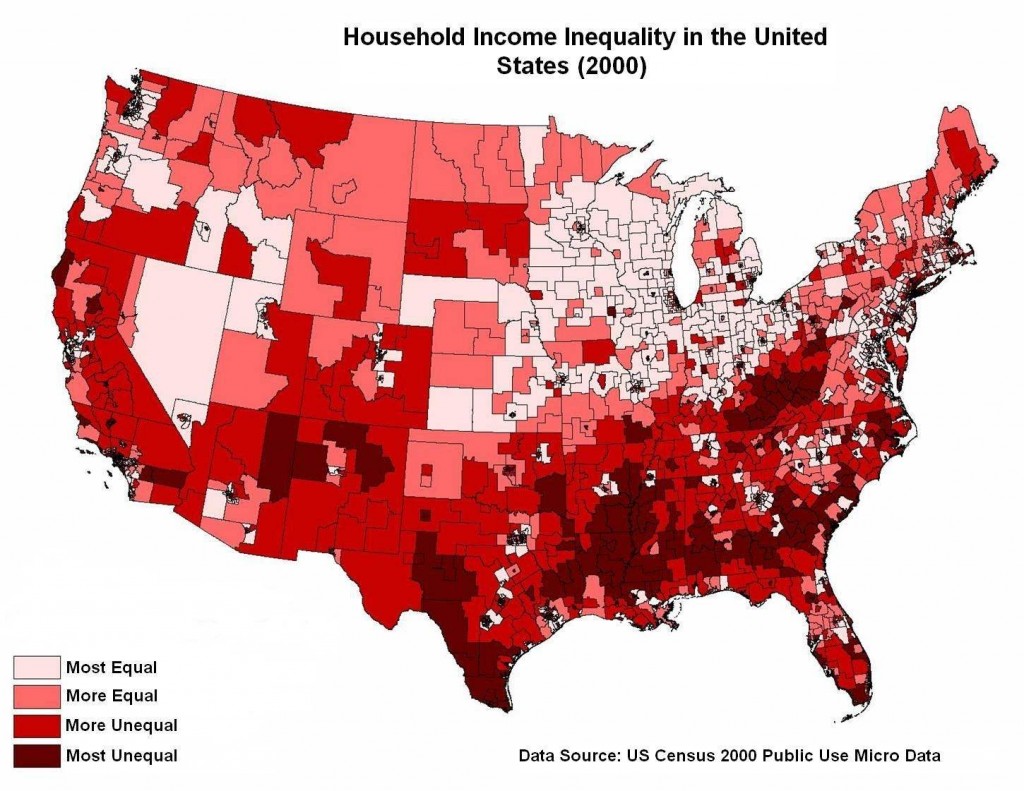

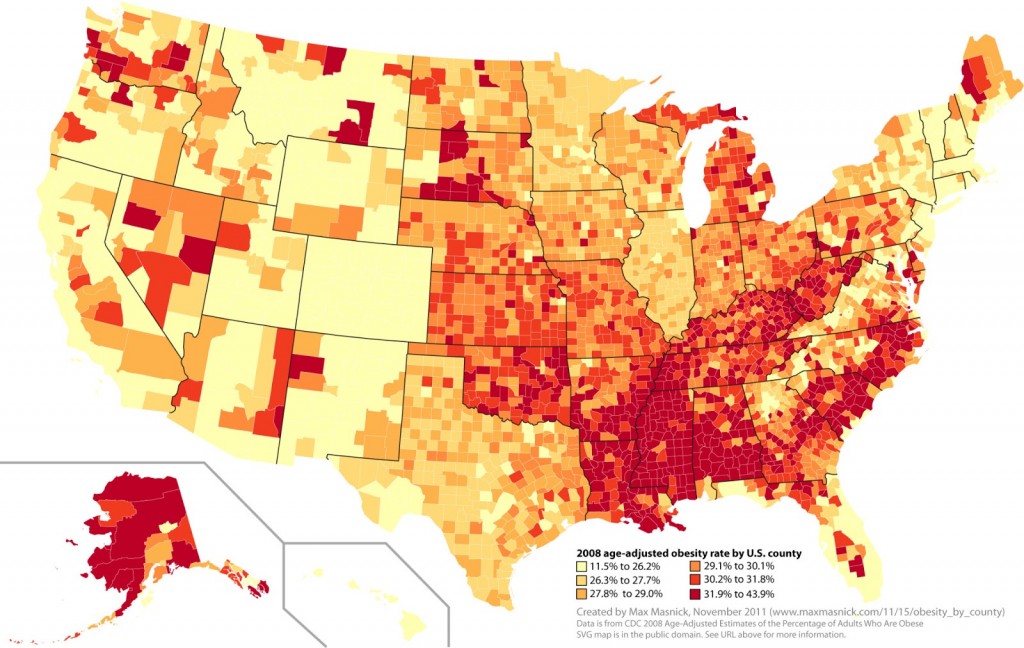

As it stands today, more than a century and a half after the U.S. Civil War was ended, racial inequalities in America are staggering by any measure. That is why it is important to remember the influence of the Civil War and the fact that it continues to cast a long shadow. The influence of the war helps to explain persistent patterns of social relations that include intransigent ideas about social hierarchies – i.e. “who is on top and who is on the bottom”- as well as the ongoing challenges of African-Americans to build wealth and achieve intergenerational mobility. To put this in perspective, let’s first take a look at a map that highlights the 11 states of the old Confederacy. Keep this map in mind as you continue to scroll down and look at the other maps that reflect social inequalities for income, health, and social welfare benefits.

The 11 former States of the Confederacy

Wealth & Income

The wealth and income divide are not simply due to individual behaviors (i.e. who works hard and who doesn’t). Rather, there are other historical and systemic social factors in play here.

In terms of income, the median income for nonwhites is only 65 percent that of whites. The wealth gap is even wider, with white families’ net worth six times that of non-whites. While individual research studies may vary, almost all of them calculate wealth by adding up total assets (e.g., cash, retirement accounts, home, etc.), after which they subtract existing liabilities (e.g., credit card debt, student loans, mortgage, etc.) The figure that results is one’s net worth.

A few statistics worth noting:

- According to the New York Times, for every $100 in white family wealth, black families hold just $5.04.

- The Economic Policy Institute found that more than one in four black households have zero or negative net worth, compared to less than one in ten white families without wealth.

- The Institute for Policy Studies recent report The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Divide is Hollowing Out the America’s Middle Class (RZW) showed that between 1983 and 2013, the wealth of the median black household declined 75 percent (from $6,800 to $1,700), and the median Latino household declined 50 percent (from $4,000 to $2,000). At the same time, wealth for the median white household increased 14 percent from $102,000 to $116,800.

Income Inequality – data from the 2000 Census

How did this happen? (reblog Brian Thompson)

The term “systemic racism” ruffles a lot of feathers. It often triggers emotional arguments about how people feel about racism and its effects. Yet concrete data over long periods of time shows very clearly that systemic racism exists.

Blacks were historically prevented from building wealth by slavery and Jim Crow Laws (laws that enforced segregation in the south until the Civil Rights Act of 1964). Government policies including The Homestead Act, The Chinese Exclusion Act and even the Social Security Act, were often designed to exclude people of color.

For example, in the 1930s, as part of the New Deal, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) created loan programs to help make home ownership accessible to more Americans. The Government created color-coded maps — green for good neighborhoods and red for bad neighborhoods — to determine who got those loans. Spoiler alert: many neighborhoods were designated as red because blacks and other people of color lived in them. This process, known as redlining, systematically prevented them from not only getting home loans but also encouraged developers in green areas to explicitly discriminate against non-whites. This often led households of color into wealth stripping “land contracts,” where they paid exorbitant prices for homes that they could lose very easily. Veterans, who were eligible for VA loans, could not use them in neighborhoods that were redlined.

These policies resulted in 98% of home loans going to white families, from 1934 to 1962. Not only did the ability to purchase homes give whites the ability to accrue wealth, it also attracted new businesses to those neighborhoods, which increased property values and allowed those homeowners access to other wealth building vehicles like going to college. As a result, wealth in the white communities compounded and passed to future generations.

Even after these policies were eliminated, the lack of wealth still prevented minorities from moving up to the green neighborhoods and kept the communities separated by race. Additionally, certain structures like a racially skewed criminal justice system and the tax code favoring the rich continue to contribute to this divide. The compounding effects of these types of laws have led to the wealth chasm that now exists. Even now, these effects are felt between otherwise similar families of different races. According to the Economic Policy Institute, the typical black family with a graduate or professional degree lagged its white counterpart in wealth by more than $200,000.

Racial wealth inequality is a huge problem that needs to be rectified. If the moral argument does not persuade you, maybe the economic one will. Considering how nearly 70% of our economic growth comes from consumer spending, as black and Latino households grow to become the majority of the population, their inability to spend due to the lack of wealth and paying down debt will slow U.S. economic growth. We owe it to ourselves and future generations to start correcting this problem now.

For more on this, see the full RZW study here.

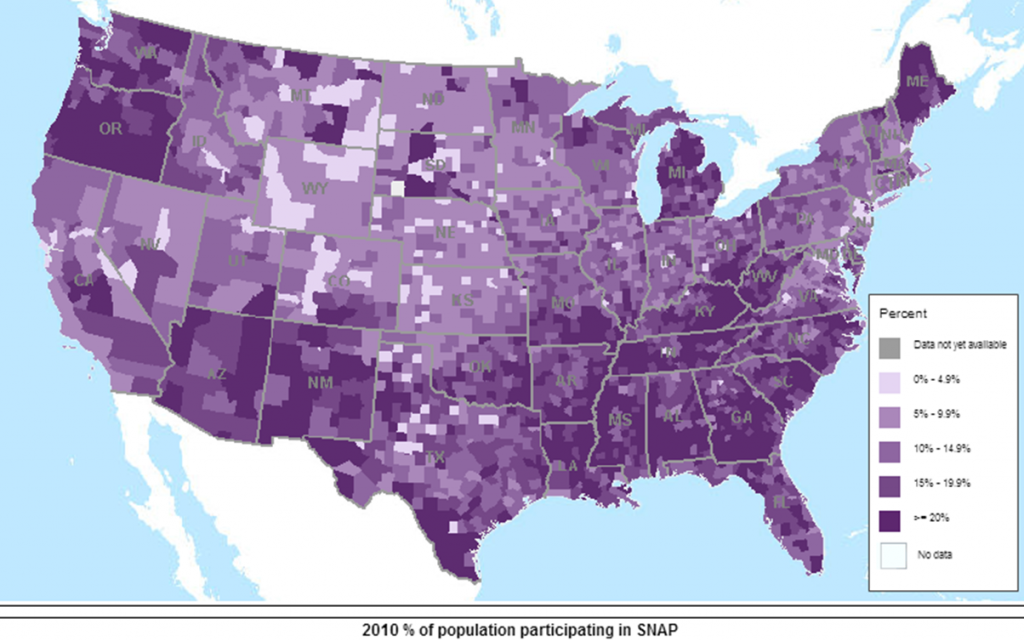

Social Welfare Benefits (SNAP) (still working on this)

SNAP Benefits Use (food stamps) – 2010

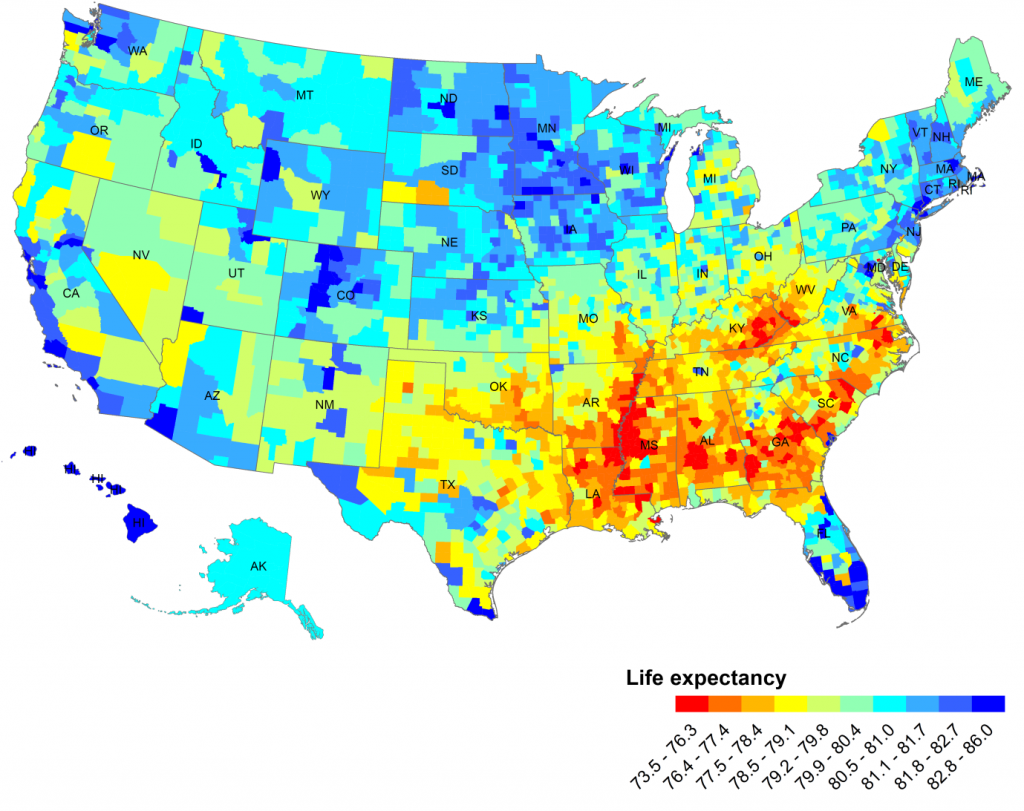

Health: Obesity and Life Expectancy (still working on this)

U.S. Life Expectancy By County

Summary

So why should you read or know anything about the Civil War? Why does it matter in a course on Race, Crime, and Justice? Well, I hate to be the bearer of bad news – it’s because the Civil War never really ended. “Everything about the Civil War is present tense,” says author C.R. Gibbs. “This is not settled.” The Southern and border states continue to be marked by social issues and problems that affect them at rates that are higher than those seen in the North.

Consequently, to truly understand modern-day social problems that involve issues of race, crime, and justice, one has to have some minimal level of competency when it comes to understanding the Civil War history of the United States. Present-day protests of contemporary KKKlansmen and supporters of “Alt-right” politics against Antifa (Antifascists) and their allies are modern-day examples of how Civil War era ideologies about race, dominance, and even “states rights” continue to animate people’s thinking about who are the rightful “owners” of American society. There is perhaps no better example than police brutality and the targeting of black men by police, which owes its roots to the slave patrols of the post-war Reconstruction era [slave patrols were hired by wealthy plantation owners – the first privatized police forces – to catch runaway slaves]. Likewise, we might point to the riots in Ferguson and Baltimore, which according to Gibbs, are merely match flares on a long historical fuse.

Keep in mind, the Civil War led to the passage of the 14th Amendment; an amendment that was designed to ensure that the U.S. federal government would protect African-Americans, even if (when) states did not. African Americans don’t feel safe in their cities and towns today and they don’t feel protected. And this is not happening only in the South; the North too has problems. In this respect, it is simply not possible to fully understand why some neighborhoods are poor and crime-ridden (or to use the impolitic term – ghettos) without first knowing something about the history of slavery and racial segregation in America; how these so-called “ghettos” were made by powerful wealthy white people (bankers, lawyers, and real estate agents). This helps explain on some level why people are rioting in the streets.

It’s, furthermore, not possible to understand why some marginalized groups rely on public welfare benefits without first developing an understanding of Who is poor and how they became poor. The vast majority of people on “food stamp” benefits are white people, even as the largest proportional representation of people on benefits are people of color. This paradox is not well understood by many Americans, most of whom rely on racial tropes to inform their understanding of who is poor and “getting a free ride” in the United States.

Put another way, the cumulative economic and social forces that gave rise to racial discrimination and the establishment of ghettos were the precursors to further social, political and economic isolation and inequality, which evidence material differences – differences that directly, indirectly, and symbolically define a separation between superior and inferior status groups.

Finally, I think that if you find it difficult to understand this history – and more specifically how modern-day social problems find their roots in the Civil War – you will find it difficult to understand some of the major issues and problems that currently afflict our criminal justice system – police brutality, disparate arrest and sentencing outcomes, the War on Drugs, Mass Incarceration. All of these problems find their roots in Civil War era politics and culture, which continue to resonate and shape our modern day social relations.

Discussion Question

How might historic social relations, based on the system of slavery, continue to be reflected in our contemporary social climate as it relates to the following: policing, the War on Drugs, the existence of poor neighborhoods and how we police them, firearms laws and the perceived need/desire for people to open carry, and public perceptions about “who is safe to carry” and “who is a threat?”

Sources

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States 1492 – Present. This citation is the opening paragraph of Chapter 9: “Slavery Without Submission, Emancipation Without Freedom,” Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2010).

Roger Ransom’s analysis is posted at EH.net, a publication of the Economic History Association. Last accessed Jan 16, 2018.

Edward Ayers, Gary W. Gallagher, and Andrew J. Torget (eds.), Crucible of the Civil War: Virginia from Secession to Commemoration. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006.

Charles and Mary Beard. The Rise of American Civilization. Two volumes. New York: Macmillan, 1927.

Louis Hacker, The Triumph of American Capitalism: The Development of Forces in American History to the End of the Nineteenth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 1940), p. 373.

“The Racial Wealth Gap: Addressing America’s Most Pressing Epidemic,” by Brian Thompson, 2018.

“How Redlining Blocked Black Car Ownership in Pittsburgh,” by Erica Beras, 2016.

Sandra L. Trappen, “Empty Metal Jacket: The Biopolitical Economy of War and Medicine,” 2016.

Although it is no longer legal, slavery is 100% still apart of our world but to a lesser extent. I believe our history, when it pertains to slavery, has a huge impact on our policing. Slavery is likely the greatest scar on this country, one even the constructors of our constitution struggled mightily with. The more we try to hide from this part of our past, the more distant we become from people whose ancestors suffered from it, and then we begin to create the race divide. It is obvious in the news and media today that this country is divided along racial lines. A majority of African Americans played a major role in creating this country, and their compensation, scars on their backs from an owners whip. I believe in society today, those exact scars lie on those African Americans who are racially profiled by the police. Our history has set us up for this failure in regards to the racial divide in this country. I strongly believe the early stages of this country have set up individuals, including police to allow racism into their homes and to live in a time where the race divide we face was acceptable. Maybe if we all continued to understand more about the disgusting institution of slavery we could better come together as Americans, so we can maybe rid the modern world of slavery still alive today, and to not bury the Americans who built this country in time as their owners did in the dirt and as certain members of law enforcement continue to do. Even our former first lady, Michelle Obama cannot escape the effects of racism as she says it best, “I wake up every morning in a house built by slaves”

When it comes to the data, it is historically connected to the period of slavery. These areas of heavily populated slavery indirectly correlates to some modern day issues. These areas are also areas where poverty exists heavily, the war on drugs has occurred, and many other laws have been in place to affect many low income families. Even today, you can see spikes in COVID-19 outbreaks from these areas. This could be a lingering affect from slavery. Because these areas were heavily enslaved, they might not have properly recovered from these times. Even though laws have been passed to free these slaves. Slavery is still showing affects today, even though we’re are far from the time of slaves, there are still lingering effects of it. These areas are being redlined, and that is adding to the problems. When it comes to police and the war on drugs, African Americans are statistically over represented in the data, and the war on drugs has targeted and hurt the African American community more than any other community.

The history of social relations still plays a big part in our society today. The war on drugs is an excellent example of that. African Americans are incarcerated at a much higher rate than whites. Even if the crime is the exact same, whites will be incarcerated far less than African Americans. In society today, there is the Black Lives Matter movement. This is the protest of police brutality and use of force. Many unarmed black men are shot and killed while armed white men are arrested. In poor neighborhoods, the police presence is much higher than wealthy neighborhoods. As far as carry laws go, almost anyone can go get their license to carry, but it is up to our society to say that an African American can legally carry without being a threat. All it takes is one nervous cop to be threatened by a gun that someone legally is allowed to have for someone’s life to be taken away.

Slavery is defiantly becoming more of a problem especially in todays society, but with that being said having your own slaves is no longer a thing in present days. There are people that judge and make racial comments towards others for just the color of their skin and its absolutely absurd. The police now a days have African Americans horrified to walk out of their homes because they believe it is going to be there last. The other day on the news there was a murder and it was a African American and white man involved and the media used the African American jail photo from a decade ago and they used a photo of the white man smiling. The media and news painted this image that these certain individuals were monsters and left out the part he was not the only one participating in the situation. The most tragic part about todays society is that mostly black people are targeted because most drugs come from inner cities that everyone knows that aren’t the best cities to be living in according to the stats. So when it comes to “who is safe to carry” and “who is a threat” will anyone have an answer for who can carry and who can not considering everyone believes if you are legally allowed to. carry you are instantly dangerous and a horrible person. When honestly that’s just to make sure you’re safe nowadays and its just ridicoulous to me and my family and friends.

Slavery is still very present in this world. Although, we have came along way in history we are often reminded of the injustice every time we turn the tv on or get on social media. The war on drugs targets African Americans more even though the same crimes are being committed by other races. I recently watched the news and came across a huge ring that was busted for drug use, all of the African American people who were involved in this ring were shown on television with their pictures, first and last names and even nicknames. The news cropped the original picture out were there were actually a few white people involved as well. They painted this image that these individuals were monsters and left out anyone else. So when it comes to the war on drugs then and now we have always had a disadvantage. When it comes to “who is safe to carry” “who is a threat” will we every really have the answer for that? You can legally obtain your gun license and follow all the rules but it only takes one time for a cop to see you and feel threatened, even if your simply trying to protect yourself. African Americans will never be viewed in the same manner if there carrying a gun as any other race. In all honesty African Americans will never be “free” or viewed as “equal”

Historic Social Relations based of the system of slavery most definitely reflects on the contemporary society we live in today. In relations to policing, the system itself has not modernized and continues using outdated policies in order to serve justice. With the war on drugs, it is statistically proven that more African Americans are arrested for drugs. However, it is also proven that Whites are among the highest drug user, so again policing and the war on drugs continues to follow ing the historic racist pattern. The way we police poor neighbors also relates to historical social relations because the systems fails them the ability to push based this barrier of class. Since these poorer neighbors cannot get past the “lower class”, policing within these neighbors is harsher and uses a lot of profiling. This again shows the idea of how historical relations continue to be perceived into todays society. As for firearms laws and the idea of who can and cannot carry weapons, Africans Americans are perceived to have a weapon at all times, so immediately this idea of “threat” comes into minds. Africans Americans are profiled and perceived to be always carrying guns illegally and they are a threat because of historical relations. All these topics tie into one another and continue to prove that this society is still in this historical racist idea. There has not been a change, but rather we continue to repeat history.

Throughout history we have seen how issues from the past have either never gone away or resurfaced again in a diffrent way. With me being adopted I have seen things from two diffrent perspectives, my adoptive parents are white and live in the subarbs and my biological family are black and live in projects. I was a young age when I started to understand that it wasnt common for a white women to take in a black kid, thinking back if the cops were called when I was with my mom in the subarbs the respond time was fast vs when I would visit the projects It would take them more then 20 mins to get there. Now the food stamps I honestly never really understood until I got older I worked at walmart as a cashier and would see a lot of familes of different ethincitys using food stamp cards. I know people who sell their stamps for money which again I don’t understand but I started thinking if its difficult for black people to find good jobs and opportunities that pay a wage to someone who could support themselves or their family I get why they do they need money. Now with me working at a gas station now I do see a bigger population of older white people who are using food stamps. There have always been poor white people with the caste system there was a hidden pedestal to create a division to keep black people at the bottom. I am not sure how I feel about gun control this will be the first year I can decide on if I want to have one in my life. I get people wanting to carry a gun but its like if your black and have a gun cops don’t tend to stop to ask if you took the legal route when getting a gun. Guns are supossed to make you feel “safe” but being black I dont really feel safe. Even if you get into a situaton where you have to defend yourself for black people I think that the senteces would still be unfair. If im being honest I get more scared when I see a white person with a gun vs a black person.

Slavery is for sure being reflected into today society, however no one in present days owns any slaves. There is people that do racial profile and judge base of a certain circumstance. As far as the policing goes, according to stats more black people are getting arrested by the police. Has it ever crossed ones mind that they are just the ones committing more crimes then the white people. The war on drugs is a huge problem in today’s society, no matter your race so many people do drugs. Mostly black people are targeted because most drugs come from the inner cities and most people that live in the inner cities are black according to the statistics. According to the maps where slavery started, is mostly where today the poorest neighborhood are located, In my opinion it is like that due to the fact no one else wanted to live their because of the past so the poor could afford it and really had no choice. Police do police these neighborhood more due to the stats proving there are more problems there. Coming from a split family of black and white regardless of who is carrying a gun, if you do it appropriate and use it accordingly if needed then there should be no problems regardless of the color. If you are doing things legally then you should have nothing to worry about. However in my point of view, the slavery is still reflected in today’s society the real question is when will it end?

The way that black people and minorities were discriminated against almost all of their history here in the United States does not make it shocking that they’re more than likely going to be discriminated against in United States systems and basic rights of citizens. African Americans suffer everyday from racial profiling. Police brutality is very obviously skewed towards black Americans. Black people are getting killed by police at 5 times higher rates than white people. Often times they are unarmed and not deemed threatening. We can’t be surprised that mass incarceration is a thing because police are unevenly disbursed in zone 2 or poor black neighborhoods. If there is heavier police presence in black neighborhoods they are going to be arrested at higher rates. Even though self reported crime shows that crimes that whites commit and crimes that blacks commit are nearly identical. So though there is not much of a difference in offenders based on race, there is a large difference in who is arrested because police presence is much heavier in poor black neighborhoods than in white suburban neighborhoods. It does not help that not many police that police these neighborhoods actually live there, if any. Police who were raised in small white towns are policing black neighborhoods. These police have racist tendencies and when they see a black kid carrying a pack of skittles, they panic and think he’s a killer due to media and pre-established thoughts and end up killing them or arresting them. The war on drugs caused a lot of issues for black people as well. They are being caught with a small amount of weed and getting life sentences out of it where a white person might get days. It also was directed towards black neighborhoods. I am not very educated on open carry laws but I feel that since it is a trend for black people to be discriminated against in every other setting including the grocery store, I doubt it would be any different for gun licenses.

Historic social relations, based on the system of slavery definitely continues to be reflected in our contemporary society today. As far as policing goes, you can surely relate what is going on today to the system of slavery that used to be present in the states. Police target areas where mainly African Americans live. The war on drugs also mostly targets African Americans. This shouldn’t be the case because today a lot of white Americans are also selling and using drugs but police don’t even look at these neighborhoods. As you can see in the maps of the United States depicting where slavery mainly was this is where the poor neighborhoods that mainly consist of African Americans are today! This has a lot to do with the “redlining” that happened and kept African Americans from getting home loans in certain areas. This just goes to show that the system of slavery is still reflected in society. These are also the neighborhoods that are the most policed. A lot of people also think that African Americans shouldn’t own guns. This isn’t fair because they are supposed to have the same rights as everyone else. Many white Americans think that it isn’t safe for African Americans to have guns because they think they will use them to commit crimes or violent acts. They think African Americans are the threat in society, meanwhile many white Americans are out committing crimes daily and no one blinks an eye! The system of slavery is still present in the United States today and sadly no one knows when we truly will all be “equal”.

My family has generally held the idea that hard work and dedication will lead to success based on their own experiences, having come from the poorest part of their country, and having found success based on that ideal. This has been ingrained in me since i was a little kid, and i think that that perspective has benefitted me in many ways. I do think that having that perspective has affected my opinion of poor individuals or groups and I’ve noticed that effect when interacting with those groups. When passing potentially homeless individuals on the street i often analyze their attire and make a decision to toss my spare change to them based on their behavior, signage, and manners. Ive noticed that if the person is dressed too well i become suspicious of them, because it affects my predictions of people in those circumstances.

I am well aware that there are more poor white people than black people. It is natural that based on the populations in the United States that there would be more white poor people, and more white people on food stamps.

I am typically a skeptical person, so there is usually some level of analysis that goes into the decision making process of giving people my spare change as i previously described.

I suspect that the reason programs associated with poor folks are considered welfare is based on the amount of taxes that are paid by that group of people. People that receive welfare benefits pay fare less in taxes than any other group, naturally. And so they are taking more out, than they are putting in, so-to-speak.

I don’t think that many people are receiving a “free lunch” so I’m not worried about that in particular. The amount of money lost through fraud is not significant when compared to the other social programs like Medicaid or Social Security. This doesn’t mean that I wouldn’t be happy if it was eliminated, but just that it isn’t a serious concern of mine.