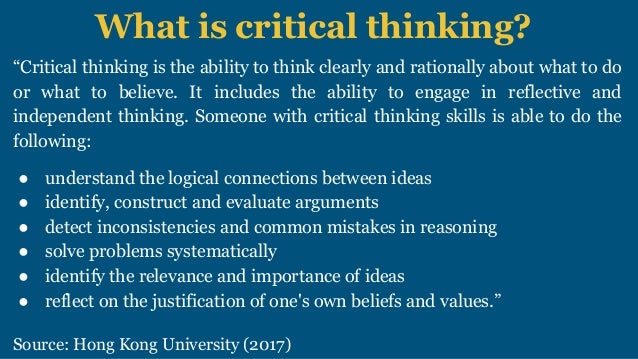

The term “critical thinking” is probably one of the most cliche terms in higher education today (“rigor” runs a close second). Given this, there’s a pretty good chance that every time you walk into a new classroom, your sage professor will at some point emphasize how one of the goals of their class is to “help students engage in critical thinking”- commence eye rolls. Unfortunately, the meaning of words becomes eroded when they are used as much as this.

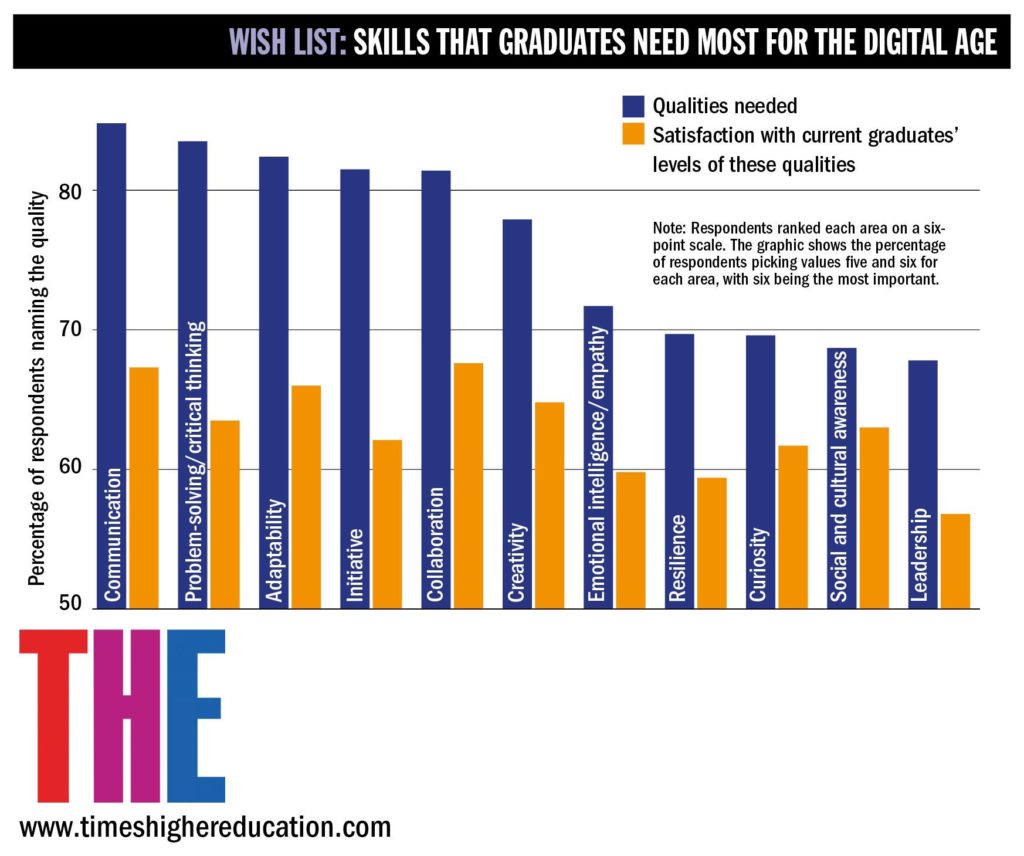

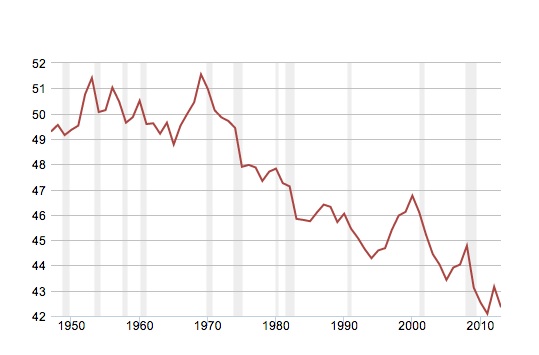

No doubt, this is frustrating for students, who I imagine may have buzzword fatigue. School Administrators and Ed Tech companies in particular love to hype critical thinking. And while there is ample evidence that suggests employers find critical thinking skills to be desirable, no similar evidence indicates that colleges and universities are delivering on their promise as such.

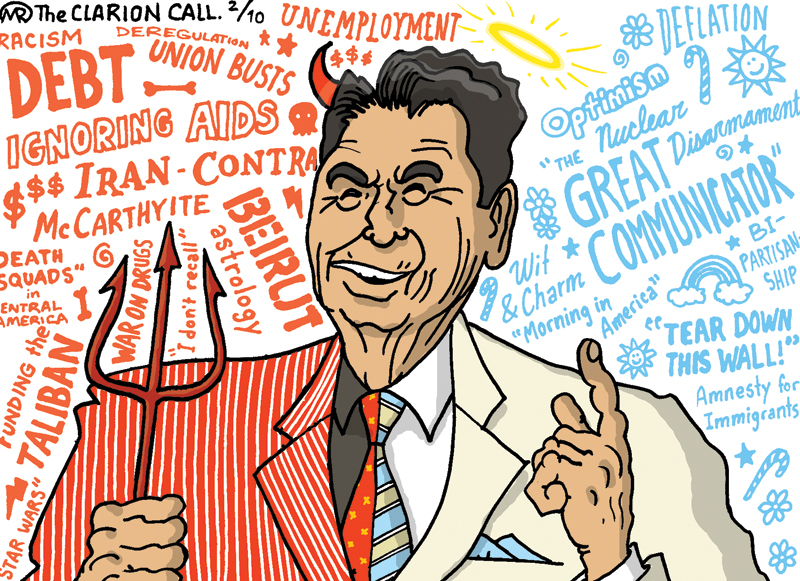

But of course, none of this is surprising when you take into account the history and evolution of public education in the United States. As it turns out, public schools continue to excel at what they were originally designed to do — they train obedient workers (not thinkers). The comedian George Carlin has a particularly famous riff one this (albeit it is very explicit), which you can check out on your own time on YouTube.

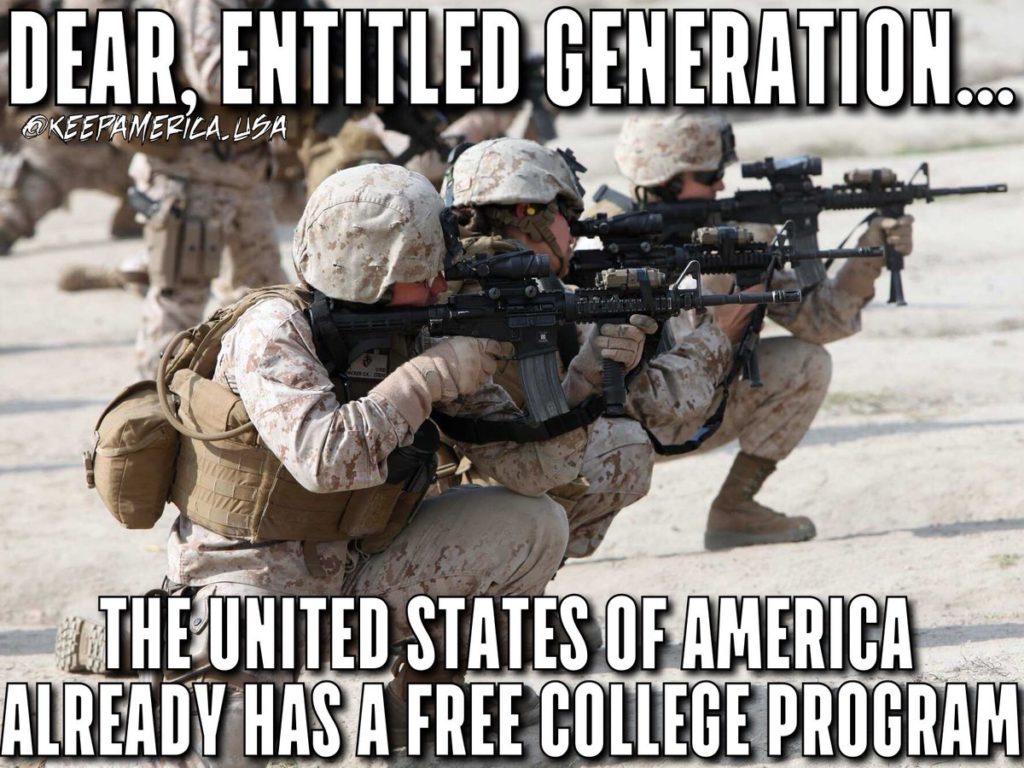

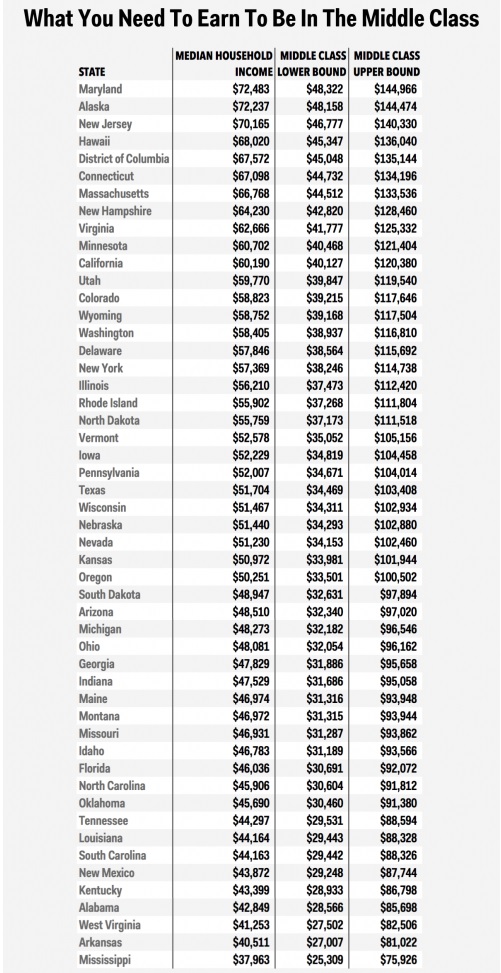

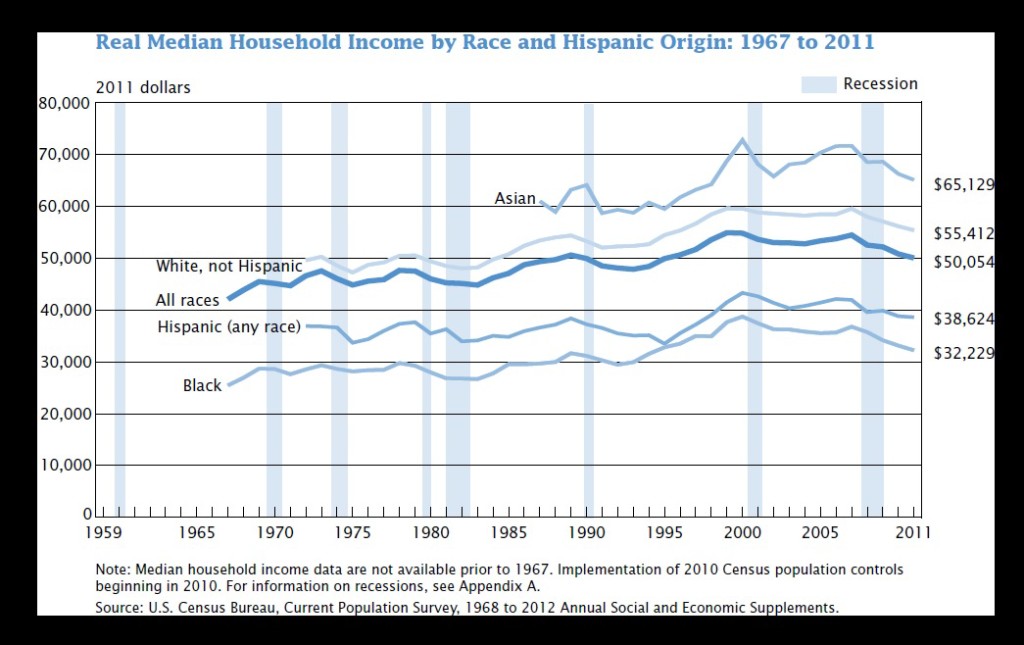

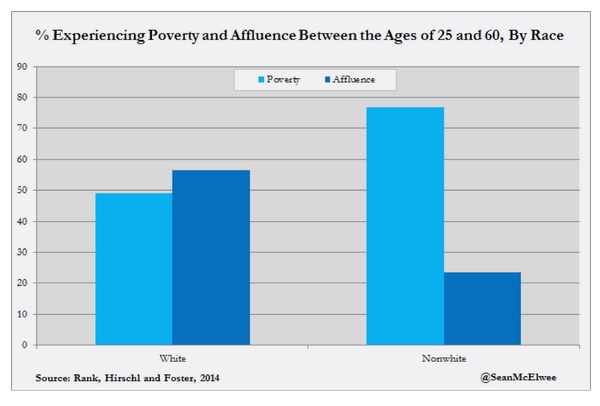

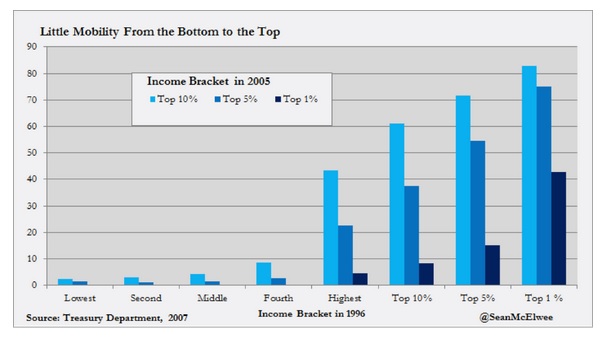

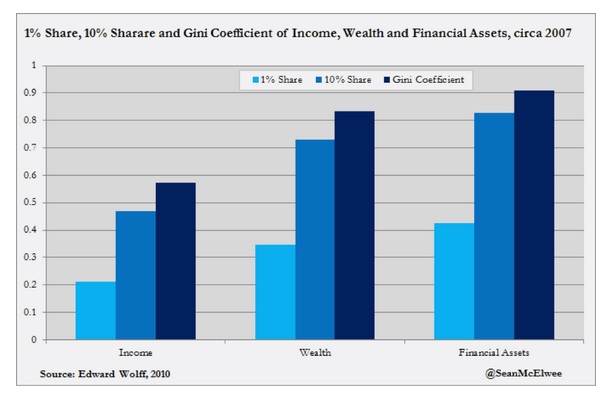

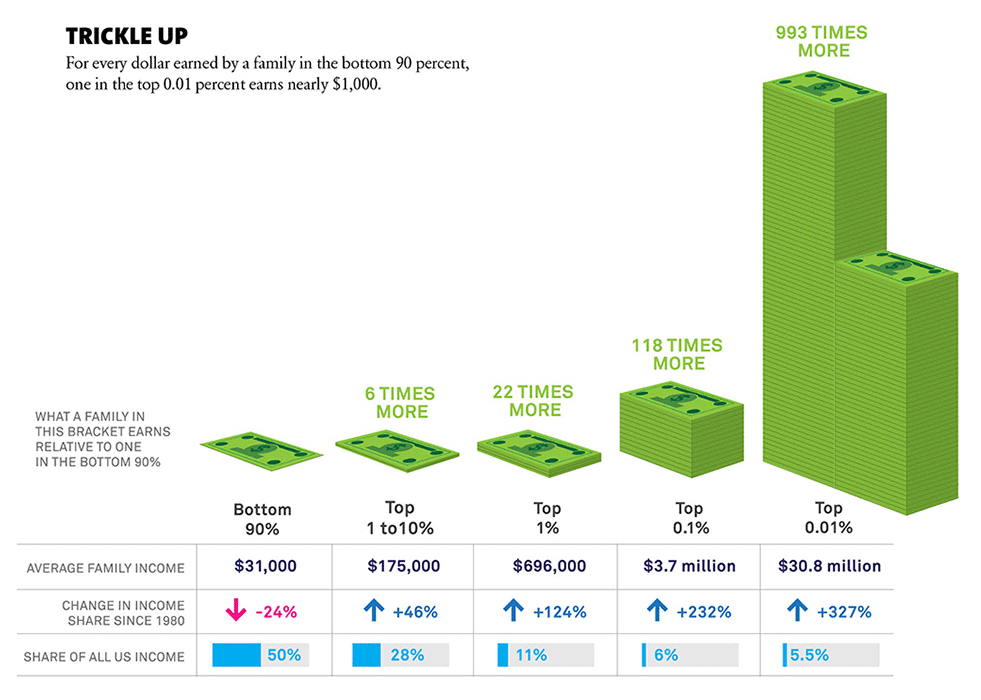

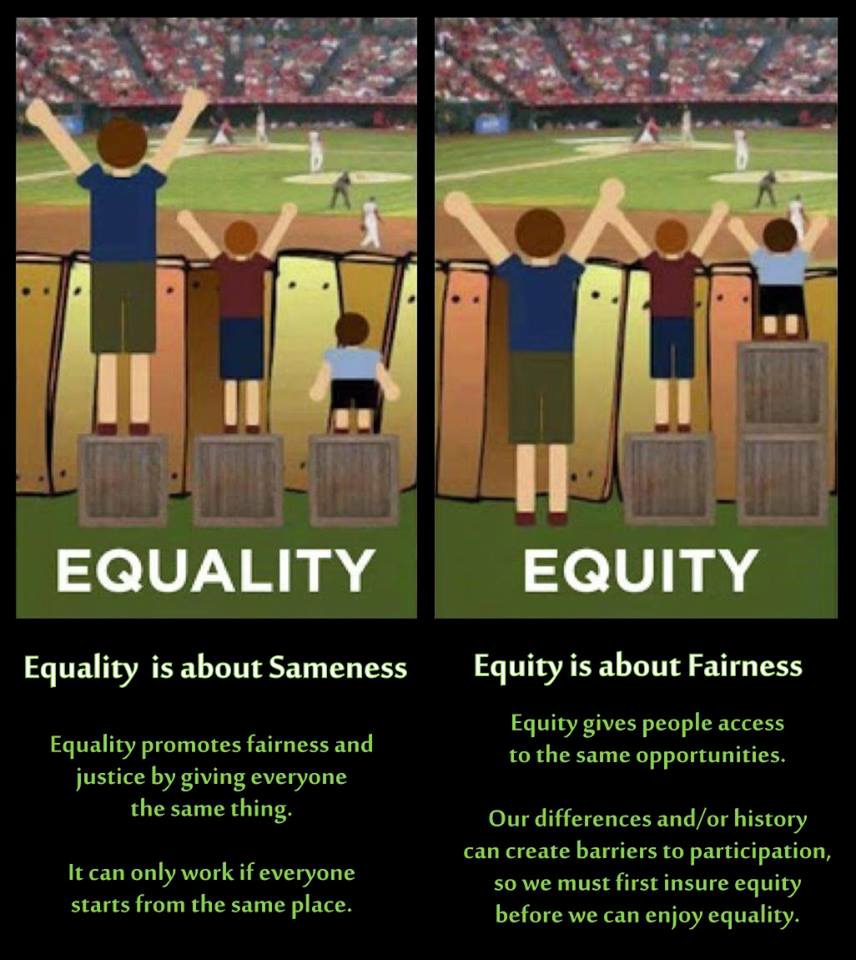

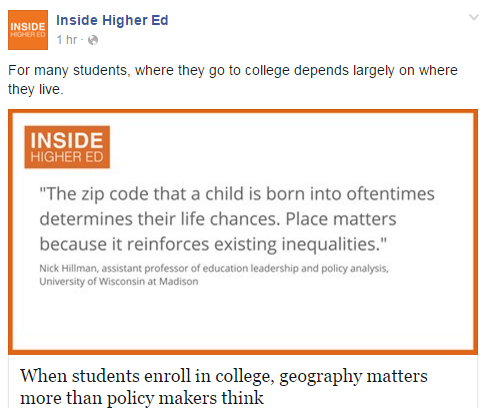

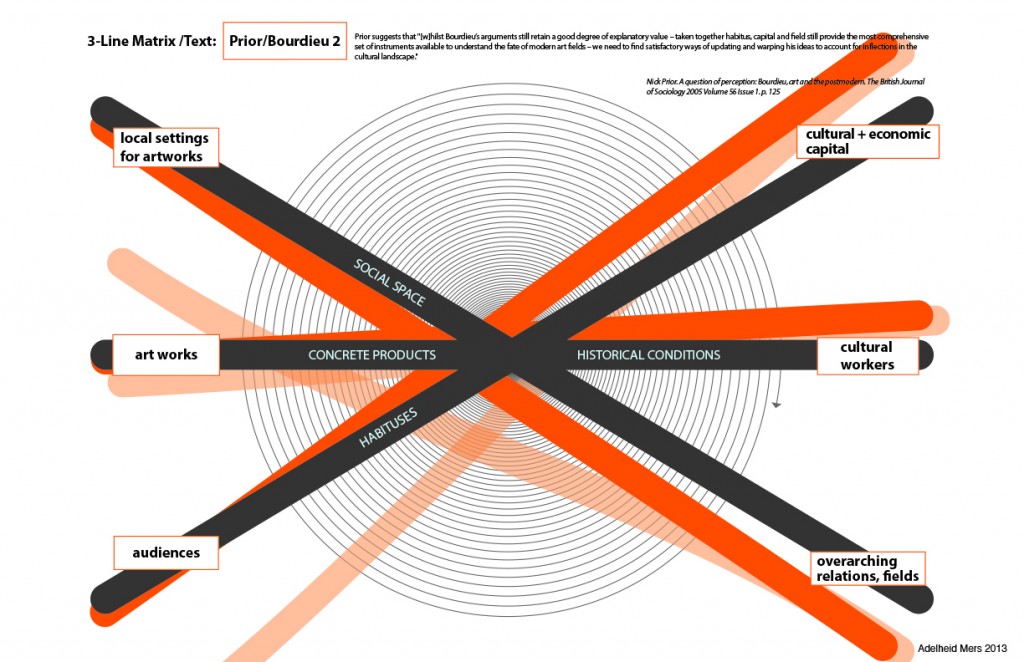

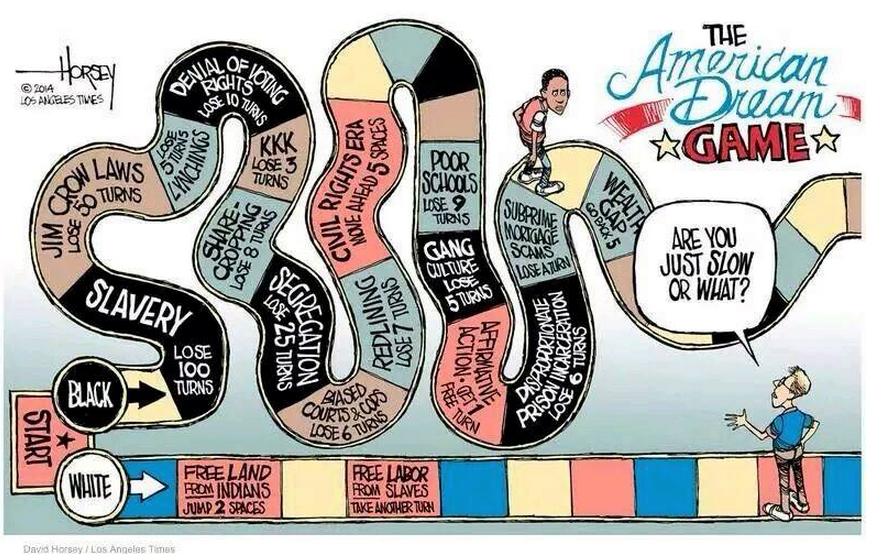

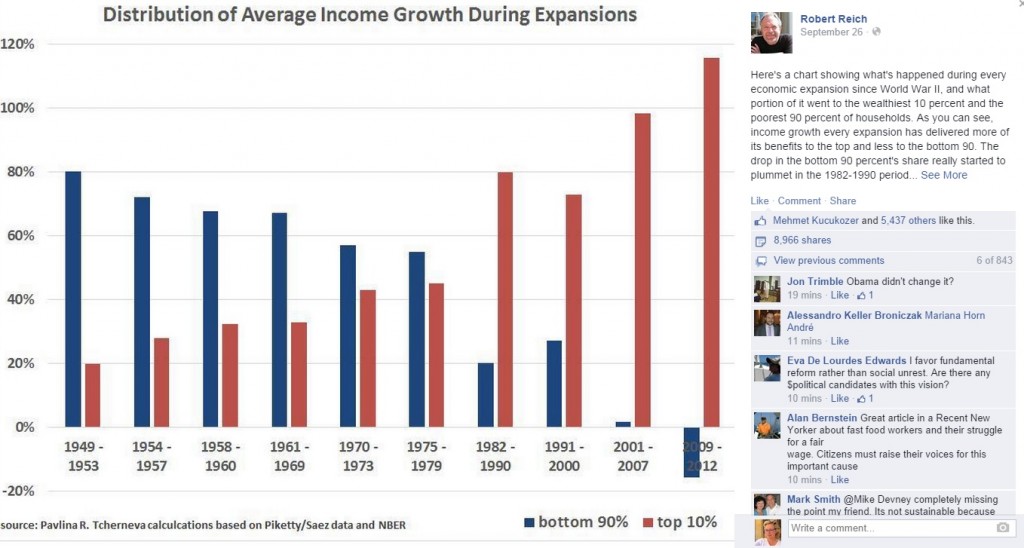

While education holds out great promise to be be an engine of social mobility in the United States, it remains deeply embedded in what sociologists refer to as the “social reproduction” of class privilege. This is why despite there being much evidence that attests to the ability of education to serve as a great engine to combat social inequality, there is similar competing evidence that suggests it can also reproduce and deepen pre-existing social inequalities.

One development that has contributed to the downfall of education in the U.S. in particular is the emphasis on testing and evaluation. This approach is far more rigidly ingrained in public schools, who have less autonomy than their private school counterparts to determine curriculum. Moreover, when testing does occur, its content and rigor are weighted heavily in favor of the middle classes and their offspring. The result is that the entire system of “objective testing” is essentially rigged against working-class and poor students (for complex reasons that are too lengthy to discuss here).

In the interest of staying on point, let’s just say that middle and upper-class families with resources, who can help prepare their kids for exams in ways that less advantaged families can not. In the case of the former, kids benefit from access to private high schools and they have the money to pay for tutors and extra-curricular activities, all of which supports access and admittance to higher education institutions. They are more likely to benefit from curricula in private schools that are more comprehensive and flexible (they’re not narrowly focused on testing), making it easier to teach those students critical thinking and leadership skills.

As a college professor, I work on the front lines where I am a witness to what our education system produces. I have seen changes occur over the years that trouble me. For one, I notice that an increasing number of high school graduates who enter my classroom exhibit difficulty expressing themselves clearly in speech and in writing. They similarly struggle when they attempt to execute what appear to me to be basic intellectual tasks (i.e. independently read a syllabus). Many of these same students could not pass a basic argument literacy test.

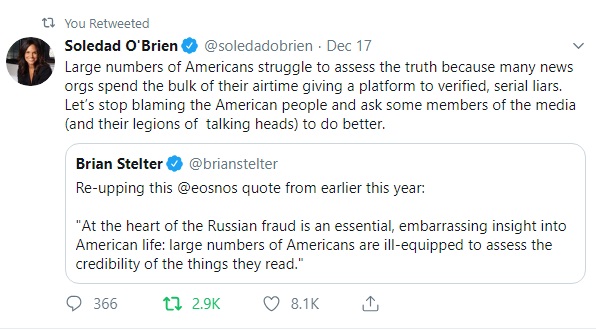

Even more concerning, there are relatively few students who can distinguish the difference between fact vs. opinion; they can’t tell you how science differs from non-science, or how natural science differs from social science, and so on down the line. “Fake News” barely scratches the surface in describing the problems that exist with media and information literacy in our present-day social landscape.

Put it different terms, critical thinking – defined more broadly as abstract reasoned thinking – has become an unfortunate casualty of the era of standardized testing. Testing regimes privilege memorizing facts and learning how to play word analogy games as a way to measure and assess “knowledge.”

What if I were to tell you that real life is not going to present you with options that are consistent with the choices presented on standardized tests? What if you took a class with me and I told you that I wasn’t going to test and grade your memorization skills? The latter should feel liberating, but students often feel intimidated because they haven’t been taught to think in a rational disciplined way.

Some of you, I hope, are nodding your heads in agreement, having already experienced the utter pointlessness of the test-taking trap. I imagine you have always sensed this. You knew something wasn’t right. But what could you have done to resist? Sadly, not too much.

When people are forced to forego more substantive approaches to education in order to play intellectual word games, they will at some point be left out in the cold. Their desire to learn will at some point become blunted and thus their learning potential will not be fully realized; they won’t be able to develop the thinking “muscles” required to engage in abstract reasoning (or they will become easily exhausted when they try).

Absent critical thinking skills, students will be ill-equipped to question and challenge the status quo. They may even give up on the idea of education altogether and quit as soon as they are able to work. Sneaky, yes? This is how obedience and conformity are learned, as resistance appears to be futile.

Rather than engaging in a fully developed critical analysis (which they most likely have not been taught how to make), students compensate by investing time and effort into trying to figure out the “correct” answer to a given problem. This has been, in their experience, the tried and true path to make the grade and to be rewarded and recognized as a “good student.”

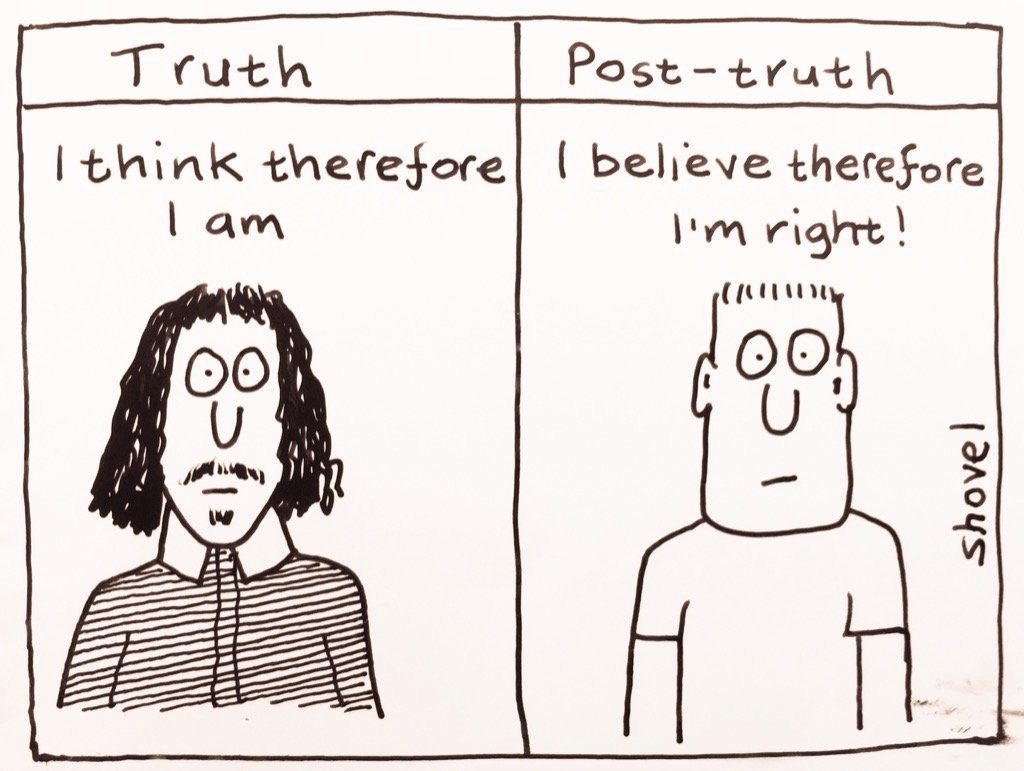

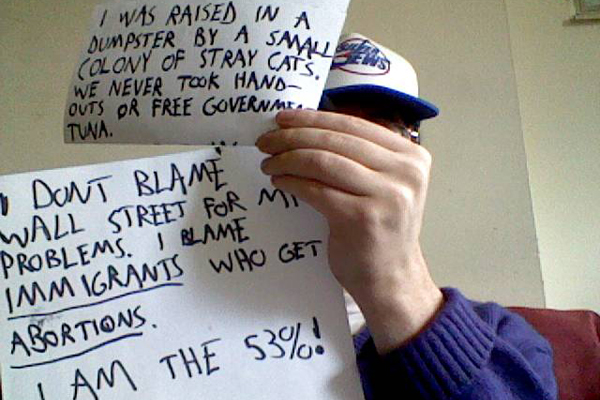

Another unfortunate result of the standardized approach to learning is that it encourages people to assign too much importance to their own thinking. Given how critical thinking skills are weakened/not developed, they sometimes cannot (will not) try to see problems objectively, as they prefer instead to rely on their own personal subjective “experiences.”

They trust their “gut” feelings and only that which they’ve seen with their own eyes because their reasoning skills are so poorly developed that they cannot think.

Given this, many students find it difficult to execute advanced learning tasks that require them to perform analysis/synthesis of information, as opposed to performing memorization and recall (they prefer the latter because they know how to do it).

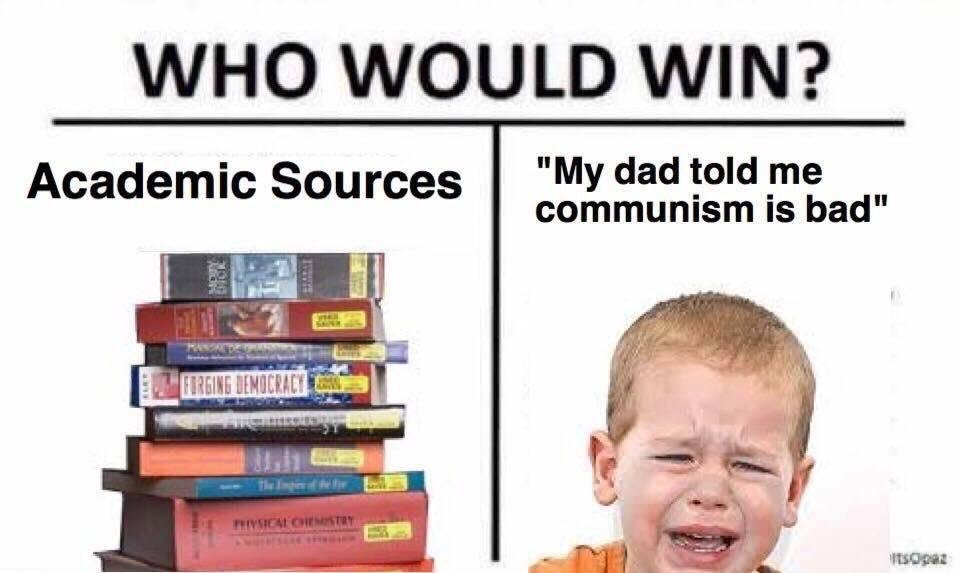

All of this, for obvious reasons, can produce frustration. And as I mentioned already, it causes many young people to become cynical and give up pursuing education. Disinterested and discouraged, they are less likely to pursue advanced learning (like higher education). They might feel they are not smart enough and they may even harbor a residual resentment towards so called “experts.” They may go so far as to cultivate a preference for media sources that tell them not to value expert knowledge.

That being said, I would be remiss if I didn’t call attention to the fact that everything that I just described here remains the students’ problem to solve (which seems unfair right?). In light of this, we have to do some work together to address where we go from here. But first, let’s examine some of the specific pitfalls that get in the way of critical thinking. The path is a bit long and winding. Along the way, we’ll look at some famous sociologists who called attention to these problems and proposed solutions.

Binary Thinking

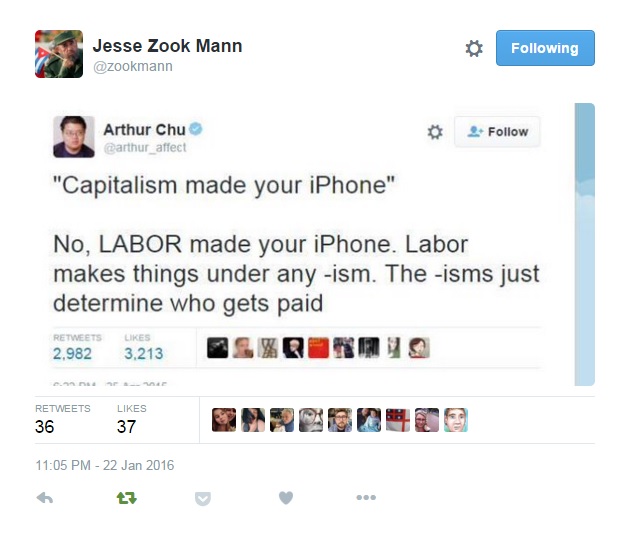

Binary thinking distinguishes an approach to problem conceptualization that reduces problems to two competing sides in order to arrive at a simple truth (i.e. right vs. wrong, left vs. right, liberal vs. conservative, pros vs. cons, good vs. evil). This framework tries to impose order and control on problems that are, more often than not, complex, nuanced, and dynamic.

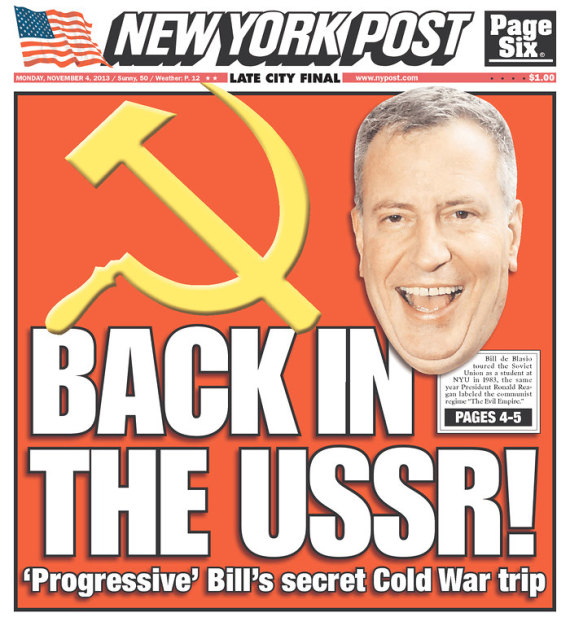

A derivative of binary thinking is what has come to be known in our contemporary moment as “both sides” journalism. This is the favored thought paradigm of the television era, where the best examples of this can be found on 24-hour cable news programming. The stars of these shows are pundits and talking heads who take two sides of an issue/problem and get into heated arguments with each other. Conflict is the “spice” that enlivens entertainment presented as information.

This development in our media landscape has been exacerbated by the proliferation of online news and political opinion outlets, including social media. As one study put it:

“this raises concerns anew about the vulnerability of democratic societies to fake news and other forms of misinformation. The shift of news consumption to online and social media platforms has disrupted traditional business models of journalism, causing many news outlets to shrink or close, while others struggle to adapt to new market realities. Longstanding media institutions have been weakened. Meanwhile, new channels of distribution have been developing faster than our abilities to understand or stabilize them” (Baum et. al. 2017).

It further calls into question the notion that American journalism should operate on the principle of objectivity. In the contemporary era, we have seen a noticeable shift, where journalists who once endeavored to be dispassionate about the subjects they cover, now operate like neutral referees in a cage fight.

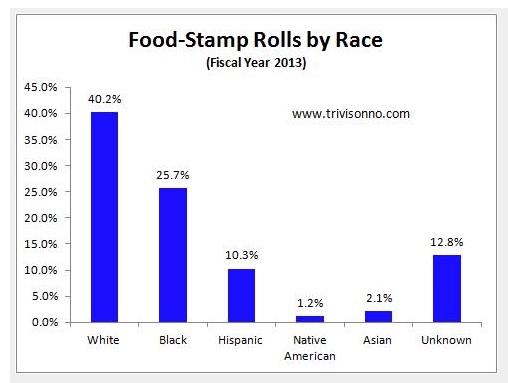

In taking pains not to take sides, they “both sides” every topic, where they contrive a match-up of two distinctly opposed sides of a given issue. But here is where the danger lies: in the process of doing so, they confirm each side has equal weight (false equivalency). That they do this, even in cases where one of those sides represents an extreme or fringe view (or simply a view that has been shown to be nonfactual/disputed by evidence), is plainly absurd. The result is that people with an appetite for conflict, dogma, and ideological thinking are left vulnerable to manipulation.

Illustration:

Do you believe in one or both sides of the flat vs. round earth debate?

Do you believe that there are two sides to every problem?

Do you believe that both sides have their own facts?

Again, while all of this might seem pointless if not ridiculous to many people, there are many in our society for whom this kind of thinking makes perfect sense. A large number of Americans have been ill-served by our corporate media. Their approach to discussing major social issues and problems is either so simplistic that it serves no particular value, or they give up, portraying problems as too difficult to solve.

The “all problems have sides” approach remains particularly problematic, for reasons that it is intellectually dishonest. Even worse, this framing has become normalized in our public discourse. Juxtaposing a liar opposite to an ethical professional, as if the two represent two legitimate sides in a debate, is a farce.

The Baum study authors conclude that the cognitive, social and institutional constructs of misinformation are complex and that we must be vigilant and seek input from a variety of academic disciplines to solve the problem, as the “current social media systems provide a fertile ground for the spread of misinformation that is particularly dangerous for political debate in a democratic society” (Baum et. al. 2017).

Jay Rosen, a journalism professor at New York University, points out: “The whole doctrine of objectivity in journalism has become part of the [media’s] problem” (Sullivan, 2017). When journalists use binary constructs to create structural and moral false equivalency, they become complicit agents, who undermine truth and understanding. All of this is a predictable outcome, given that understanding was never the goal here – manufacturing conflict is the aim of the game. These news programs don’t exist to inform you; they’re here to entertain you and sell advertising.

A better and infinitely more responsible approach would be to report things fairly, accurately, and comprehensively. Journalists might further acknowledge their biases upfront instead of trying to exist in a magical bias free-zone.

One of the problems that we are left with here, even when we aim to do better, is that sharing factual data with the public does not always change strongly-felt but erroneous views that conflict with people’s personal beliefs and feelings (facts being immaterial).

“I feel like” and Using the Personal Pronoun “I”

Ever notice how often a problem comes up for conversation or discussion and instead of addressing the problem objectively people respond by saying something like “yes, but I feel like” and they proceed to relate the problem to their own personal experiences? Notice how those same people are more committed to defending their feelings much harder than facts?

Lots of people do this. It’s a very subtle and often unchecked form of narcissism that allows you to divert attention away from an issue or problem that may be controversial (or you simply don’t know much about it), where you default to the subject that you are most comfortable discussing – yourself! To some extent, this is to be expected, considering how today’s students have come of age in a time of growing diversity and political polarization. No one could blame them for wanting to back away from confrontation (Worthern, 2016).

In North American English, “I feel like” and “I believe” have in the last decade come to stand in for “I think” (Worthen, 2016). Sociologist Charles Derber describes this tendency as “conversational narcissism.” Often subtle and unconscious, it betrays a desire to take over a conversation, to do most of the talking, and to turn the focus of the exchange to yourself (Headlee, 2017).

To illustrate, people say things like “I feel X about XYZ problem.” What would be better is for them to say something like: “I think, based on XYZ evidence, that the idea of X appears to be supported.” In the case of the latter, the speaker “de-centers” themselves (emphasizing evidence and conclusions, not personal beliefs) and uses objectified scientific language.

Note: if you are taking my course in Research Methods, you will need to demonstrate to me that you can write using objectified scientific language.

Worthen points out that when we use language like “I feel like” we are playing a trump card. And that’s because when people cite feelings or personal experience, “you can’t really refute them with logic.” Why not? Because that’s like saying they didn’t have that experience or that their experience is not valid. “It halts an argument in its tracks” (Worthen, 2016).

The recourse to feelings is problematic because you are limiting what you can discuss/engage within the narrow confines of your own personal experience. This is not a solid ground upon which you can build knowledge of a subject; subjective perspectives and personal “feelings” are not frameworks that facilitate the analysis of complex problems.

I write this with full knowledge of the fact that there are, of course, long-standing debates in the social sciences about objectivity and the role value judgments play and, more importantly, about whether or not value-laden research is possible and even desirable. In his widely cited essay “‘Objectivity’ in Social Science and Social Policy,” Max Weber argued that the idea of an “aperspectival” social science was meaningless (Weber 1904a [1949]).

Nevertheless, in the spirit of compromise, I would argue that we are well served when we can simultaneously reflect on how our personal experiences/feelings connect to a problem we are trying to understand, even as we aspire to think about those problems critically. The ethic that guides us here should be to cultivate a degree of professional detachment from what we are studying, while also acknowledging our biases. Trust me when I say this – it’s hard. And that’s okay.

Political Thinking vs. Critical Thinking

With the advent of 24-hour cable news, young and old alike have become enthralled by the theatrical banter of entertainment news media, which thrives on conflict and encourages demagoguery as part of the process of discussing important social issues.

Political thinking, such as what we often see featured in our MSM (mainstream news media) can contribute to the cultivation of a closed mindset; one that is rigid, dogmatic, defensive, and most of all not critical (to be sure, there is plenty of criticizing – but that’s different from how I am using the term “critical”).

This process of relying on entertainment media to become “informed” has proven to be deeply satisfying for many people. Politics, is in many respects, a performance that is experienced like a “television show.” People have their favorite characters, as political news is both rendered and experienced like a “story.” That it sometimes “informs” is merely tangential to the process.

Some experts have speculated that our media have become addictive. This is because political parties and our MSM all traffic in audience-tested (focus group) simple frameworks – sound bytes – that operate like intellectual short-cuts. They encourage simple solutions to complex problems that help give people a feeling of control that is connected to a deeply held desire/belief that they understand everything. And so it follows, people don’t have to think very hard. And guess what – that’s attractive to many people!

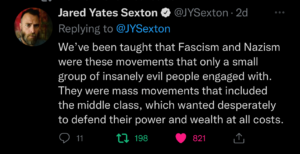

A perfect example of this is when a person accepts a political party’s full roster of beliefs, which is often coupled with a tendency to defend all of its policy positions. This is not at all unlike being a sports fan and rooting for a sports team. The ongoing contest between the Democrats and Republicans is in many ways similar to the Steelers and Ravens rivalry. Such thinking, oddly enough, shares common elements with religious belief (see Durkheim below). Again, you don’t have to think very hard about the issues. Rather, you simply need to identify with and support your team.

Not surprisingly, individuals who desire political affinity are attracted to people who hold their same views. As long as they stay within the confines of their social group, their views won’t be challenged, they can feel like they are “in the know,” and they almost always “get to be right.”

Identity confirming behavior like this further generates strong feelings of belonging, which may, in some instances, constitute a vital aspect of a person’s self-concept. In this instance, confirming social identity is more important than exercising rationally informed, independent, critical thinking! Mind blown!

The powers of affinity that drive identity politics are powerful precisely because they enable individuals to solidify their social group membership when they identify with issues and problems in conforming ways that mirror party-line thinking. The attraction here – and I can’t emphasize this enough – is that political thinking helps people to not feel alone; in sacrificing their independence to the group, they relieve themselves of the burden of thinking on their own.

One interesting issue that I want to call attention to is the case where people are forced to confront information that they cannot reconcile with their deeply-held political beliefs. This conflict is identified by psychologists, who study it, by the term cognitive dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance usually involves feelings of discomfort that most of us would prefer to avoid. In order to reconcile the mental discomfort and to restore balance, people with strong political beliefs may actively resist and dismiss critical facts and information that conflict with their cultivated worldview.

Critical Thinking in the Social Sciences

C. Wright Mills & the Sociological Imagination

The American sociologist, C. Wright Mills, coined the term the “Sociological Imagination” in his 1959 book of the same title to describe a type of critical insight that could be offered by the discipline of sociology. The term itself is often used in introductory sociology textbooks to explain how sociology might help people cultivate a “habit of mind” with relevance to daily life; it stresses that individual problems are often rooted in problems stemming from aspects of society itself.

Mills intended the concept of the sociological imagination to describe “the awareness of the relationship between personal experience and the wider society.” More specifically, he intended the concept to help people distinguish “personal troubles” and “public issues.” To this end, an individual might use this cultivated awareness to “think himself away” from the familiar routines of daily life. We will use this concept in our work together to critically think about social issues and problems.

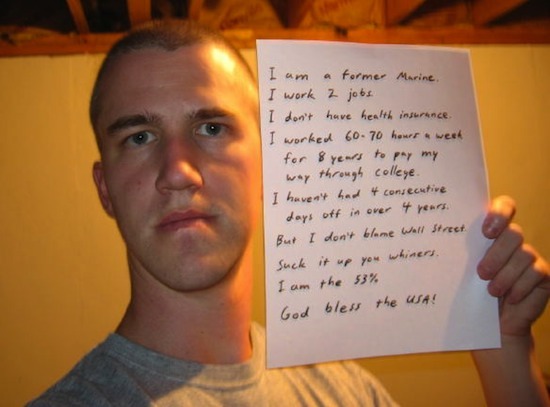

Personal troubles are problems that affect individuals, where other members of society typically lay blame for lack of success on the individual’s own personal and moral failings. Examples of this include things like unemployment/job loss, eating disorders/overweight, divorce, drug problems.

Public issues find their source in the social structure and culture of a society; they are problems that affect many people. Mills believed it is often the case that problems considered private troubles are perhaps better understood to be public issues.

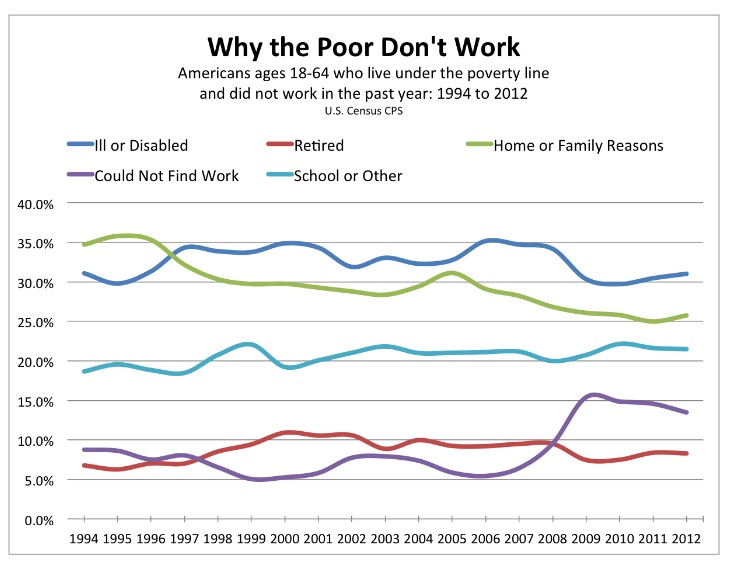

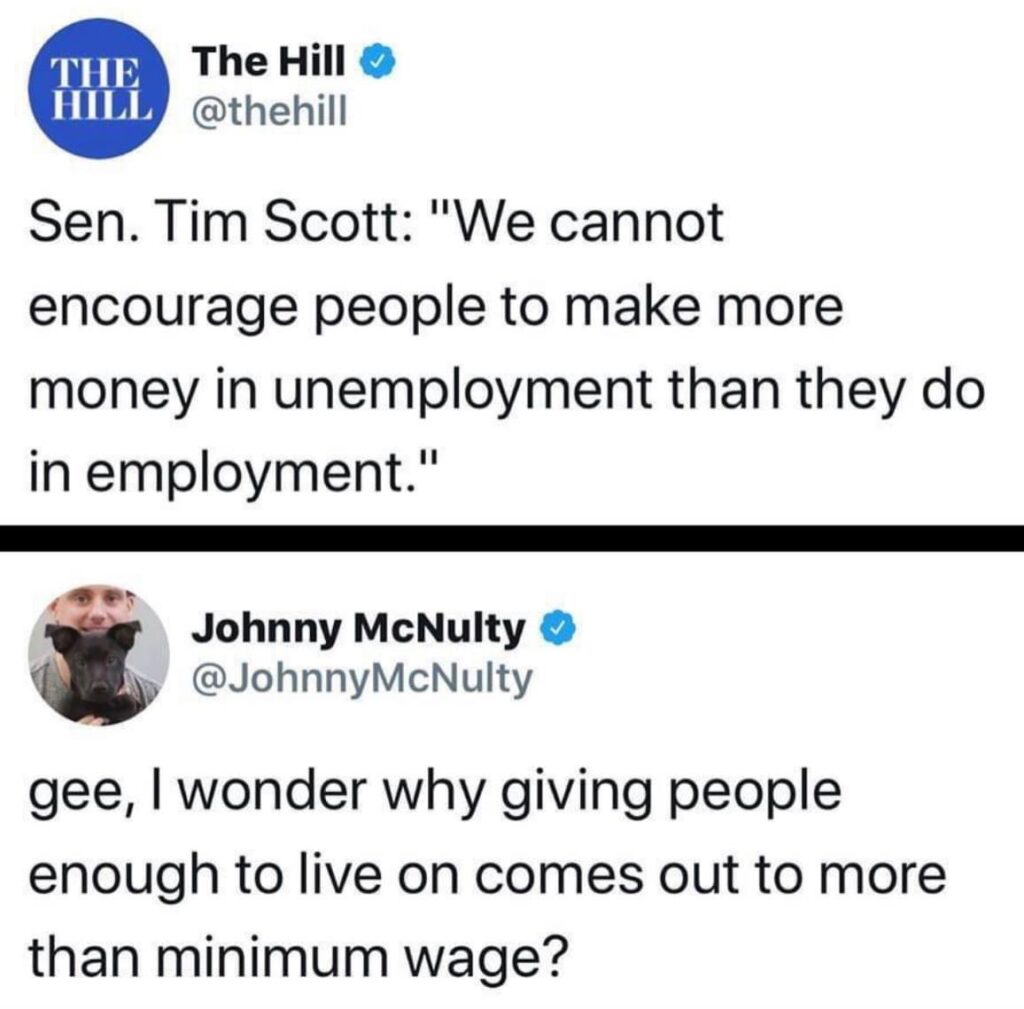

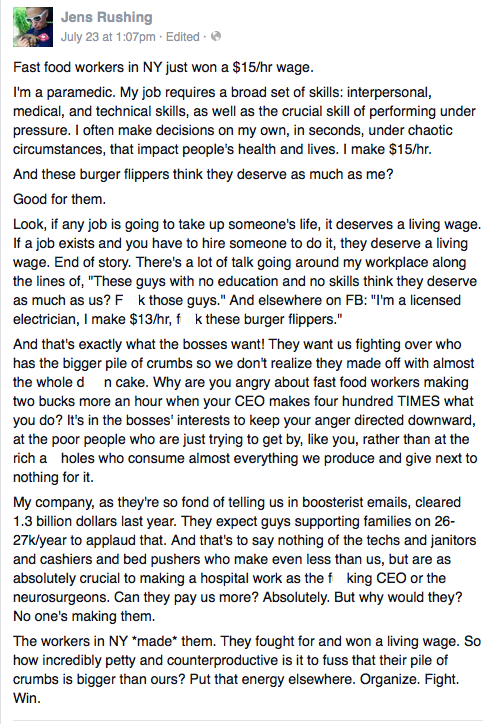

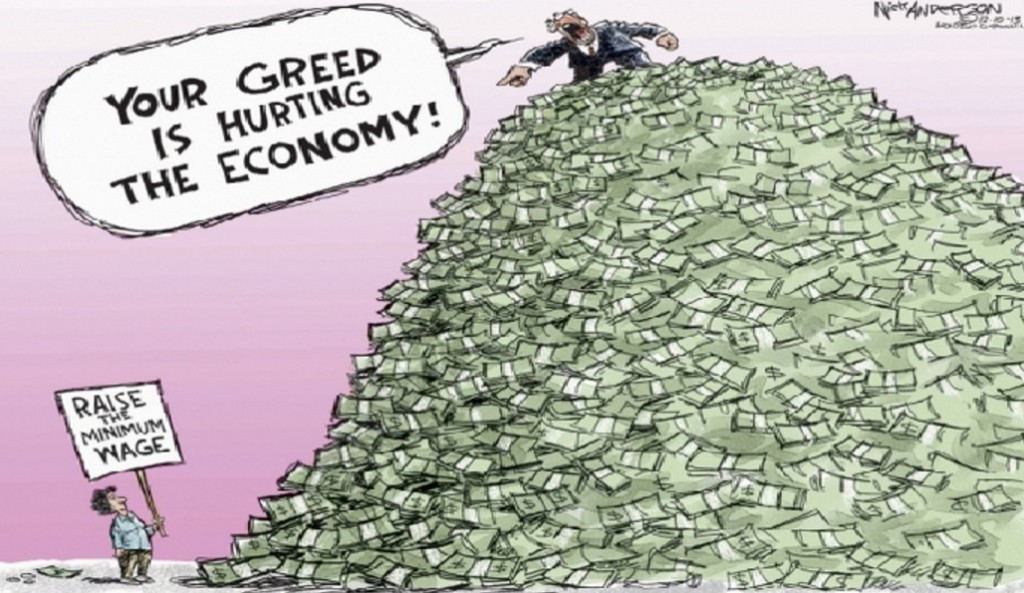

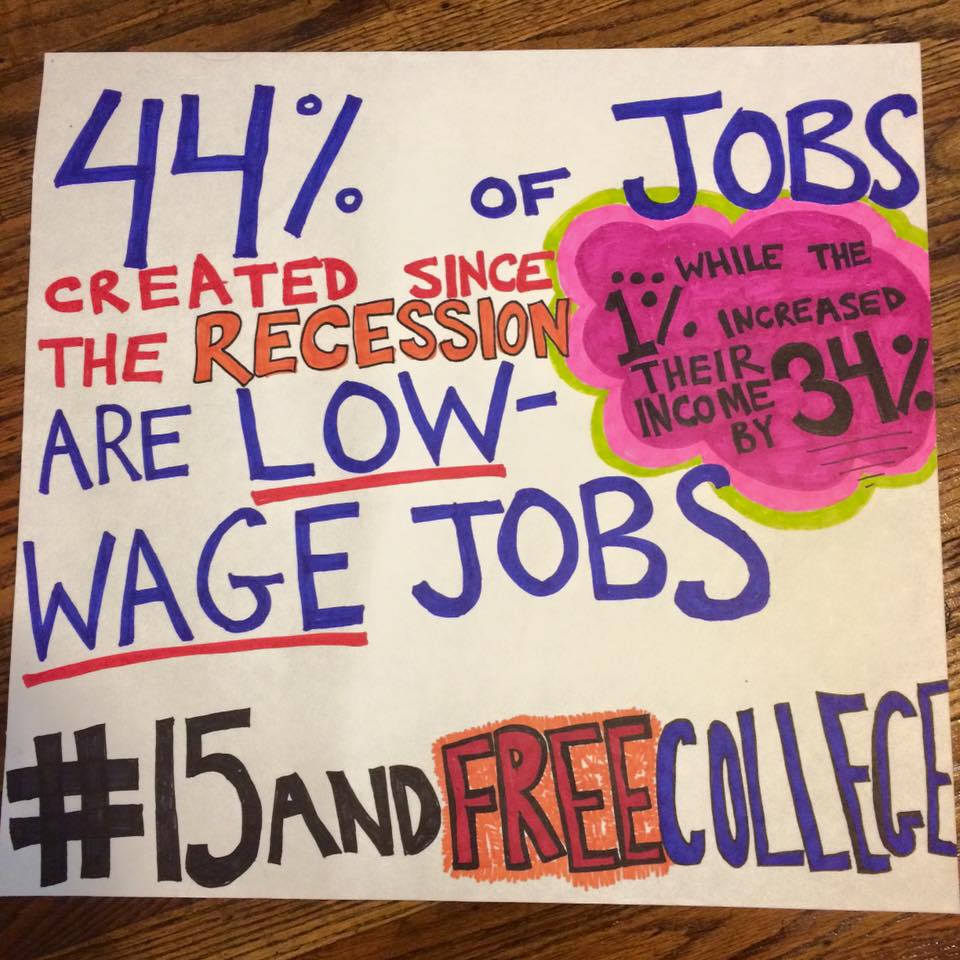

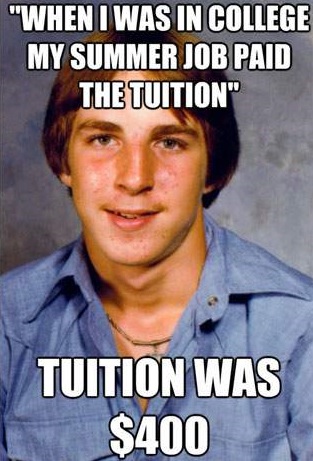

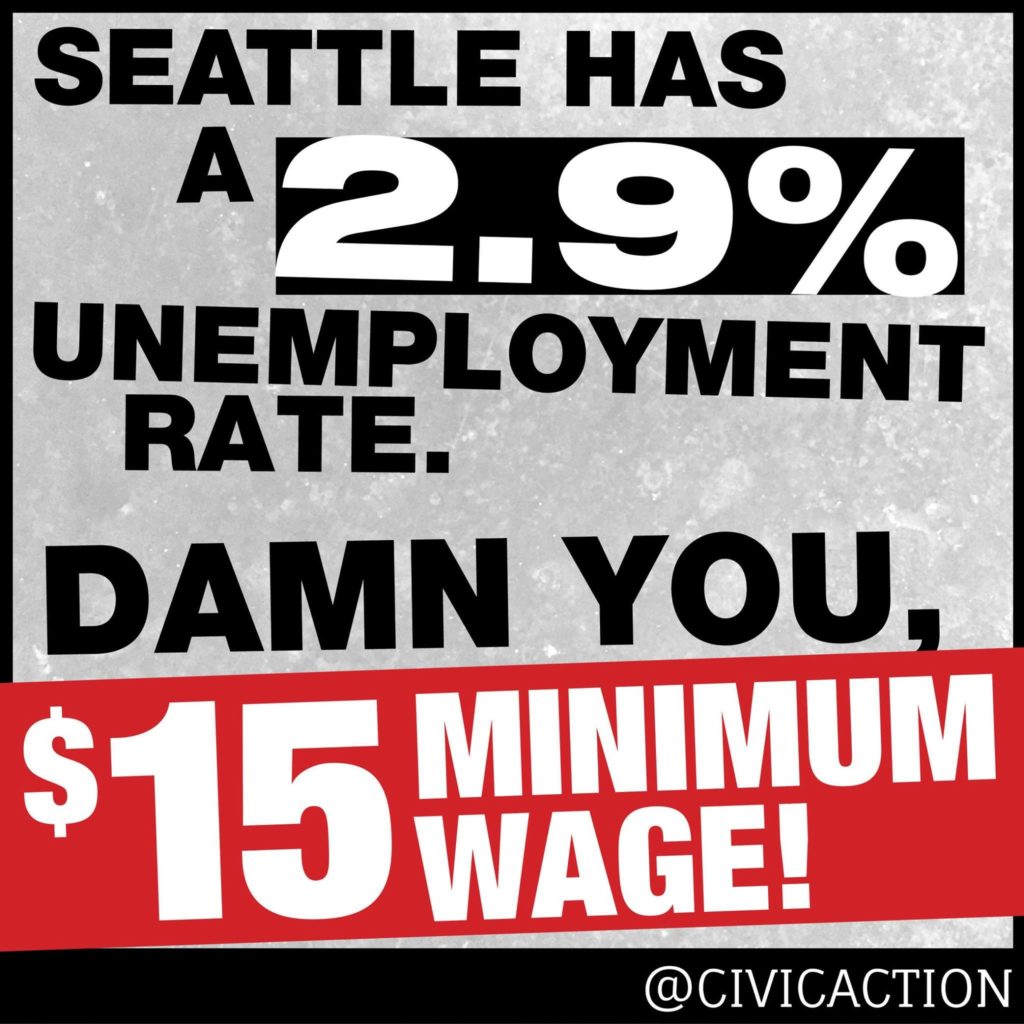

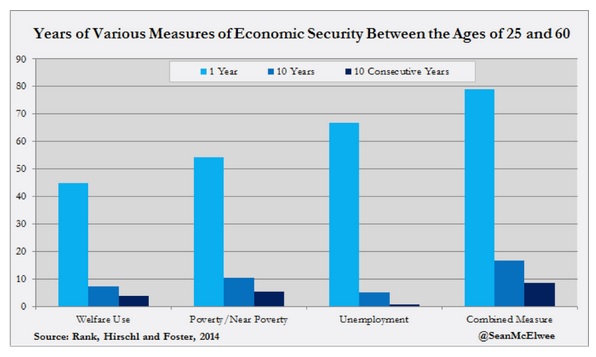

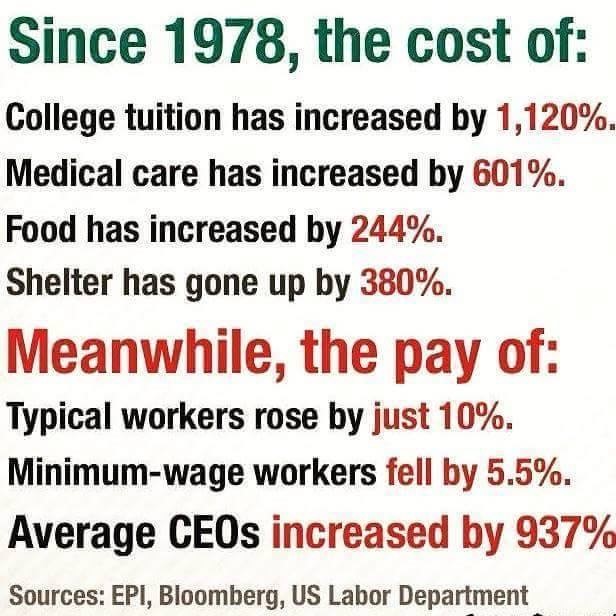

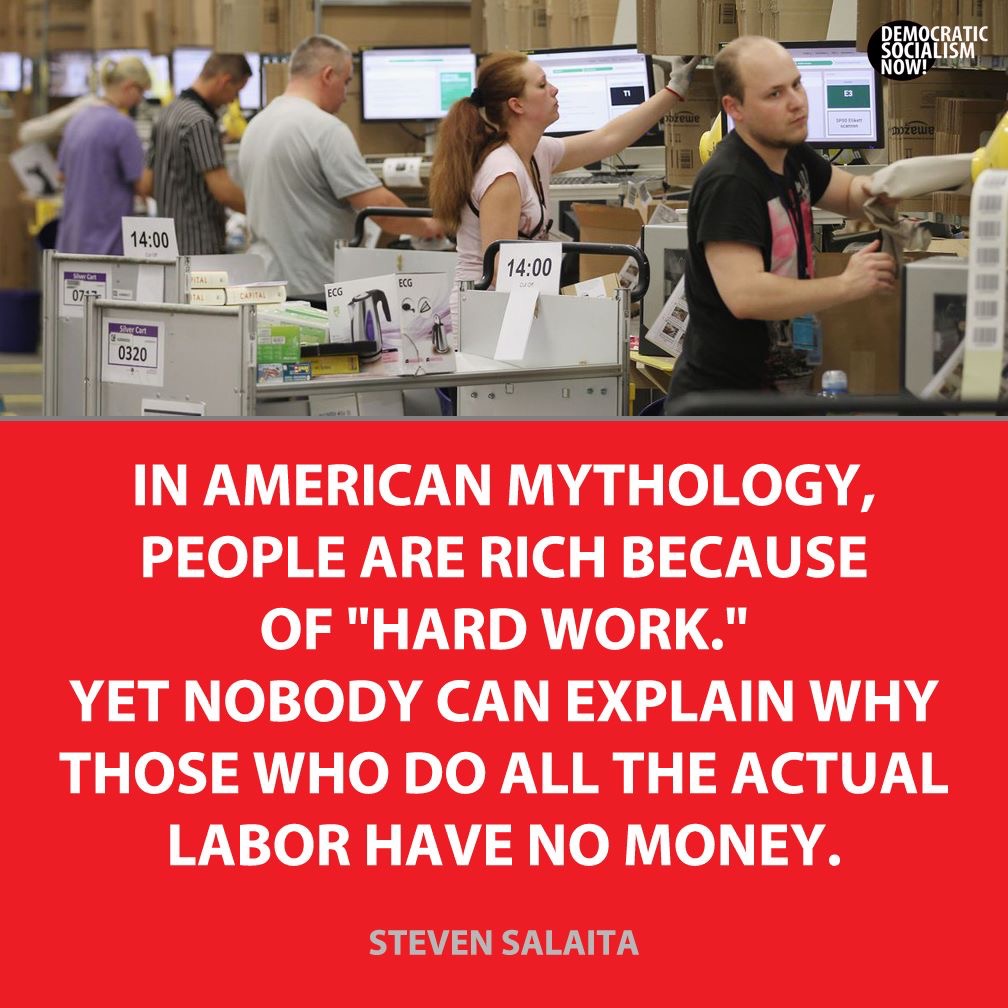

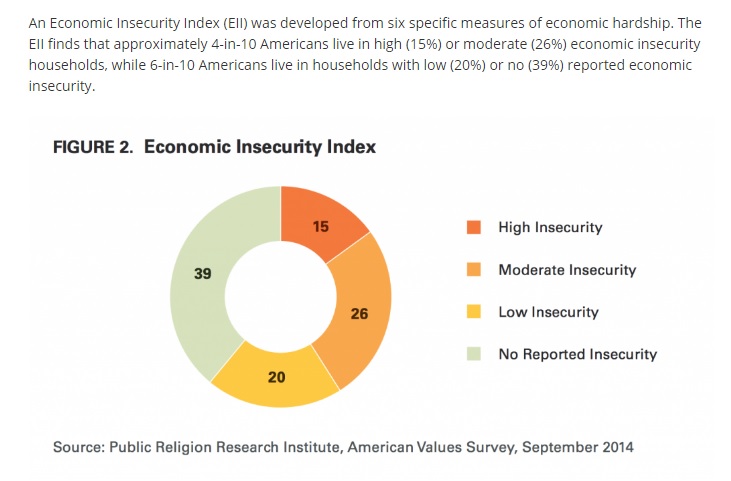

Let’s take Mills example of unemployment. If it were the case that only a couple of people were unemployed, we could then perhaps explain their unemployment by saying they were lazy, lacked good work habits, etc. That is to say, their unemployment would be their “personal trouble.” To be sure, there are some unemployed individuals who are no doubt lazy and/or lack good work habits. Notwithstanding, when we find millions of people are out of work, unemployment is better understood as a public issue. Which is to say, a structural explanation that looks at the lack of opportunity in connection with the economy is better suited to explain why so many people might be out of work. (Mills, 1959, p. 9).

By following Mills and developing a sociological imagination, people might develop a deep understanding of how one’s personal biography is the result of a historical process. Everyday experiences are connected to a larger social context.

Individual vs. the Social (Agency vs. Structure)

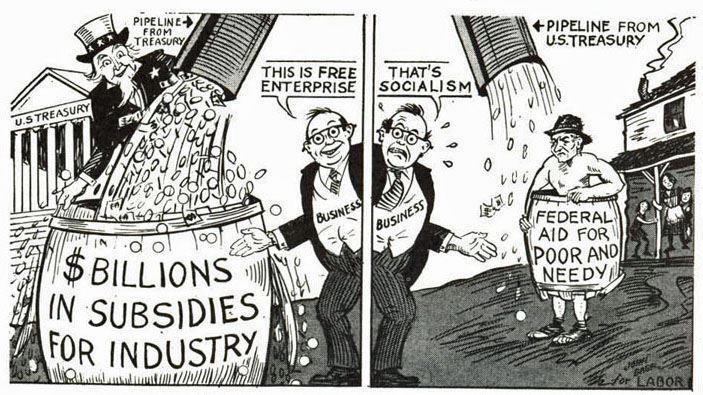

The root of a given problem, according to Mills, is almost always found in the structure of the society and the changes happening within it. Put another way, Mills is saying that many of the problems individuals confront in society have social roots. Moreover, the problems that people assume are theirs and theirs alone are, in reality, shared by many other people. This is why sociologists spend so much time trying to illustrate the sociological roots of problems, because it helps people to understand how their biography is linked to the structure and history of society.

So why do we bother with all of this? Well, for some of us (researchers included), it is because we want to empower individuals to transcend their day-to-day personal troubles, to see how they are public issues and in the process help facilitate social change.

Let’s look at a practical illustration. Take, for example, a person who can’t find a job, pay the mortgage, pay the rent, etc. These are problems that are typically (and sadly) often seen to be the result of a personal failing or weakness. The individual is thought to be the cause of their own problem due to some failure or error.

In the same manner, unemployment can be an extremely negative private experience. Feelings of personal failure are common when one loses a job. Unfortunately, when the employment rate climbs (any number about 6 percent is considered high in the United States) people often see it as the exclusive result of a character flaw or weakness, not the result of larger and more overwhelming structural forces.

Now, for the record, Mills is not arguing that individuals are never responsible for some of their own problems – that they don’t have the ability to make choices, even bad ones, or that they that they have no personal responsibility for their actions. It’s just that many of their decisions don’t occur in a void. They are socially structured.

The same holds true for people who commit crime. Rather than focusing only on individual pathology alone, we should also look at the social and political context within which crime occurs. That is, we need to look at the role that structure plays in determining who commits a crime and who becomes a victim of crime.

Mills would ask: is there is something within the structure of society that is contributing to the problem?

As it turns out, the answer is often YES! In many countries today, unemployment may be explained by the public issue of economic downturn (deindustrialization), caused by industry failures (mortgage, banking, manufacturing). In other words, the problem is social and institutional – not simply the result of the personal shortcomings of one person or a group of people not working hard.

Again, this is why it is important to distinguish that Mills is not saying people shouldn’t work hard. The sociological imagination should not be used as an excuse for an individual to not try harder to achieve success in life, or for people to not claim some measure of personal responsibility for their problems.

Rather, what Mills is saying is that in many situations a person may fail even if they try to do everything right, work hard, go to school, get a job, etc.

When it appears that many people or social groups in society lack the ability to achieve success, instead of being quick to assign blame, Mills says we should dive in and identify the roots of the structure, such as inefficient political solutions, the racial, ethnic, and class-based discrimination of groups, and the exploitation of labor forces.

We should all be reminded that there are problems that cannot be solved by individuals alone (by individuals working harder).

In light of this, it is important that we use our sociological imagination and apply it in our daily lives, this way we might be able to change our personal situation and in the process create a better society.

Emile Durkheim (note: this passage about Durkheim is reblogged here from an article by Galen Watts sourced below)

Globally, we are currently experiencing tremendous social and political turbulence. At the institutional level, liberal democracy faces the threat of rising authoritarianism and far-right extremism. At the local level, we seem to be living in an ever-increasing age of anxiety, engendered by precarious economic conditions and the gradual erosion of shared social norms. How might we navigate these difficult and disorienting times?

Emile Durkheim, one of the pioneers of the discipline of sociology, died just 101 years ago this month. Although few outside of social science departments know his name, his intellectual legacy has been integral to shaping modern thought about society. His work may provide us with some assistance in diagnosing the perennial problems associated with modernity.

Whenever commentators argue that a social problem is “structural” in nature, they are invoking Durkheim’s ideas. It was Durkheim who introduced the idea that society is composed not simply of a collection of individuals, but also social and cultural structures that impose themselves upon, and even shape, individual action and thought. In his book The Rules of the Sociological Method, he called these “social facts.”

A famous example of a social fact is found in Durkheim’s study, Suicide. In this book, Durkheim argues that the suicide rate of a country is not random, but rather reflects the degree of social cohesion within that society. He famously compares the suicide rate in Protestant and Catholic countries, concluding that the suicide rate in Protestant countries is higher because Protestantism encourages rugged individualism, while Catholicism fosters a form of collectivism.

What was so innovative about this theory is that it challenged long-standing assumptions about individual pathologies, which viewed these as mere byproducts of individual psychology.

Adapting this theory to the contemporary era, we can say, according to Durkheim, the rate of suicide or mental illness in modern societies cannot be explained by merely appealing to individual psychology, but must also take into account macro conditions such as a society’s culture and institutions.

In other words, if more and more people feel disconnected and alienated from each other, this reveals something crucial about the nature of society.

The Shift from Premodern to Modern

Born in France in 1858, the son of a rabbi, Durkheim grew up amid profound social change. The Industrial Revolution had drastically altered the social order and the Enlightenment had by this time thrown into doubt many once-taken-for-granted assumptions about human nature and religious (specifically Judeo-Christian) doctrine.

Durkheim foresaw that with the shift from premodern to modern society came, on the one hand, incredible emancipation of individual autonomy and productivity; while on the other, a radical erosion of social ties and rootedness.

An heir of the Enlightenment, Durkheim championed the liberation of individuals from religious dogmas, but he also feared that with their release from tradition individuals would fall into a state of anomie — a condition that is best thought of as “normlessness” — which he believed to be a core pathology of modern life.

For this reason, he spent his entire career trying to identify the bases of social solidarity in modernity; he was obsessed with reconciling the need for individual freedom and the need for community in liberal democracies.

In his mature years, Durkheim found what he believed to be a solution to this intractable problem: religion. But not “religion” as understood in the conventional sense. True to his sociological convictions, Durkheim came to understand religion as another social fact, that is, as a byproduct of social life. In his classic The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, he defined “religion” in the following way:

“A religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden — beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them.”

The Sacred and the Quest for Solidarity

For Durkheim, religion is endemic to social life, because it is a necessary feature of all moral communities. The key term here is sacred. By sacred Durkheim meant something like, unquestionable, taken-for-granted, and binding, or emitting a special aura. Wherever you find the sacred, thought Durkheim, there you have religion.

There is a sense in which this way of thinking has become entirely commonplace. When people describe, say, European soccer fans as religious in their devotion to their home team, they are drawing on a Durkheimian conception of religion. They are signaling the fact that fans of this nature are intensely devoted to their teams — so devoted, we might say, that the team itself, along with its associated symbols, are considered sacred.

We can think of plenty of other contemporary examples: one’s relationship with one’s child or life partner may be sacred, some artists view art itself — or at least the creation of it — as sacred, and environmentalists often champion the sacrality of the natural world.

The sacred is a necessary feature of social life because it is what enables individuals to bond with one another. Through devotion to a particular sacred form, we become tied to one another in a deep and meaningful way.

This is not to say that the sacred is always a good thing. We find the sacred among hate groups, terrorist factions, and revanchist political movements. Nationalism in its many guises always entails a particular conception of the sacred, be it ethnic or civic.

But, at the same time, the sacred lies at the heart of all progressive movements. Just think of the civil rights, feminist and gay liberation movements, all of which sacralized the liberal ideals of human rights and moral equality. Social progress is impossible without a shared conception of the sacred.

Durkheim’s profound insight was that despite the negative risks associated with the sacred, humans cannot live without it. He asserted that a lack of social solidarity within society would not only lead individuals to experience anomie and alienation but might also encourage them to engage in extremist politics. Why? Because extremist politics would satiate their desperate desire to belong.

Thus we can sum up the great dilemma of liberal modernity in the following way: how do we construct a shared conception of the sacred that will bind us together for the common good, without falling prey to the potential for violence and exclusion inherent to the sacred itself?

This question which preoccupied Durkheim throughout his entire life — remains as urgent today as ever before.

~ end blog post

Contrarianism is a Helluva drug – The Devil’s Advocate

Playing the “Devil’s Advocate” (DA) is not a very good way to exercise critical thinking. That is because this particular approach to debate is premised on the idea that every intellectual idea can be explored through a discussion of its opposite.

One tell you will notice is that the DA often advocates for viewpoints that have already been discredited or ones they are not prepared to offer critical evidence to support (…and I might add here, often ones that they personally believe but they are embarrassed to say as much).

This is a Game

The devil who proposes a game of “Devil’s Advocate” in a debate are actively circumventing/undermining critical thinking under the guise of being reasonable; they’re playing a game and the goal of the game is to “win.”

People who play DA are not helping to advance a discussion of a problem or situation. Even though they may profess an interest in political neutrality by evaluating “both sides” of an argument, what they are doing with this pedagogical approach is indulging in binary thinking. Playing game of “point-counterpoint,” the DA aims to limit perspective (confining it to the two poles of the binary) even as they are pretending to open it up. And as it has already been pointed out, real problems that are worth solving are generally more complicated than “two-sides.”

I will concede one point here, however, which is that the Devil’s Advocate (DA) approach can be a legitimate debating tool if it helps integrate a perspective that is not being considered, where the aim is to get someone to consider new information. In this aspect, the DA might help if the goal is to help overcome ideas perceived to be one-sided and biased (Fabello, 2015).

Righteous dude, Elon Musk, hits a blunt with Joe Rogan, while workers in his Tesla plant are subject to drug testing. Like Hegel before him, he is smart but he’s a walking contradiction (no one likes him either). Don’t be Elon.

Where groups of students are concerned, debate games are admittedly a good way to learn about a topic. This approach can help “juice up” classroom dynamics beyond what might be accomplished by a traditional lecture approach, as it gives give students an opportunity to compete, inform, and have fun with each other.

Unfortunately, in real life, when the Devil’s Advocate shows up to argue, it doesn’t work out like this. The debate tends to play itself out and quickly becomes tiring for those relegated to the role of witness.

The Dialectics of the DA

The DA is a master of contradiction. Unfortunately, constant contrarianism does little to foster understanding of a problem. In a classroom it can be downright annoying for those forced to listen on the sidelines.

When the DA joins the debate, their true objective is to provoke conflict. Mistaking antagonism for skepticism and critical inquiry, the DA is often the consummate polished bully.

DA’s like zero-sum combat. Nothing delights them more than dragging a room full of spectators through seemingly endless, fruitless, and circular discussions, which ultimately never serve to help anyone change their point of view.

That’s why this approach cannot be dismissed as only a tiresome debate tactic; it’s far more than that – it’s a malignant thought paradigm that aggressively works to shut down critical thinking.

Reducing problems to two sides – the formula for a classic conflict paradigm – is a Hegelian exercise in futility; it’s designed to wear you out. As a result, you may be tempted to give up on critical thinking and side with the bully in the room if only for reasons of wanting to avoid sheer exhaustion!

The Devil in Disguise

A typical DA positions himself as a well-meaning “honest broker,” who merely wants to provide us with “the other side of the story.” To recap, DA thinking goes something like this: by arguing from an opposite, contrarian perspective, I will contribute a much needed missing perspective and help achieve a new level of understanding.

Efforts are made to signal neutrality when discussing the topic at hand. Convinced of their own earnestness, the DA will often emphasize how they want to intelligently and rationally debate a topic (even if they have zero experience with the said topic). Sounds legit. But hold on. There’s more.

In some instances, a DA may go as far as to politely assert that viewpoints outside of their own are not wrong; they are just uninformed or misguided. No doubt, they are convinced they are flexing their critical thinking muscles when debating this way, as they attempt to wrestle people to the mat to bring them around to accepting their simple truths. Sadly, this debate tactic screams bush-league; it’s high school-level debate. Hint: this is why no one ever likes the devil’s advocate.

In reality, DAs advocate for, and even perform to some extent, a combination of the following:

1) They advocate popular/ conventional “status quo” viewpoints.

2) They advocate polarized “contrarian” thinking.

3) They accuse others who don’t espouse their point of view of being biased.

4) They aim to shut down conversation and discourse – not add to it.

5) They aim to “mainstream” retrograde (out of favor) philosophies.

When I encounter the devil’s advocate, more often than not I find someone who is actively trying to interrupt and, in some cases, dominate my presentation of a problem/idea. But it’s not the fact that they asked me to consider new information that I find to be a problem; it’s their assumption (conceit) that I did not already consider alternative ideas before making my presentation. It’s as if they are telling me they don’t trust my ability to evaluate research and think critically (Fabello, 2015).

Gender & the DA

Shutting down conversation and discourse with debate tactics does not add to learning; it subtracts from learning and that’s oppressive. Nevertheless, the DA is not one who gives up easily.

As is often typical with DAs, sometimes they will go so far as to accuse their debate partner of having a personal bias (even though it never seems to occur to them that they may also be biased). This happens a lot. Sadly, more often than not, it happens with men in particular [even sadder is the fact that men talking down to women remains a common classroom occurrence].

Journalist Melissa Fabello, explains: “men are used to living in a world that affirms and validates their experience as ‘the way things are’ and they are almost never are asked to consider those biases.” When they accuse others of being a victim of their own subjectivity they do so while proclaiming they are, in fact, the one who is demonstrating critical thinking (Fabello, 2015).

What the devil’s advocate offers, more often than not, are feelings and personal opinions stated with confidence, which are disguised as reasoned, conventional, contrarian positions. In a final act of projection, they tend to accuse the very people who are practicing critical thinking of offering personal opinions.

Unable to engage problem-solving based on the actual substance of research and evidence, the DA may resort (when they are at their laziest) to suggesting that the other person’s position or argument be dismissed. In keeping with this, they may go so far as to suggest we consider the radical position that we do nothing at all to solve the problem.

It’s Easy to be a Devil’s Advocate

To put it simply, a DA is a performance artist; one who puts a lot of effort into telling people they are wrong. They are so obsessed with being rational, that they consistently mistake their own feelings for objective logic, on the basis that simply believing in rationality makes their feelings magically rational; thus, their logic system remains a closed circle – and they always get to be right!

Keep in mind that it’s easy to play the role of the Devil’s Advocate. It’s easy to be a contrarian and say “let’s go to opposite land and look at the opposite of what you proposed.” You know what’s hard? Solving a problem. It’s far more difficult to say “yes, we may not be doing it right, so let’s try to think through some different approaches that will allow us to think about this problem from different perspectives and maybe do something new.”

Just to be clear, I want to state for the record that debate and dissent are useful, valuable, and indispensable to the pursuit of knowledge; dissent can help sharpen and sculpt our efforts to achieve knowledge and understanding. Unfortunately, many DA-type contrarians are not interested in these things.

Understanding different points of view, respecting people for those views, and still having the courage to advance your views based on evidence is the goal of rationally informed critical inquiry. The best of us study for years in order to learn about the efforts and approaches others have tried in the service of solving problems. Standing on the shoulders of giants, we look for ways to make a contribution to the research – that means we must do some heavy lifting first, where we evaluate the best ideas and research methods and subsequently devise a new plan to move the research forward. Success here is often achieved in small increments.

In the end, we may or may not make a significant contribution. But we try. Even if we are only one step closer to solving a problem that’s still something to be proud of. The point is that thinking critically about the different steps in the process, collecting the best data and evidence, and even revising our approach along the way is more important than winning a debate or scoring points in the court of public opinion.

Remember that knowledge isn’t a one-way street. The more you treat knowledge acquisition as a competition, the more annoying you’re going to be as a person. You’ll find you won’t gain more wisdom,. You won’t influence anyone with your ideas…and you probably won’t make any friends.

Being smart isn’t about gamesmanship and proving someone wrong; sometimes it’s about fostering agreement through disagreement while getting someone to see your side of it. Wisdom is ultimately less about pride and being correct and more about having empathy and building bridges to knowledge.

What is the Solution?

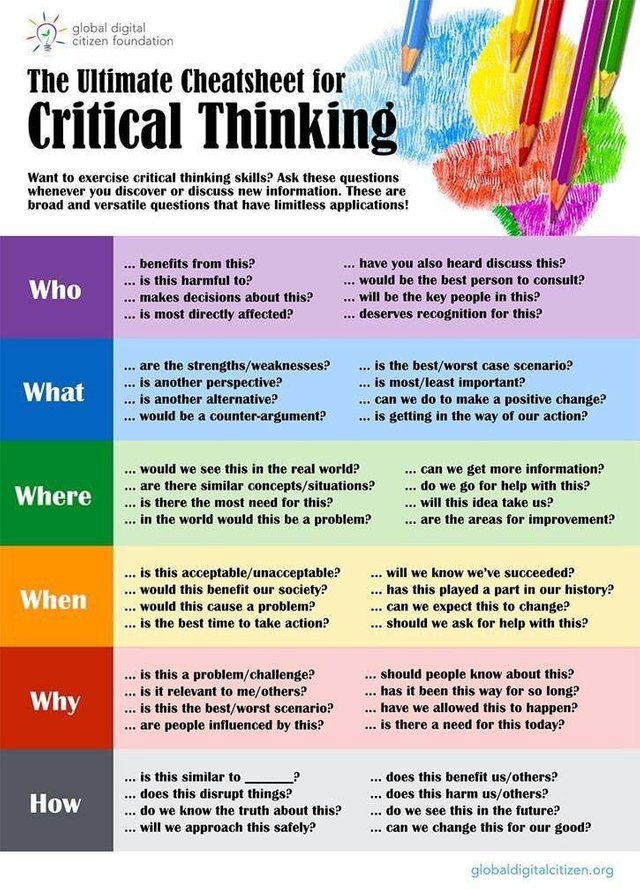

There are no simple answers. We must begin the process of rational inquiry by putting the problem in the center of our efforts to solve problems. By taking ourselves out of the equation and attempting to begin from neutral ground (some people argue all research is ME-search), we might then set about the task of asking a critically informed question.

At this point, assuming there is intellectual curiosity, I hope we can move forward together to discover:

1) what experts have to say about problems; and

2) conceive of a plan (a research design) that can support the gathering of new data to advance understanding and suggest a solution to the problem.

Rinse and repeat as necessary.

Case Dismissed

It cannot be emphasized enough that this debating strategy is not driven by a desire to engage in rational inquiry to advance discourse and knowledge, even if it appears to do that. At its best, it’s an amusing parlor game. At its worst, it betrays an indication of disrespect.

Summary

Critical thinking is more than a “buzz” term. It’s incredibly essential to one’s ability to exercise sound decision-making and function in modern complex societies. The pitfalls and barriers to critical thinking that were discussed here are important to distinguish because they are not only incredibly common, they are important as structures that govern how people understand the world around them – how they interpret their feelings and achieve agreement reality about important social issues and problems. The thought paradigms that were discussed here are essential to how people develop logic systems and whether or not they can think; they have a profound impact on shaping everything that you know and what you think may be possible to know.

Finally, don’t avoid dissent. Don’t always seek out people who agree with you. Try to prove yourself wrong. Disagree. Debate. Admit mistakes. But be respectful. Carve out time and space to consciously reflect. And never forget – if you are the smartest person in the room, you are in the wrong room!

Sources

“Pioneering Sociologist Foresaw Our Current Chaos 100 Years Ago,” by Galen Watts, 2018.

4 Things Men are Really Doing When They “Play Devil’s Advocate” by Melissa Fabello, 2015.

“Why We Should All Stop Saying ‘I Know Exactly How You Feel,’ “ by Celeste Headlee, 2017.

“Stop Saying ‘I Feel Like’ “ by Molly Worthen, 2016.

“Max Weber and Objectivity in Social Science”

“This Week Should Put the Nail in the Coffin for Both Sides Journalism,” by Margaret Sullivan, 2017.

Discussion

What do you do when you have a certain understanding of what you know as Truth and others do not?

What do you do when others are operating under a belief system gained from what others have told them instead of basing their understanding on the knowledge of experts and/or research? Do you challenge them? Or do you “agree to disagree?” [Hint: do not concern yourself if others believe differently. Model what you are coming to know by means of accessing good sources of knowledge and information.]

When you were in high school did you feel prepared to take your exams? Did you do well on your exams? If you did not do well, how did this impact your interest in higher education and your assessment of whether or not you were “smart enough” to do well when you enrolled in college?

How comfortable are you when it comes to discussing sensitive topics in the classroom? Do you ever feel intimidated by professors or classmates?

What would it take for you to feel more comfortable engaging in “difficult” types of conversations?