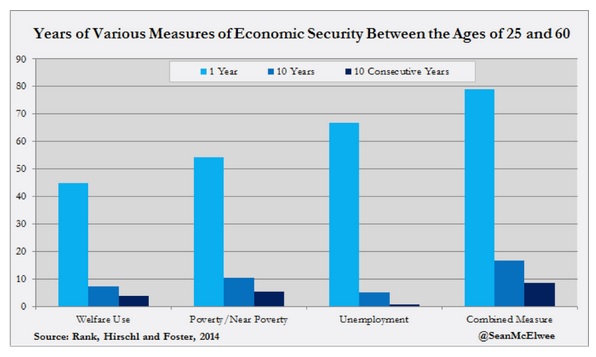

Where to begin? Yes, these countries are broken beyond belief. To begin, they all have a huge homeless population. People are forced to work for such low wages that those wages must be supplemented by government welfare programs (food supplement programs). The medical care system is a byzantine patchwork system that leaves people begging for donations so they can get lifesaving care and/or avoid bankruptcy.

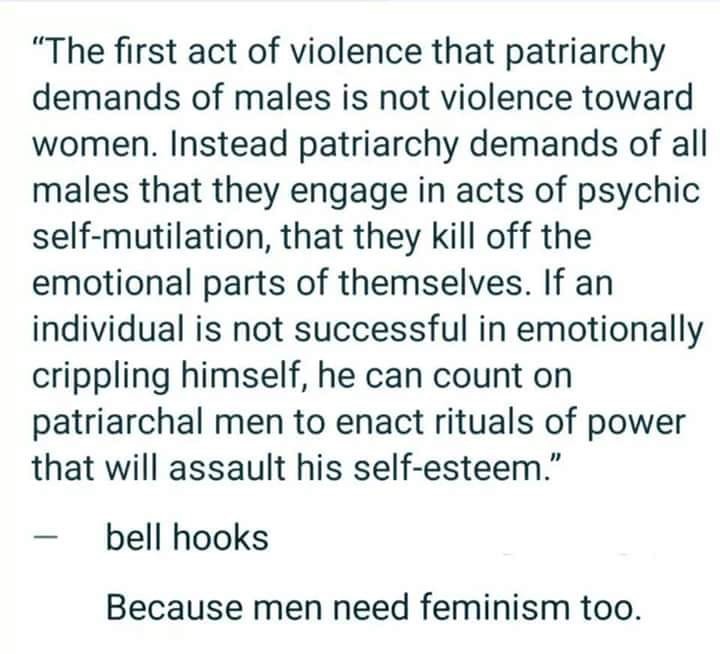

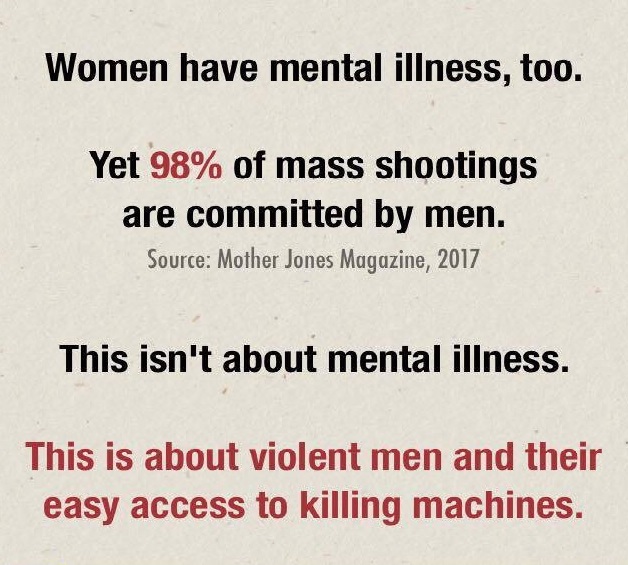

Insurance companies routinely deny care, even though people pay the insurance companies to cover them in times of need. Only the wealthy can really afford to go to college. Many students are forced to take out predatory student loans, the balances of which rival mortgage payments that will follow them for their lifetimes. In this type of system, school teachers are typically poorly paid. It is not uncommon to find college-educated people reduced to living in tents and cars because they can’t afford to rent or own a home. They have children going to bed hungry and the schools take trays of food from them in school because they can’t pay for it. What remains of the chronically underfunded public school system is slowly being turned into private religious indoctrination. Young school children are often shot in their classrooms and thus they don’t live to see their parents again.

Public roads and public transportation are also a disaster. These systems belong in a third-world country. People work in schools and across industry and government, who aggressively deny science because of what the bible says.

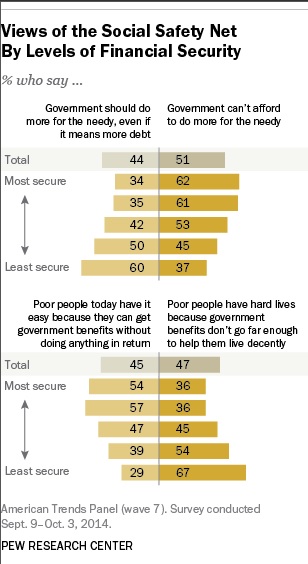

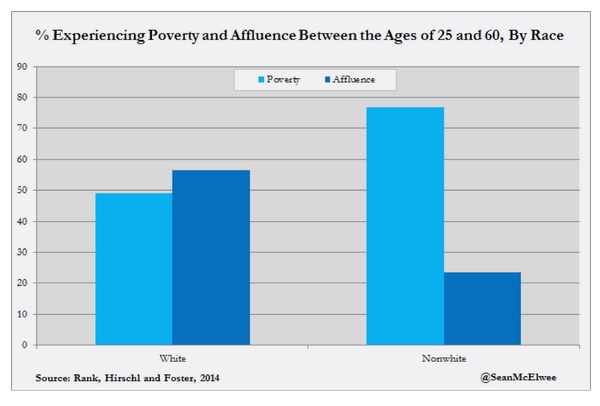

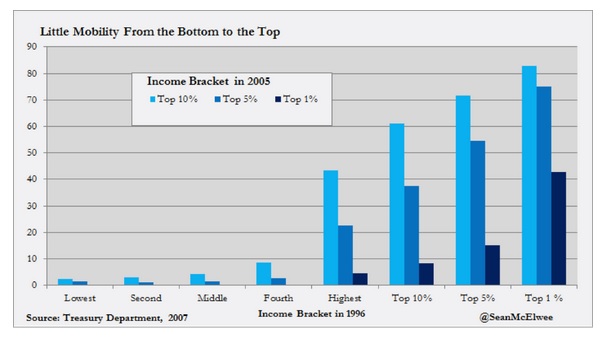

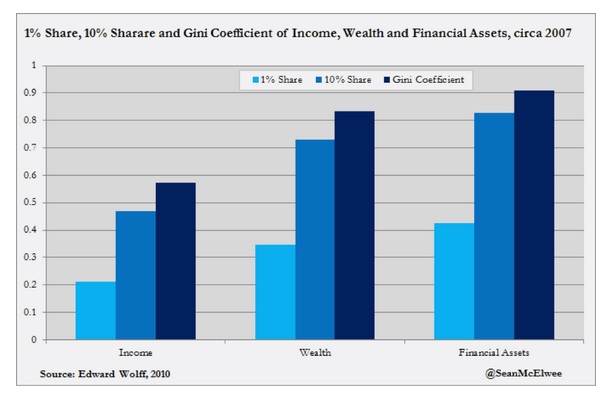

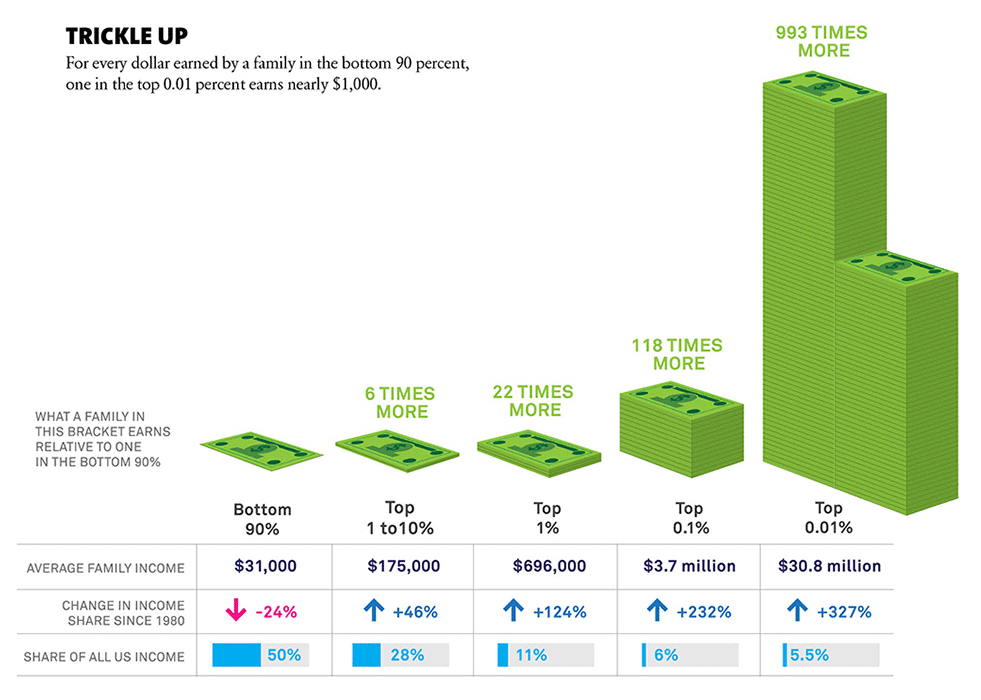

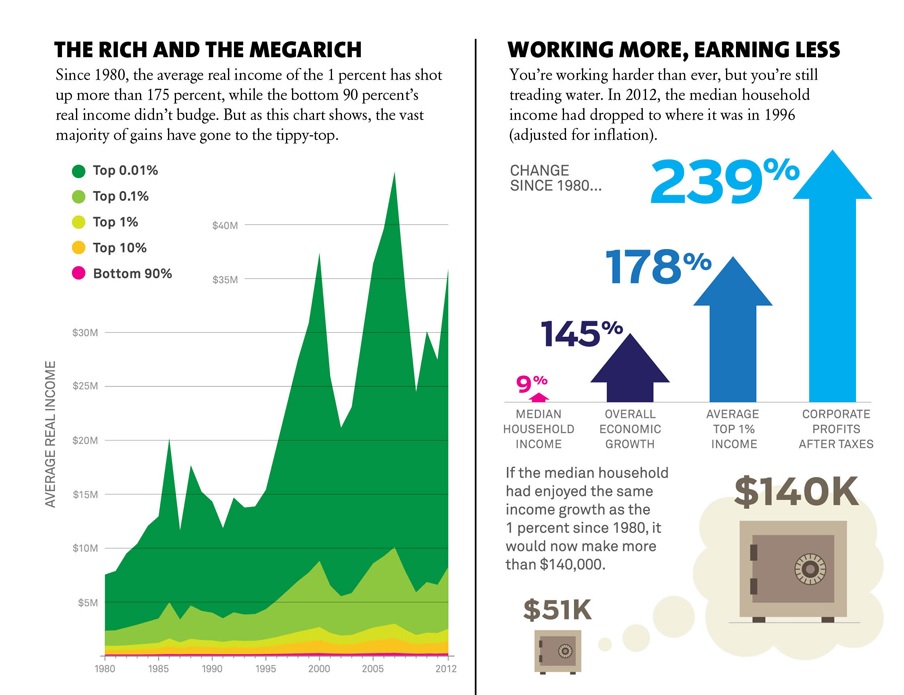

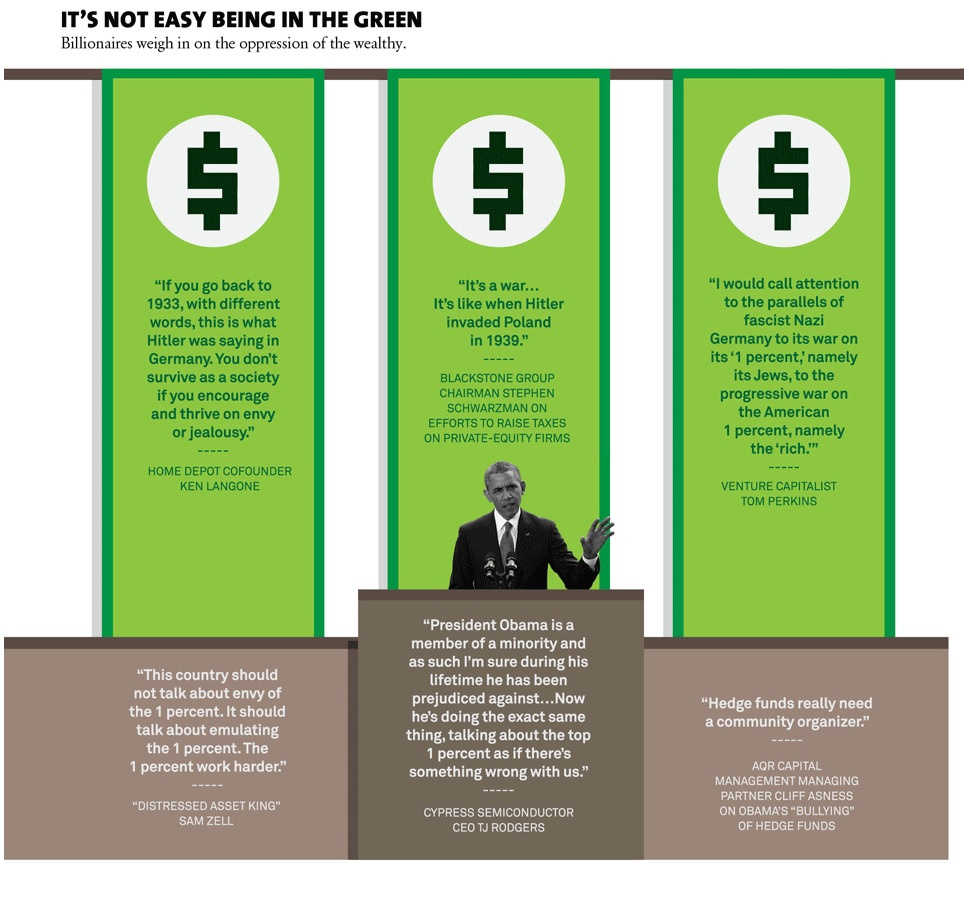

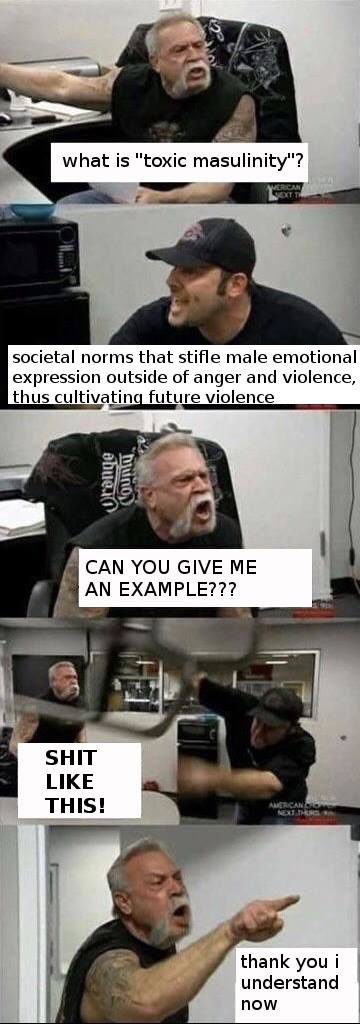

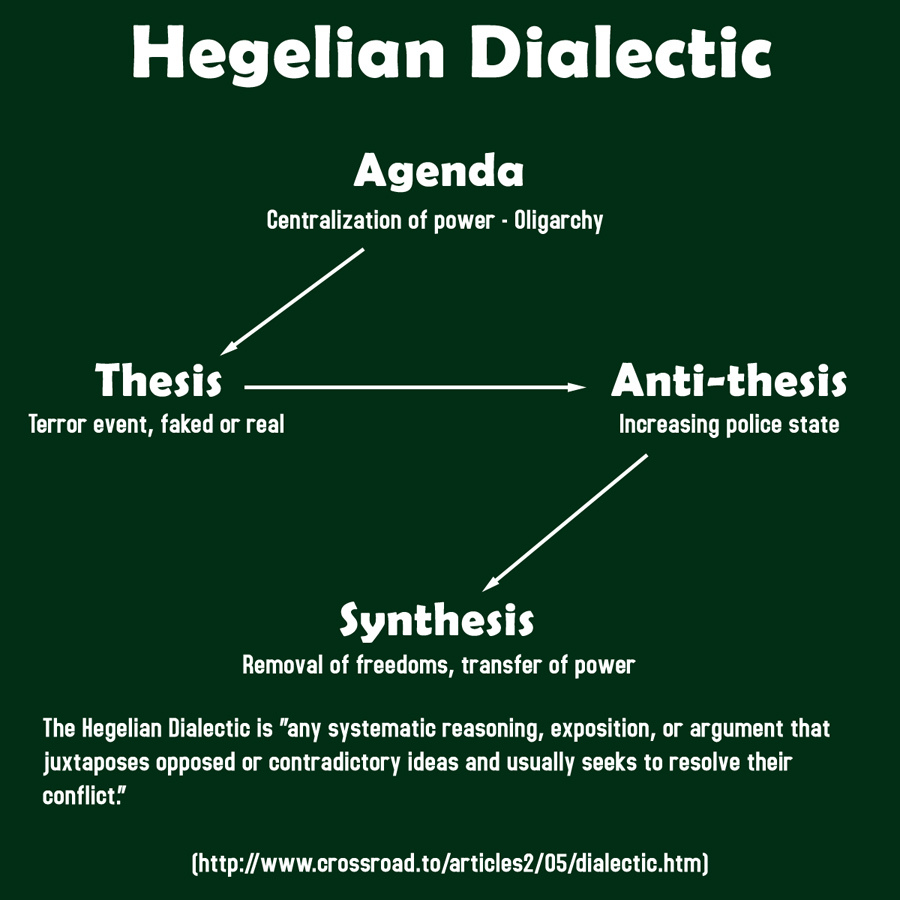

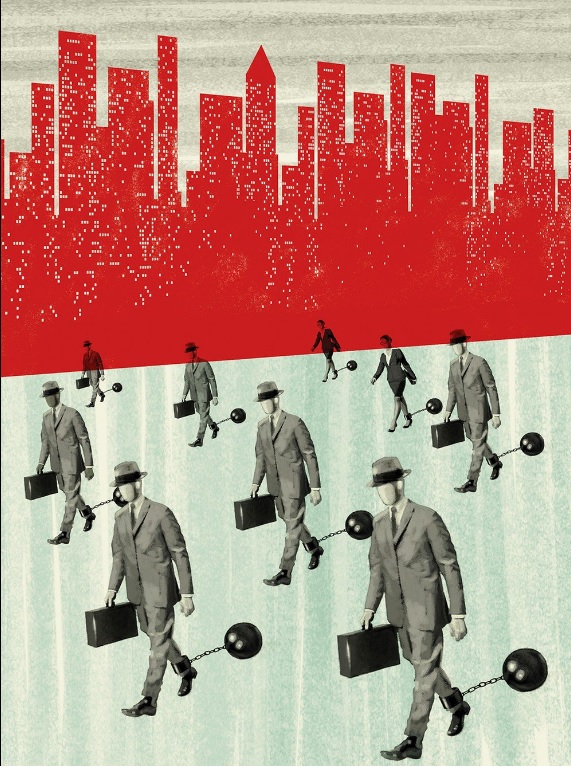

If all of this is not bad enough, they continue to spend millions of taxpayer dollars to fight senseless wars that bomb mostly brown people who are even more disadvantaged into oblivion. This entire system is run by a small group of oligarchic billionaires, who have organized the system to benefit themselves to the detriment of these countries. This makes the general population angry. Consequently, they lash out at anyone and everyone by arming themselves to the teeth such that there are more guns than people.

Oh wait, my bad, This is not how socialist European countries operate; this is how the USA operates.

Most European countries, with a few exceptions, operate mixed market economies with different levels of support for welfare state programs. Most tend to be well-educated and enjoy good health thanks to established universal healthcare programs (or as many in the U.S. like to say “socialist” healthcare). Put another way 32 out of 33 industrialized countries in the world have universal healthcare programs, save the U.S. as the outlier that has chosen to operate a for-profit system dominated by insurance companies. As a result, people don’t die because they can’t afford to pay for things like insulin. In addition, they enjoy open borders, have low crime rates. Perhaps even better, they don’t have mass shootings. In countries that permit gun ownership, those households that own guns must be trained on gun safety and use. Lastly, their homeless rates are low, as are their unemployment rates.

To summarize, people who assume that nations with social safety nets have been destroyed by dreaded “socialism” need to take a hard look in the mirror at their own society. Imagine living in a country where people pay taxes to guarantee access to the important things, while also ensuring that people who need help can get it.

![(Steve Bosch/Vancouver Sun) [PNG Merlin Archive]](http://sandratrappen.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/wealthy-wilmas-1024x866.jpg)