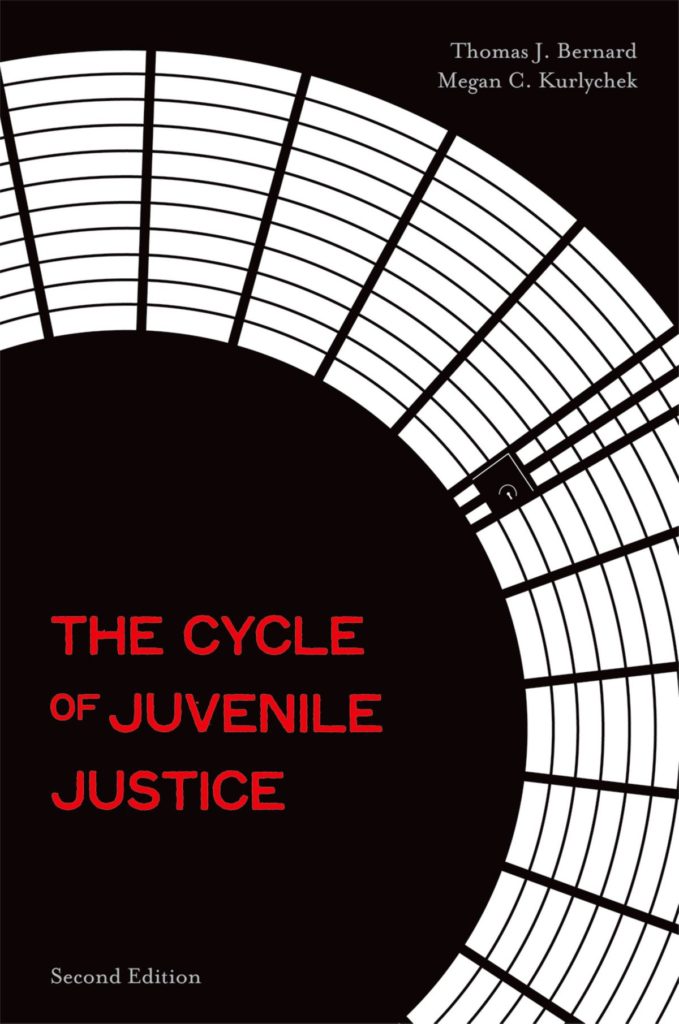

What Goes Around Comes Around

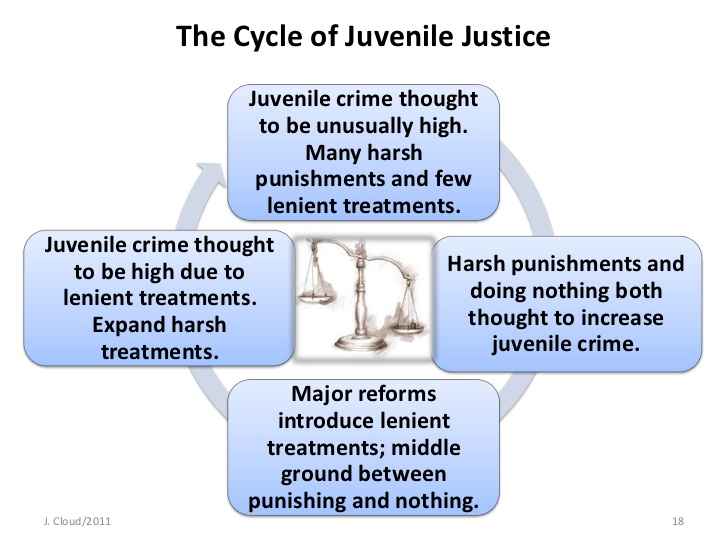

The “Cycle of Juvenile Justice” was first articulated by Thomas Bernard in 1992 and refers to a repetitive historical pattern of juvenile justice incidents and policy responses in the United States. Beginning in the early 1800s, juvenile justice policies alternated between harsh punishment and lenient treatment for juvenile offenders (Bernard & Kurlychek, 2010).

The cycle, according to Bernard, is at all points driven by factors that are described as historical constants: 1) the widespread belief that juvenile crime is at an all‐time high and getting worse; 2) the belief that the juvenile justice system itself is responsible for the high levels of juvenile crime, hence reform of the system will effectively address the problem. Because of these historical constants, it is inevitable that any reform successfully enacted will, in its turn, become perceived as the source of the problem and be scrapped (Bernard & Kurlychek, 2010). .

The cycle begins when the public as well as justice officials arrive at an awareness (belief) that juvenile crime is high and that there are many harsh punishments, but few lenient treatments for offenders. Justice officials are put in a position of making decisions, alternating between harsh, lenient, and sometimes doing nothing at all. This “forced” choice is backed up by a public that believes that variously believes harsh punishments increase juvenile crime and doing nothing increases juvenile crime. What is the solution? Introduce lenient treatments. Everyone feels good that things will get better; that crime rates will decline

(Bernard & Kurlychek, 2010).

But then both the public and justice officials remain convinced that juvenile crime is too high. Now, they blame the lenient treatments, and the pendulum swings in the opposite direction; they believe the only way to fix it is to take a “get tough” approach through the favoring of harsh punishments. Justice officials are again forced to choose between harsh and lenient responses. And so the process continues with the cycle returning to where it started (Bernard & Kurlychek, 2010).

To break it down more simply, there are three major components to the cycle:

- belief that juvenile crime is exceptionally high

- belief that present policies make it worse

- belief that changing policies will reduce juvenile crime

At every step in the process, people believe that their ideas are truly new and will make a difference. This belief cycle, which has existed for the better part of 200 years, drives the system (Bernard & Kurlychek, 2010).

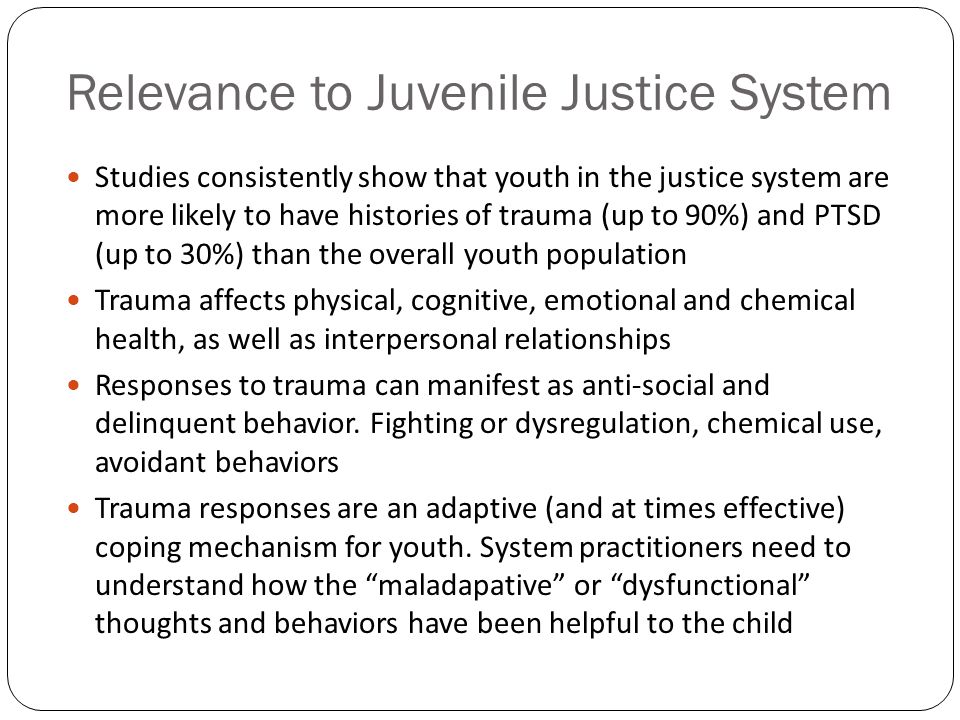

Two other perceptions are also bound up in this system and are revealed to change over time: the idea of juvenile justice and the idea of juvenile delinquency. Note that the two concepts are linked. How you view/understand who is a juvenile exerts a big impact on what you think is the appropriate response by the justice system. For example, do you favor “punishment and deterrence” responses or do you favor reform and rehabilitation approaches? (Bernard & Kurlychek, 2010).

The First Rule of Criminal Justice Thermodynamics

Letting youth off scot-free results in public pressure to reform the juvenile justice system and the cycle repeats (Bernard & Kurlychek, 2010).

Where Are We Now?

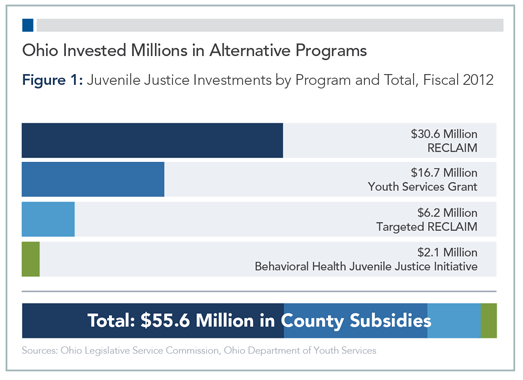

We are currently in a phase that attempting to replace more than a decade of “get tough” policies with more lenient ones. Current policies emphasize behavior modification, counseling, and therapy (Bernard & Kurlychek, 2010).

How Do We Break the Cycle?

Bernard proposes that we study history and that we make an effort to see ourselves as well as our beliefs and policies within a historical context. By looking at the problem from a distance, so to speak, the cycle becomes easier to see and break.

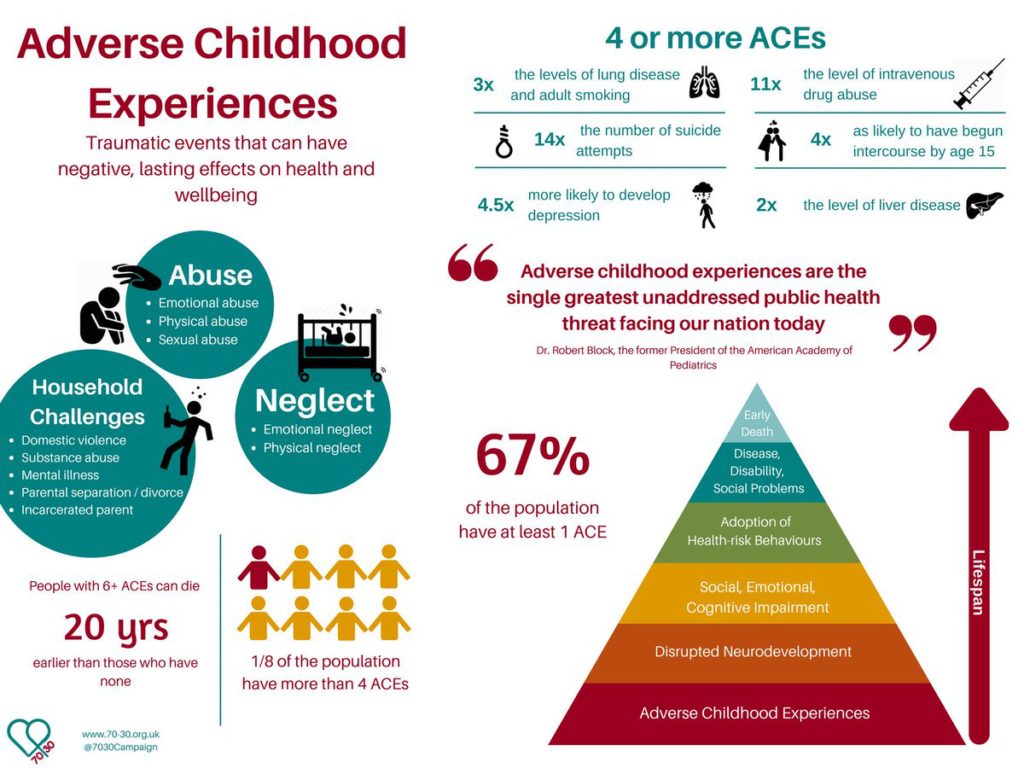

The cycle can only be broken when we realize that there are no “magic bullet” policies that can break the cycle. In other words, we must change our belief that there is some, as of yet, undiscovered policy can influence juvenile crime rates. This is because juvenile crime will always reflect what is happening in the society at large. As such, the ills of any given historical moment will be reflected in the incidents and nature of juvenile crime. To truly change crime you have to reject behaviorist (individualist) approaches and change the root causes that exist in our society – not just the juvenile justice system (Bernard & Kurlychek, 2010).