Inventing the Police

This post takes a “critical” criminological approach to the study of the evolution of modern police forces. Advocating for research-based problem-solving, the aim here is learn about how a data-informed approach, combined with critical interpretive methods, might shed light on the structures of policing and the role it plays historically in the construction of knowledge and power. For it is only by situating policing within this critical social context that we can begin to effectively understand the police.

We begin with some questions: Where does policing originate in the United States? How did policing come into being as the institution that we know today with the oft stated mission of “serve and protect?” How might police act on assumptions about people, particularly as this relates to the way criminals act? How might these assumptions and actions inform public understandings about crime and criminals? What are the actually police doing?

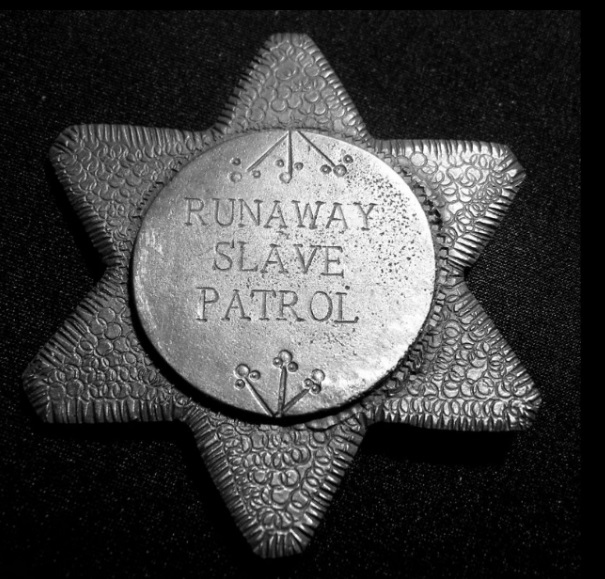

Slave Patrols and The Myth of Liberal Policing

What does modern policing have to do with slave patrols? What exactly is meant by the term “liberal policing?” These are some of the questions that scholar and criminologist, Alex Vitale, addresses in his 2017 book – The End of Policing, which takes a critical look at how modern policing in the United States has evolved over time.

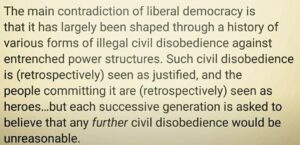

The liberal state, as it were, is not about the classic political divide between democrats (liberals) and republicans (conservatives). What this term refers to is a general notion of statehood – an ideal invested in action – where the state/Justice Department invests in reforms like body cameras, community policing, officer diversity, and increased implicit bias and use of force training as a means to rescue policing and restore its legitimacy. Vitale cautions that while this notion may be superficially appealing, the U.S. falls short of such aspirational ideals in practice. To understand how this occurred, he says we need to take stock of our police history and reconcile where we came from before we move forward.

[Note: the term “liberal state” does not mean liberal in the same sense as it is used by many people to characterize one political party/governing ideology. The term as it used here broadly refers to the state as a form of governance organized to protect and promote the economic and social well-being of citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equitable distribution of wealth, and public responsibility for citizens unable to avail themselves of the minimal provisions for a good life.

Alternatively, “Liberalism” is a political and moral philosophy that espouses the values of liberty and equality. Professed “liberal” democracies espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but they generally support civil rights, democratic ideals, secular government, gender and racial equality, freedom of speech, press, and religion. Liberalism became a distinct movement during the Age of the Enlightenment when it became popular with Western philosophers and economists. Refuting norms of power based on heredity, monarchy, and the divine right of kings, liberalism sought to replace them with traditional conservatism, representative democracy, and rule of law. French liberalism emphasized rejecting authoritarianism linked to nation-building].

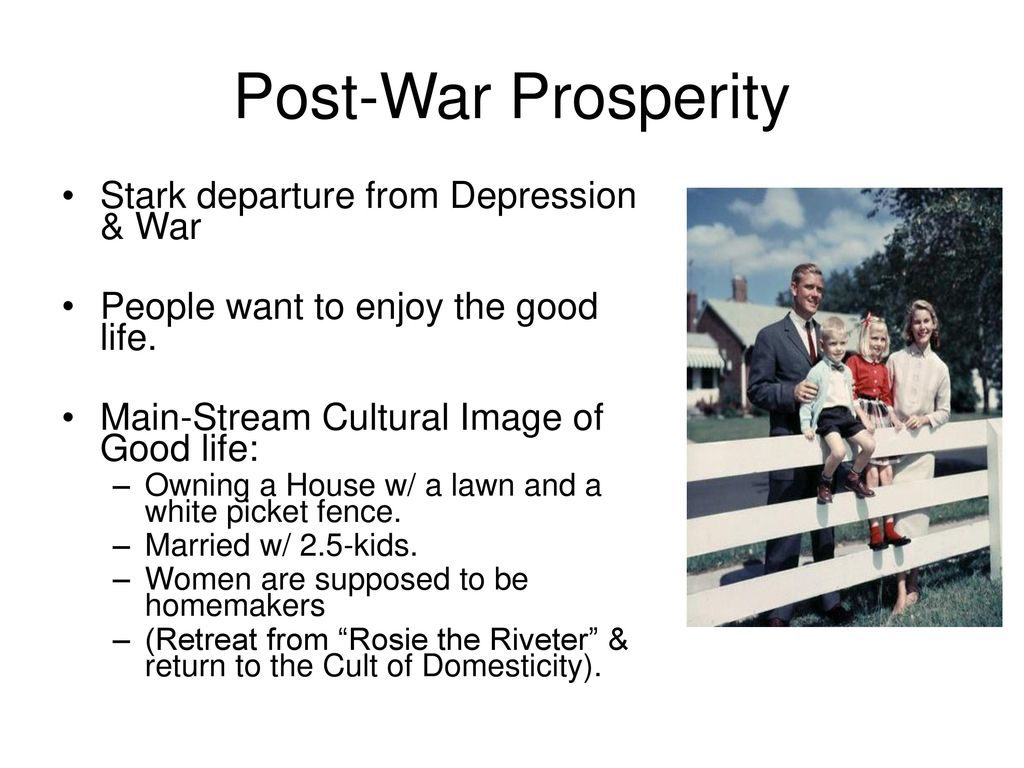

Sociologist T.H. Marshall described the modern liberal welfare state as a distinctive combination of democracy, welfare provision, and capitalism.

A liberal state, furthermore, is one which gives priority to the cause of the individuals. In the classic ‘individual vs state’ opposition, the liberal state is supposed to favor the interest and cause of individuals. Put another way, a classic liberal state refers to limited government or limited state.

Early Policing

The London Model

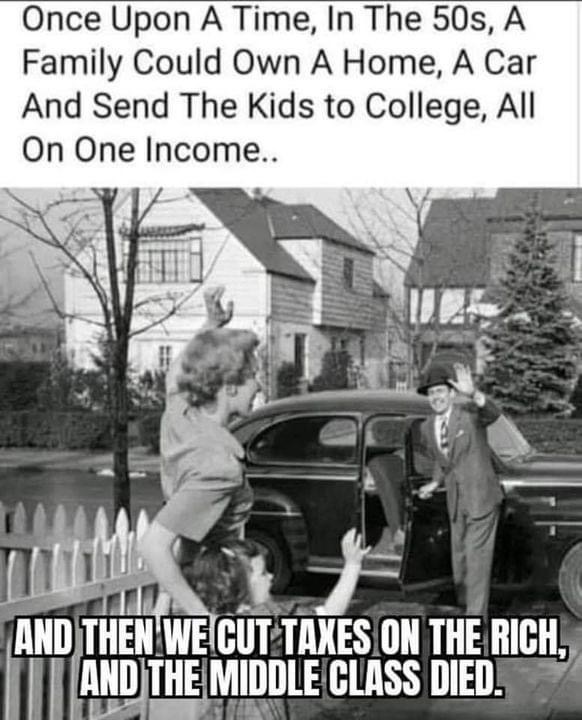

Of course, one model for early police forces in the United States was the London Metropolitan Police of Sir Robert Peel. Peel’s police force focused on the protection of property and putting down strikes. Another far more sinister model is found in the Slave Patrols of the southern confederacy and the Texas Rangers. The impetus for both of these forces was to protect the property and financial interests of wealthy benefactors.

When we look at the influence of Peel, his efforts tend to be presented as a “noble endeavor.” Yet as Vitale points out, the core of his mission was not of crime-fighting; it was focused on managing disorder and protecting the propertied classes from the unwashed masses. Peel developed his ideas while managing the British colonial occupation of Ireland, where he struggled to foster new forms of social control that would allow for its continued political and economic domination in the face of growing uprisings (Vitale, 2017).

The London model was then imported to the U.S. beginning in Boston in 1838 and continuing through the northern cities over the next few decades. Massive immigration and rapid industrialization created an even more socially and politically chaotic environment than in the U.K.: New York was exploding with new immigrants who were being chewed up by a rapid and imiserating industrialization. Rioting was widespread during this period, occurring on a monthly basis for many years. After the 1828 Christmas riot, when 4,000 workers marched on the wealthy districts, newspapers began calling for a major expansion and professionalization of the night watch, which eventually led to the formation of the police (Vitale, 2017).

The Slave Model

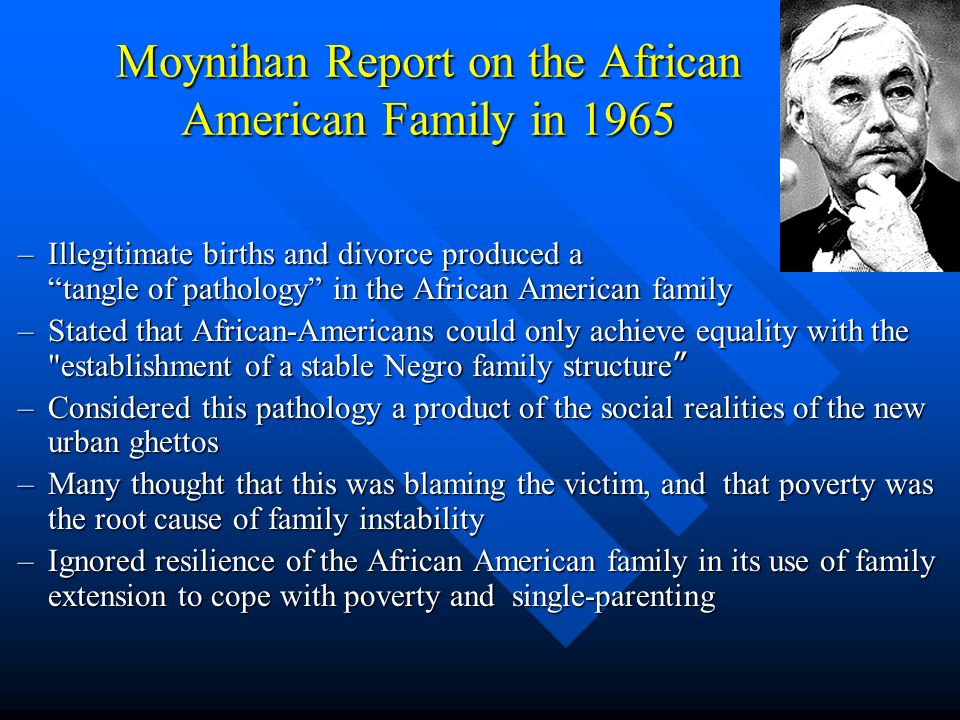

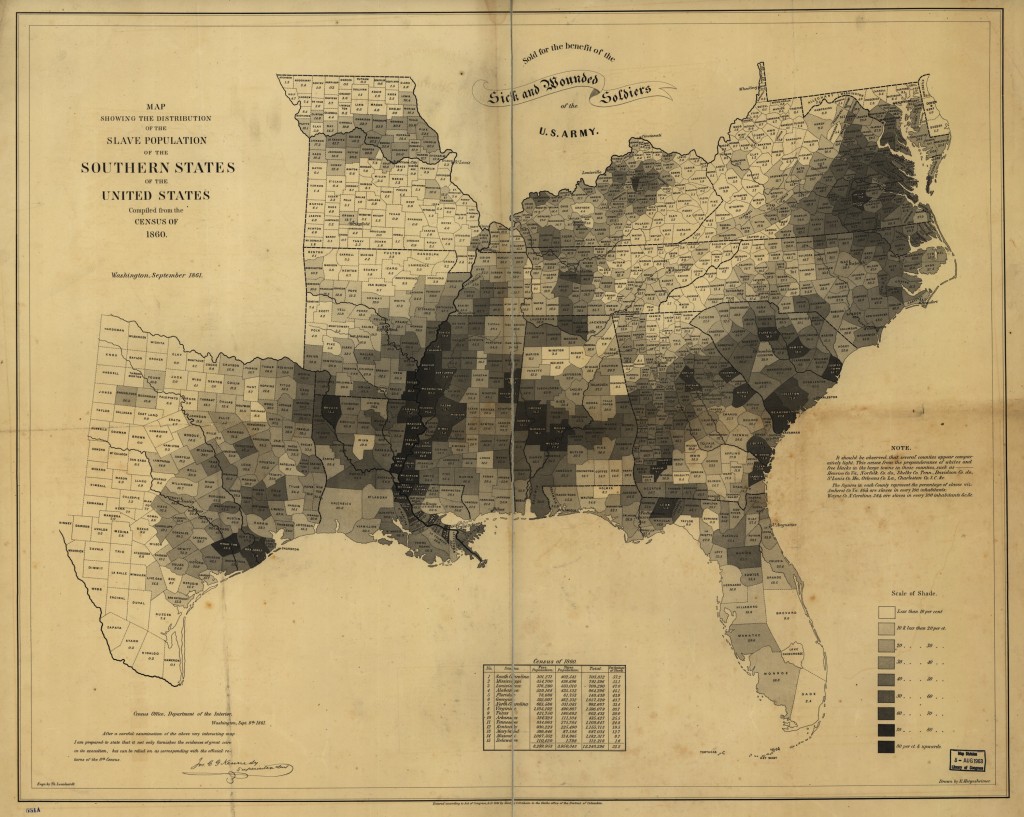

Whereas in the industrial North police helped elites to keep control over their unruly, often immigrant, working-class populations, things evolved differently in the South. In the South, police were organized to help plantation owners break up efforts by slaves to organize. When they attempted to leave, even after being freed, they found ways to detain them for trivial offenses [in the case of the Texas Rangers, they were employed by wealthy settlers who were intent on stealing Mexican land].

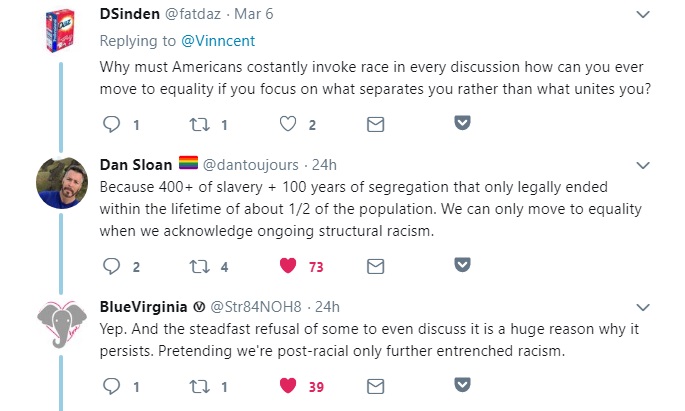

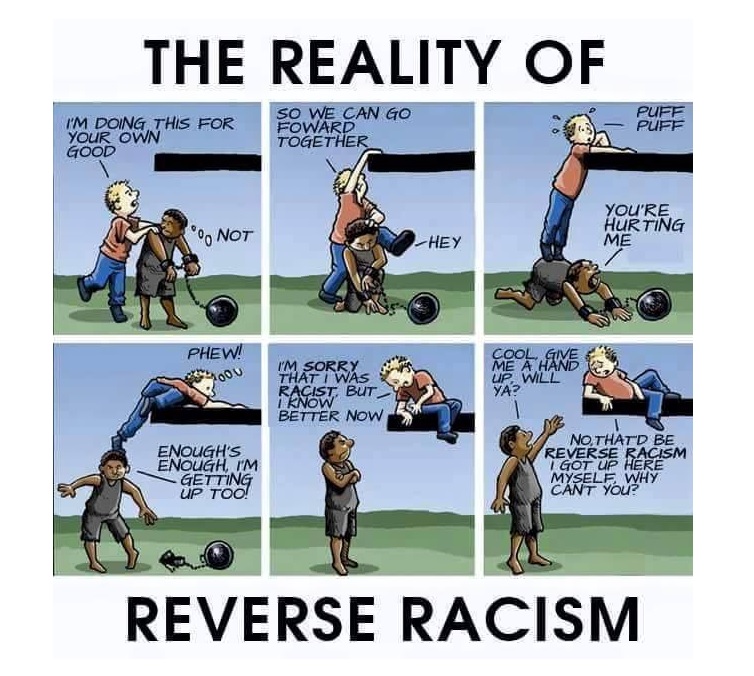

The importance of this history to modern policing cannot be overstated. Why is it important? On the one hand, it helps to bring into awareness an important narrative that helps frame police violence against black people; a social fact that is particularly relevant to our contemporary moment. On the other hand, it can foster discussion and understanding, as it creates a point of entry into a conversation: What is happening in modern policing? What has changed over time? What has remained the same? How is the historical social context relevant to the situation we find ourselves in today?

Given all of this, we can draw from this history to observe similarities as well as contradictions. The violence as it was manifest in the form of slave patrols is not of the same order as the violence evident in contemporary police actions, who may be involved in BOTH protecting moneyed interests as well as working to reduce crime in black communities.

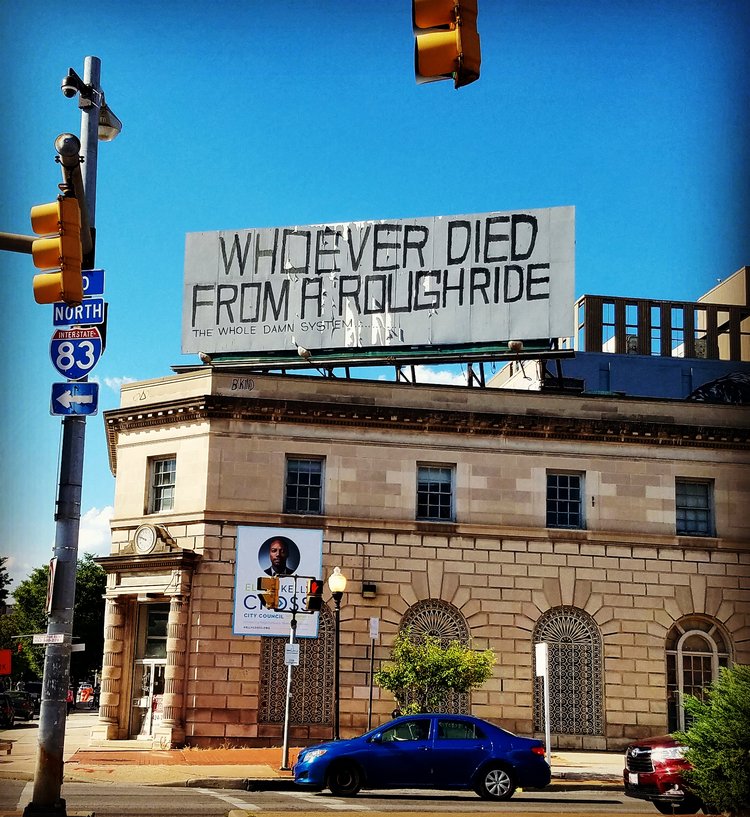

Police Brutality – Then vs. Now

In the old days, (early 20th century), police brutality was a concern for different reasons than it is today. At the turn of the century, most of the police force was made up of Irish Americans. That is to say, there was an important social class and ethnic identity component embedded in the criticism of the police. Metropolitan police reformers were chiefly concerned with addressing the problem of corruption in cities. Of foremost concern was how police tended to be deeply embedded in the machine politics of cities. This made them a prime target for reform.

Some might argue that very little has changed in this regard. Police corruption is still a factor; however, it presents itself in different ways now. Whereas in the late nineteenth century, it was about extracting extortion money from criminals. For instance, there were robust relationships between brothel madams and the police that created a community of interest between the two. Today, police corruption takes the form of either cooking the books on crime statistics or, as we saw in the case of the Illinois police officer very recently, embezzling department funds.

Why Does This History Matter Today?

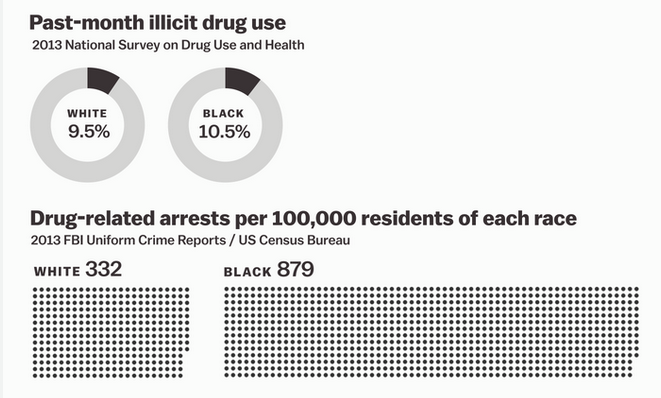

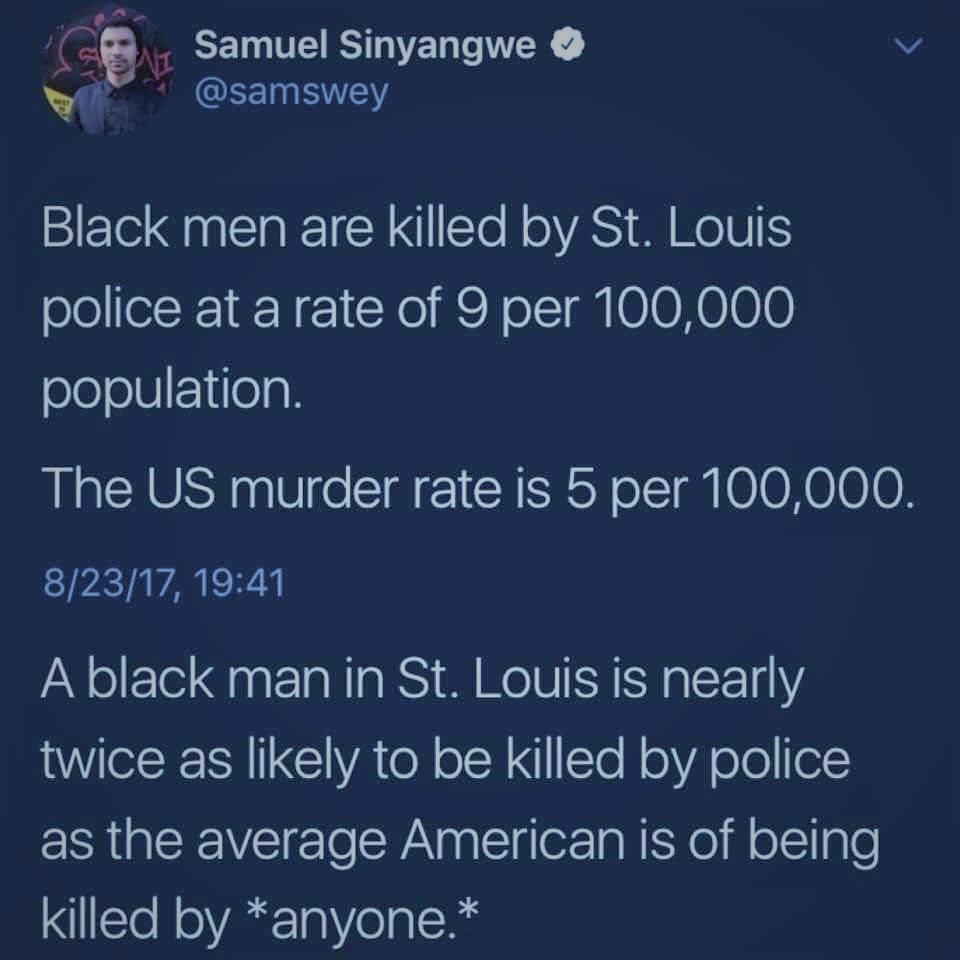

Understanding the past role played by police can tell us a lot about the patterns of violence we see in our modern police forces. Instead of seeing police brutality and the targeting of black people as a newly evolved “anomaly” we can see it for what it is: an echo of past practice. It is important to recognize the historical resonances that are present here if we ever hope to change some of the current problems in contemporary policing, especially as this relates to police violence in communities of color.

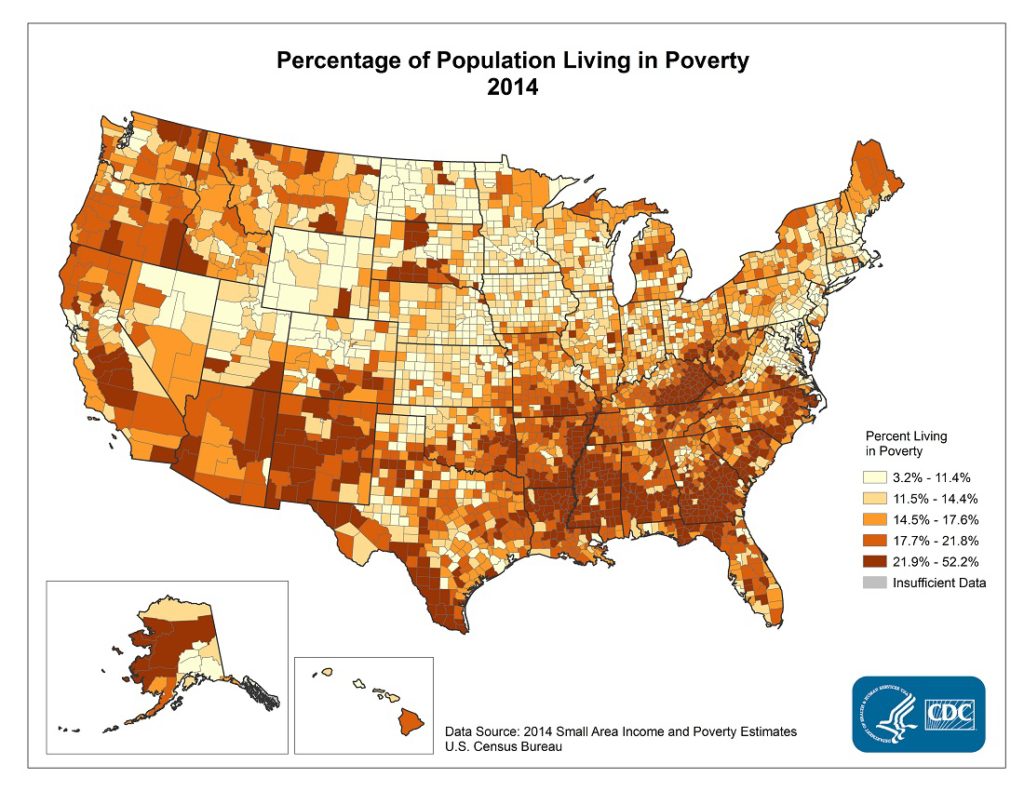

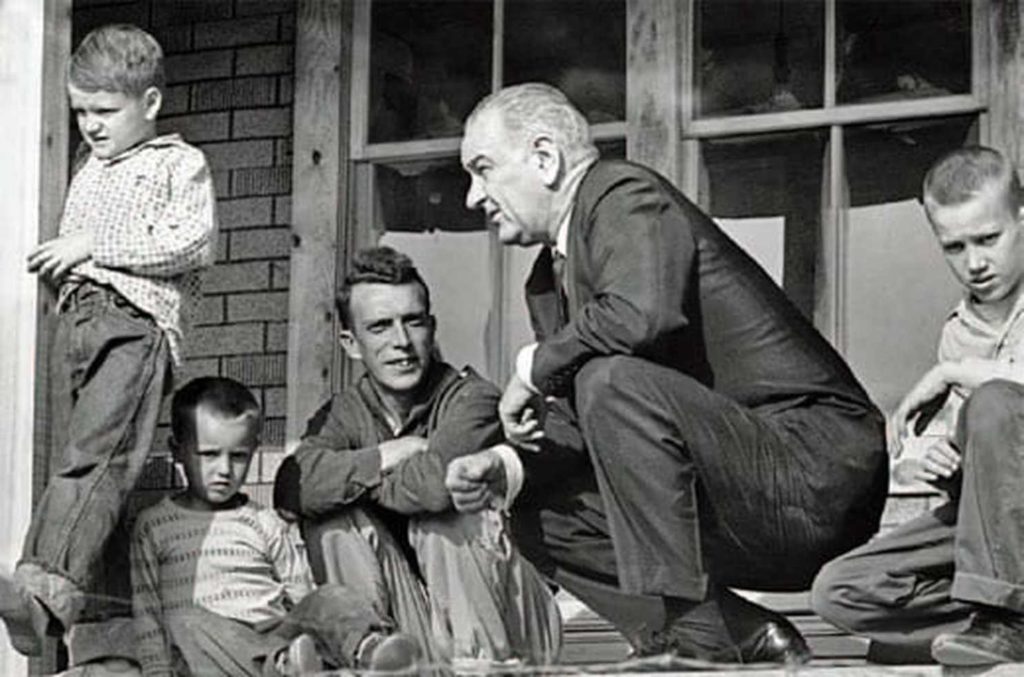

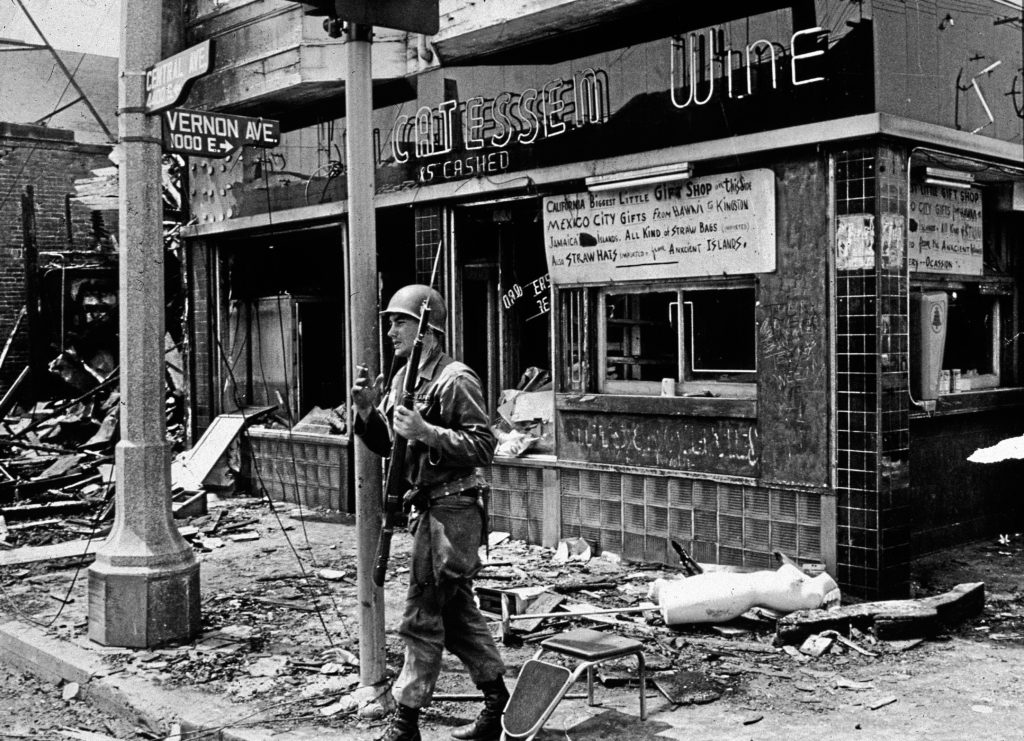

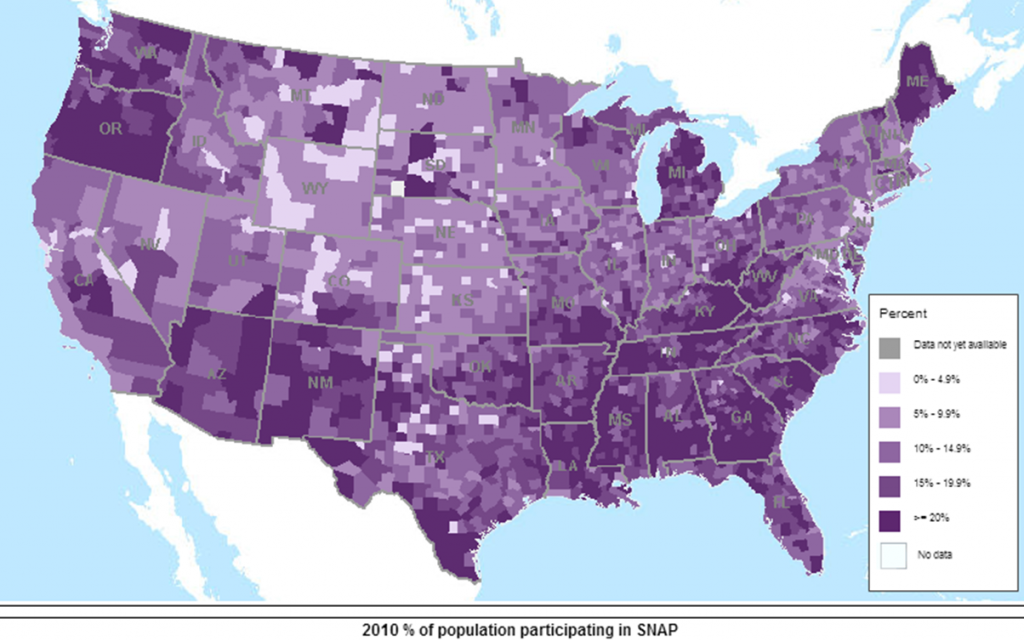

Lets take Ferguson Missouri as an example. The main reason police had so much contact with black people in Ferguson was related to financial developments there – namely, a loss of revenue due to imposed budget cuts. Given the weak tax base (a reflection of low property values), the police there compensated by generating alternative revenue in the form of fines. That is to say, they seized upon a community of poor people and attempted to extract something from them that they didn’t have – money. Over time, the relationship with residents deteriorated to the point of boiling over into street violence.

While this is arguably somewhat different than in the late 19th. century, it shares some resonance, as law enforcement in Western areas of the U.S. often operated on a fee-based patronage system. Under this system of control, the U.S. government invested U.S. marshals with the power to extract fees from the population in the form of court fees. This gave rise to a system where the marshals would often arrest people for questionable offenses, as the goal was to generate revenue from court fees. That is similar to what happened in Ferguson (police, even though they are paid a salary, are still paid indirectly from fees and fines that are collected by the courts).

The lesson learned in the 19th. century that apparently still needs to be learned again is that when you provide incentives to police to fight crime for money, they will do what you ask them to do.

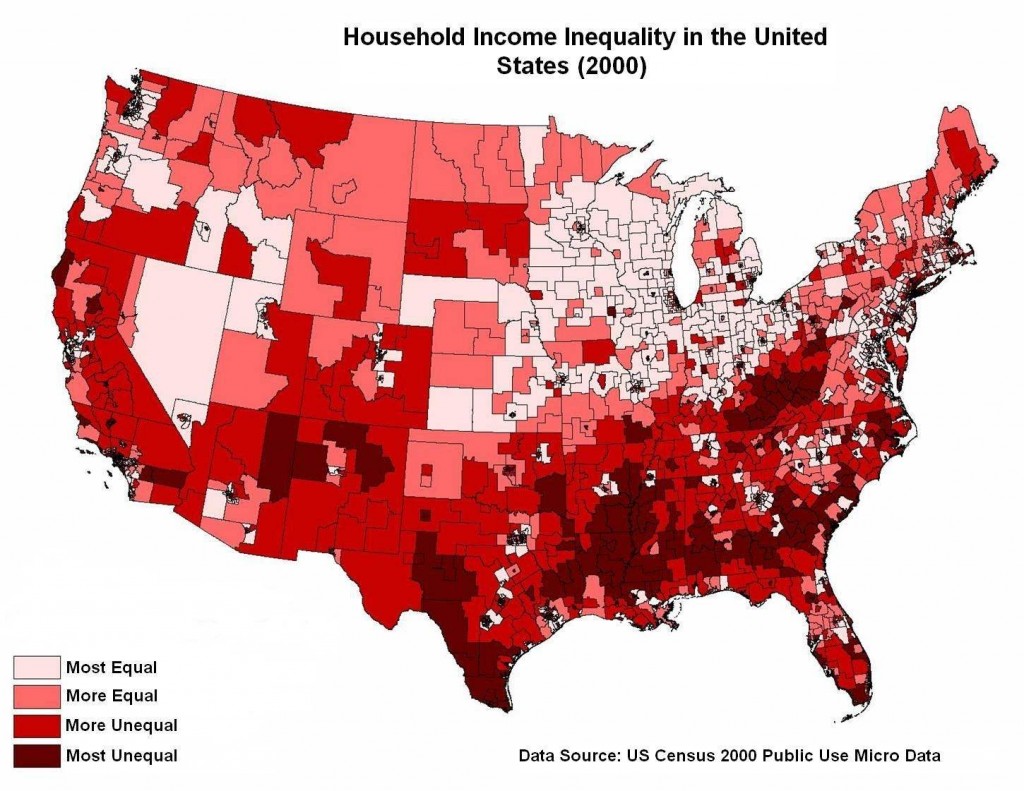

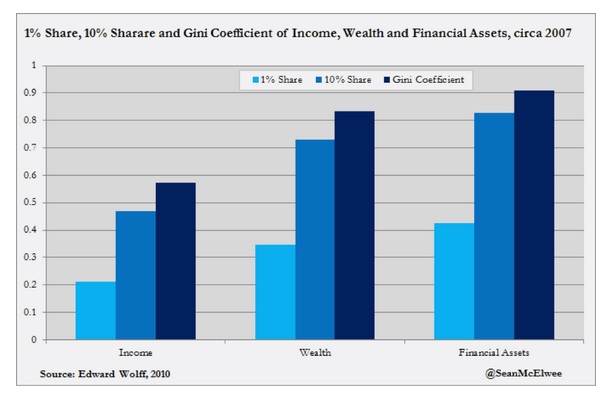

Police and Social Inequality

Consequently, even as the stated mission of the police has evolved to one that extols its ability to “Serve and Protect,” Vitale argues to contrary. He maintains that the police continue to operate, as evidenced by their actions and practice, that they remain consistent with their origins. According to Vitale:

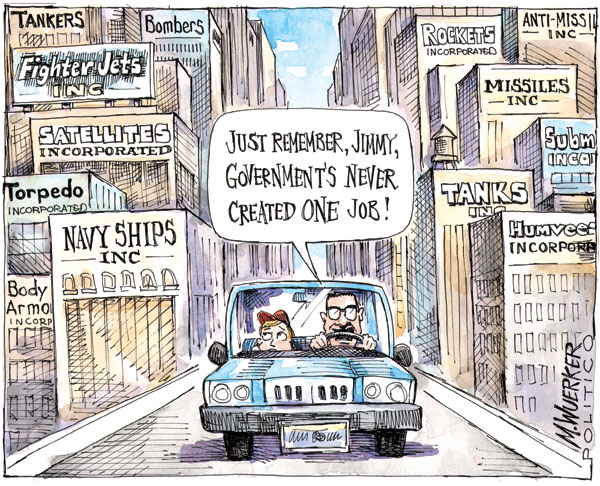

The reality is that the police have always been at the root of a system for managing and producing inequality. This is accomplished by suppressing social movements and tightly managing the behaviors of poor and nonwhite people in ways that benefit those already in positions of economic and political power. Police have always functioned as a force for controlling those on the losing end of these economic and political arrangements, quelling social upheavals that could no longer be managed by existing private, communal, and informal processes. This can be seen in the earliest origins of policing, which were tied to three basic social arrangements of inequality in the 18thcentury: slavery, colonialism, and the control of an industrial working class.

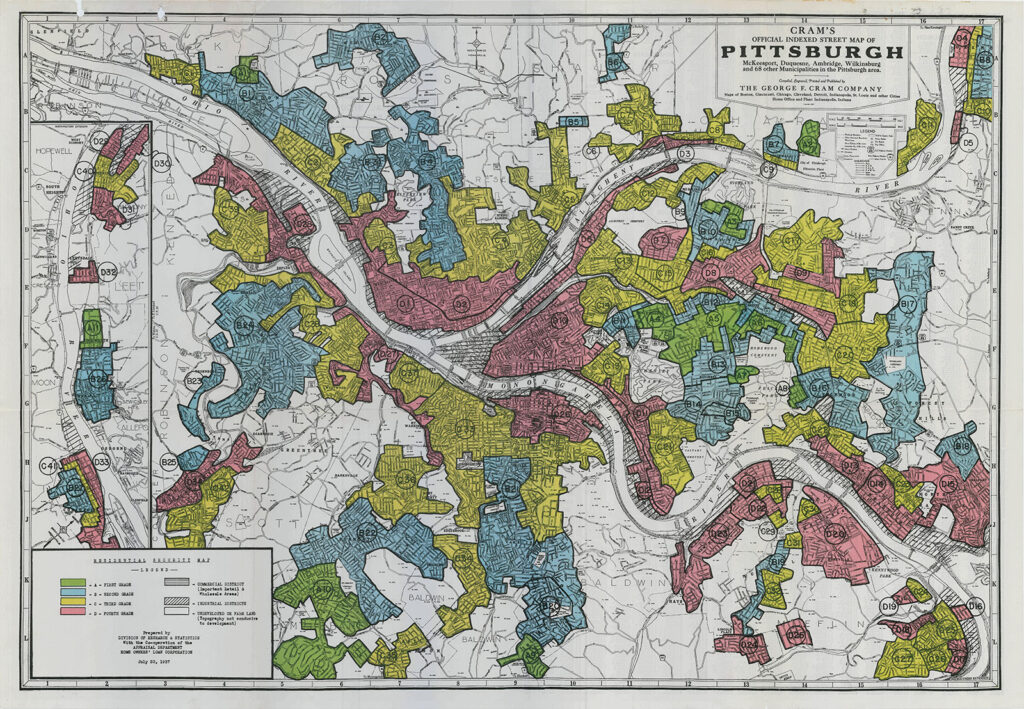

In short, policing was built upon the bulwark of slavery (and the very backs of slaves) as it unfolded in the Confederacy of the United States. The role of the slave patrols was not to simply operate as “hired hands” of plantations; police became embedded within the profit motive and raison d’etre of the plantations. Put another way, police protected white economic and cultural power; they shored up profitability by ensuring that a racialized group of people – black people – would be perpetually hunted, socially disenfranchised, and kept as property, if not always for the plantation, but the state itself.

According to Vitale, “this created what Allan Silver called a “policed society,” in which state power was significantly expanded to face down the demands for justice from those subject to these systems of domination and exploitation. Or, as Kristian Williams points out, “the police represent the point of contact between the coercive apparatus of the state and the lives of its citizens.”

Serve and Protect Who?

The emphasis on the public safety mission of police, says Vitale, has partly been driven by the desire of more liberal politicians to legitimize the force in the eyes of the population. And, as Vitale points out, everyone wants to live in safe communities. But in the past few decades, as inequality has increased, police forces have both been expanded and given increasingly lethal weapons. Training, rather than emphasizing de-escalation techniques and respectful treatment of people, has been focused on promoting police safety through quick, violent reaction to perceived threats Vitale, 2017).

How Are Private Policing Agencies Bound Up in This History?

Long before there was a Federal Bureau of Investigation, there was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. The agency was established in the United States by a Scotsman, Allan Pinkerton. Pinkerton was at one time the largest private law enforcement organization in the world. Historian Frank Morn writes: “By the mid-1850s a few businessmen saw the need for greater control over their employees; their solution was to sponsor a private detective system. In February 1855, Allan Pinkerton, after consulting with six Midwestern railroads, created such an agency in Chicago.”

Pinkerton’s agents performed a variety of services for the people who hired them; this included basic security guard work, strike-breaking, and private military contract work.

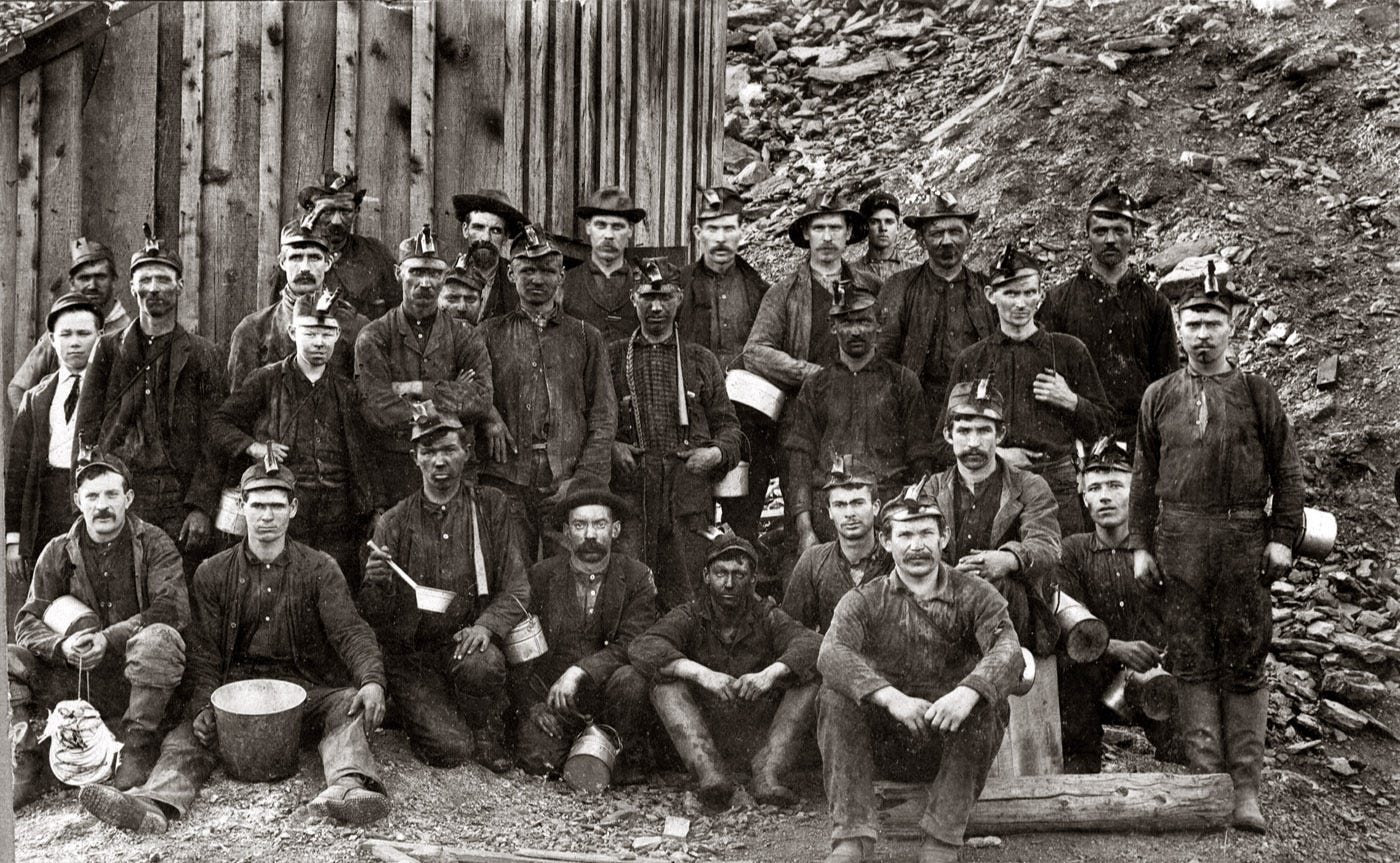

During the labor strikes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, businessmen hired the Pinkerton Agency to infiltrate unions. They provided guards to help keep strikers and union organizers out of factories; in some cases, they were employed to intimidate workers. The Pinkertons were also employed as guards in coal, iron, and lumber disputes in states that included Illinois, Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

As Vitale Points out, the early police forces were created specifically to suppress workers’ movements. Pennsylvania, as it turns out, was home to some of the most militant unionism, resulting in numerous strikes and violent confrontations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Local police were sometimes sympathetic toward the workers who were often the bulk of local constituents, so mine and factory owners turned to the state to provide them with armed forces to control strikes and intimidate organizers.

The Coal and Iron Police committed numerous atrocities, including the Latimer Massacre of 1897, in which they killed 19 unarmed miners and wounded 32 others. The final straw was the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902, in which miners and employers waged a pitched battle that lasted five months and created national coal shortages.

Pinkerton’s Landing Bridge, Homestead, Pa

The Battle of Homestead

One of the most famous and bloody strikes of the nineteenth century occurred in Homestead, Pennsylvania. In 1892, the wealthy industrialist Andrew Carnegie demanded production to be raised. This was a demand that the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers union refused.

The striking workers took control of the mill and sealed it off, effectively denying the company its own mill. Carnegie’s plant manager Henry Clay Frick then hired a police force of Pinkerton Detectives to take back the mill using armed force if necessary. Industrialists like Frick employed Pinkertons to spy on their unions. The police acted as strikebreakers and were often implicated as agents provocateurs, fomenting violence as a way of justifying their continued paychecks.

Three hundred Pinkerton Detectives armed with rifles boarded barges and sailed up the river in the early hours of July 6, 1892. After arriving at the plant on the river barges, the Pinkerton agents squared off with thousands of striking workers in an all-day battle waged with guns, bricks, and even dynamite. But as it turned out, the strikers had discovered the plan and roused the town at 2:00 a.m. to defend the plant from the Pinkerton invasion. When the private police force made landfall they were meet with thousands of strikers and their families, who worked together to drive them off.

Before this, the State of Pennsylvania’s initial response to the uprising had been to authorize a privatized police – the Coal and Iron Police. Local employers had only to pay a commission fee of $1 dollar each to deputize anyone of their choosing to be an officer of the law working directly for the employer, under the supervision of the Pinkertons or other private security forces.

In the end, the vastly outnumbered Pinkertons surrendered. More than a dozen people were left dead ( 3 Pinkertons and 6 steelworkers) and others were wounded. On November 20, the strike officially ended and Carnegie achieved control over his labor force again.

The fallout from the melee crippled the steel union, but it also branded the Pinkertons as “hired thugs,” leading several states to pass laws banning the use of outside guards in labor disputes. In the aftermath, political leaders and employers decided that a new, more legitimate-seeming system of labor management was needed, to be paid for out of the public coffers. The result was the creation of the Pennsylvania State Police in 1905.

While Frick’s hardline stance ultimately led to the demise of the union the Pinkertons role in the conflict helped cement their reputation as the paramilitary wing of big business. Anarchists would later unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Frick. The broken union in Homestead eventually joined the United Steel Workers, formed later in 1942. The Homestead Strike still stands out in history as an example of how difficult it remains for unions to contest the power of management and secure the interests of workers.

“Pinkerton’s Landing Bridge,” as it is now known, is the nickname given to the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad Bridge at Munhall. The bridge crosses the Monongahela River between Muhall, Pa and Rankin, Pa.

Other Pinkerton confrontations that are noteworthy include the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Battle of Blair Mountain (West Virginia) in 1921.

Pinkertons Inspired the Term “Private Eye”

The Pinkerton agency first made its name in the late-1850s for hunting down outlaws and providing private security for railroads. As the company’s profile grew, its iconic logo—a large, unblinking eye accompanied by the slogan “We Never Sleep”—gave rise to the term “private eye” as a nickname for detectives.

Pinkertons Hired the Nation’s First Female Detective

In 1856, 23-year-old widow Kate Warne walked into Pinkerton’s Chicago office and requested a job as a detective. Allan Pinkerton was hesitant to hire a female investigator, but he gave in after Warne convinced him that she could “worm out secrets in many places to which it was impossible for male detectives to gain access.” True to her word, Warne proved to be an expert at working undercover, once busting a thief by cozying up to his wife and convincing her to reveal the location of the loot. During another case, she got a suspect to feed her crucial information by disguising herself as a fortune-teller. Pinkerton would later list Warne as one of the best investigators he ever hired. Following her death in 1868, he even had her buried in his family plot.

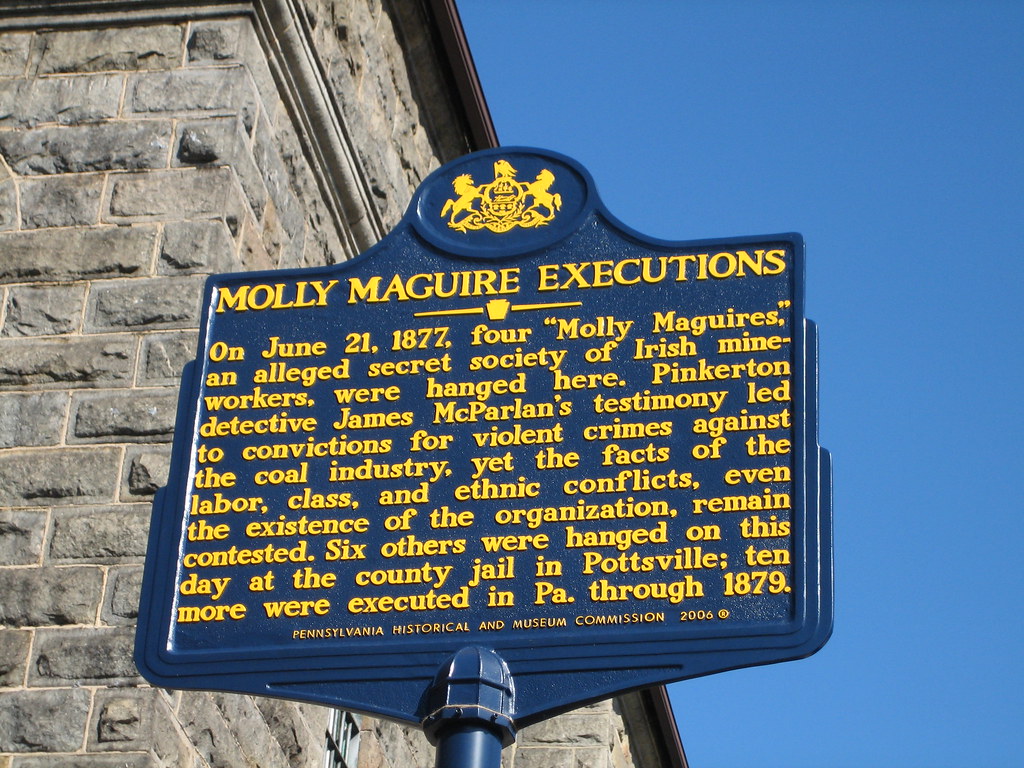

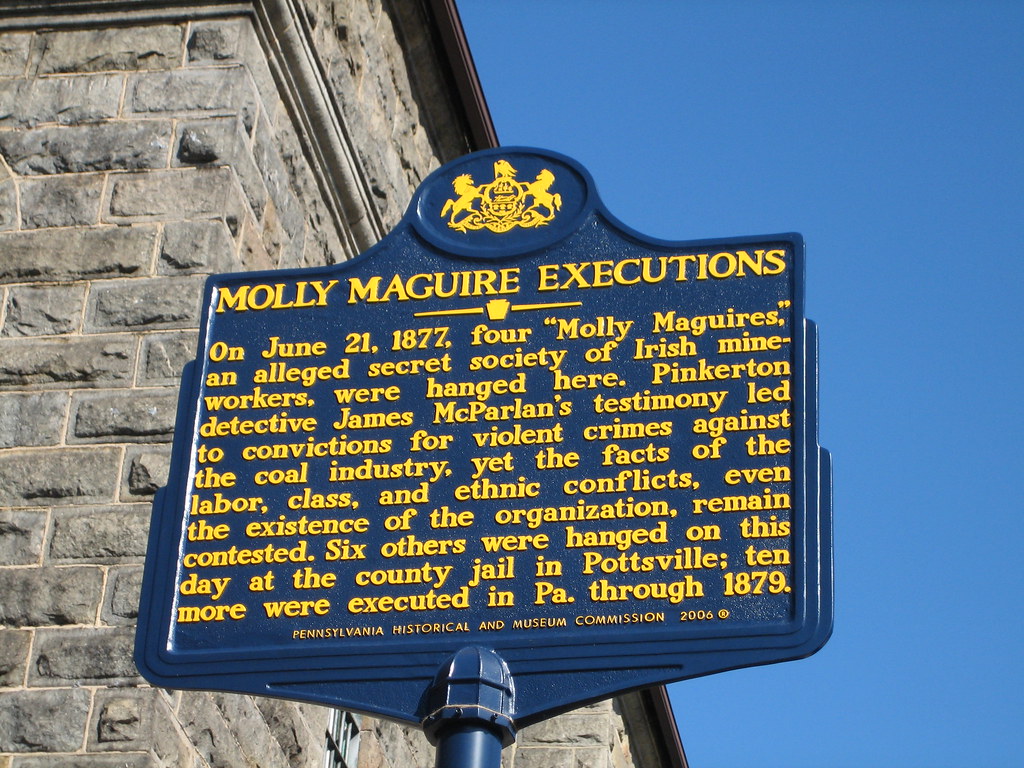

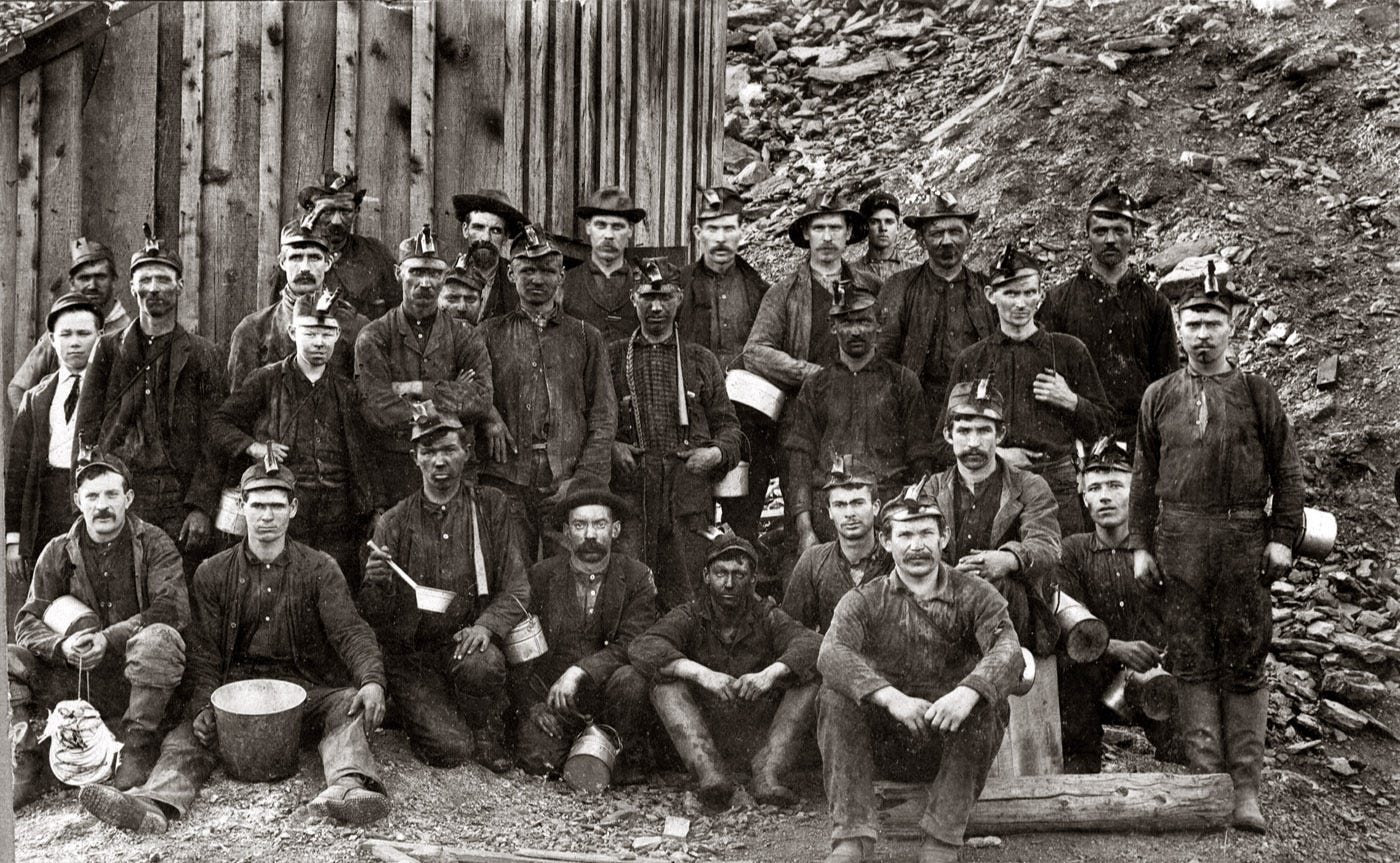

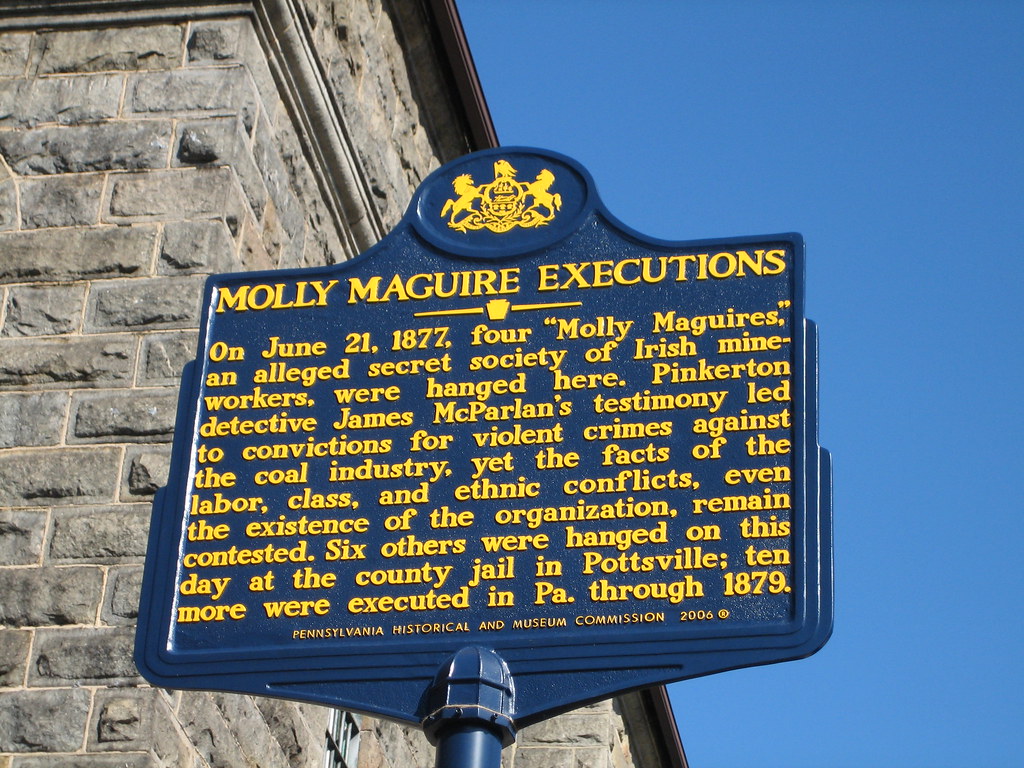

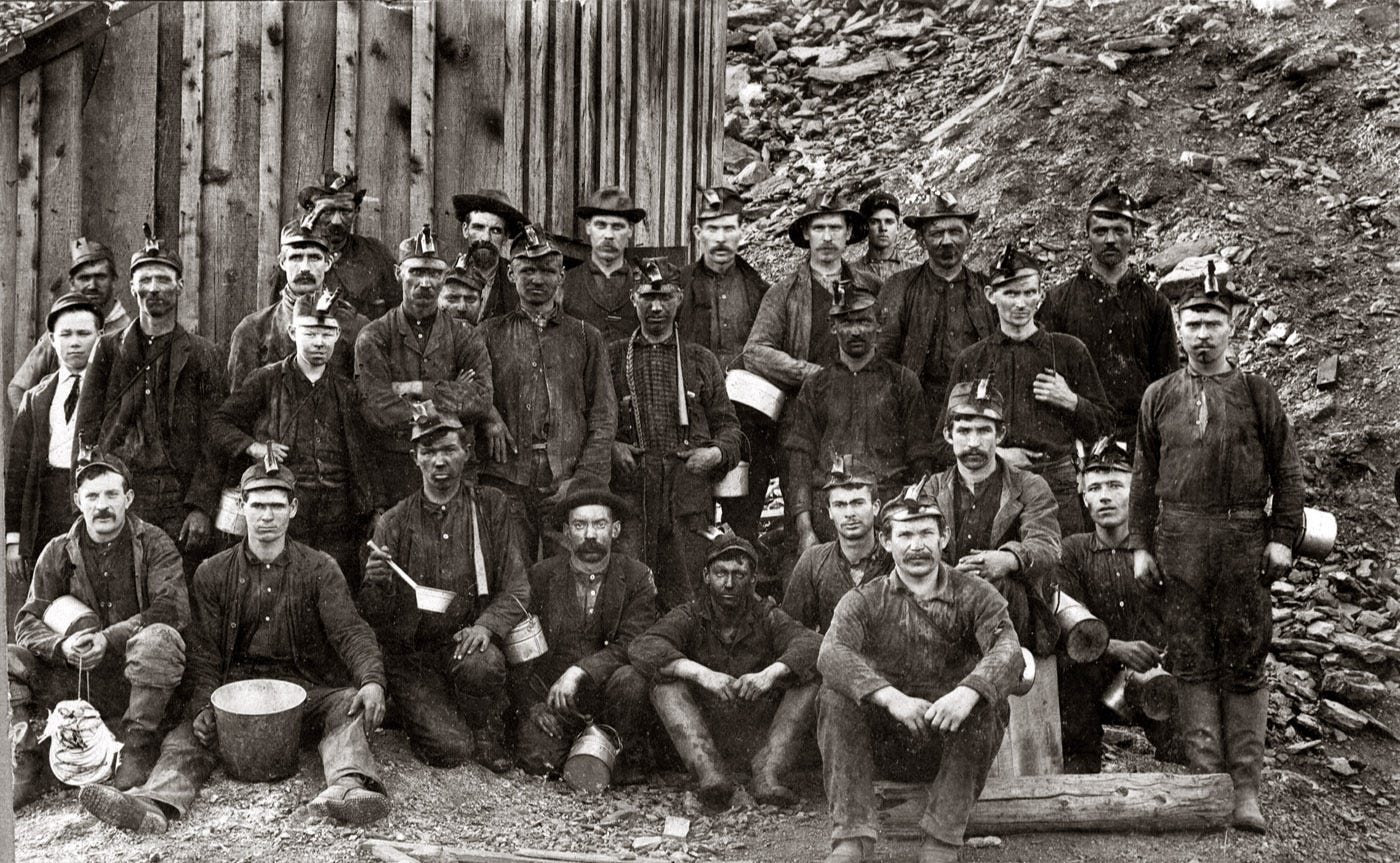

Molly Maguires

In the 1870s, Franklin B. Gowen, President of the Philadelphia Reading Railroad, hired the agency to “investigate” its labor unions in the company’s mines. When mine owners and managers docked pay and benefits, some Mollies, as they were known to locals, killed whoever stood in the Irish miner’s way of a better life. A Pinkerton agent, James McParland, using the alias “James McKenna”, infiltrated the Molly Maguires, a 19th-century secret-society of mainly Irish-American coal miners, which ultimately lead to the downfall of the labor organization.

Molly Maguires

Pinkertons May Have Foiled a Presidential Assassination Attempt

Shortly before Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration in March 1861, Allan Pinkerton traveled to Baltimore on a mission for a railroad company. He was investigating rumors that Southern sympathizers might sabotage the rail lines to Washington, D.C., but while gathering undercover intelligence, he learned that a secret cabal also planned to assassinate Lincoln, who was at that time on a whistle-stop tour, as he switched trains in Baltimore on his way to the capital.

Pinkerton tracked down the president-elect and informed him of the alleged plot. With the help of Kate Warne and several other agents, he then arranged for Lincoln to secretly board an overnight train and pass through Baltimore several hours ahead of his published schedule. Pinkerton operatives also cut telegraph lines to ensure the conspirators couldn’t communicate with one another, and Warne had Lincoln pose as her invalid brother to cover up his identity. The president-elect arrived safely in Washington the next morning, but his decision to skirt through Baltimore saw him lampooned and labeled a coward in the press. Meanwhile, none of the would-be assassins was ever arrested, leading some historians to conclude that the threat may have been exaggerated or even invented by Pinkerton.

Pinkertons Spied for the Union Army During the Civil War

Allan Pinkerton was a staunch abolitionist and Union man, and during the Civil War, he organized a secret intelligence service for General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Operating under the name E.J. Allen, Pinkerton set up spy rings behind enemy lines and infiltrated southern sympathizer groups in the North. He even had agents interview escaped slaves to glean information about the Confederacy.

Pinkertons Created One of the First Criminal Databases

One of the many ways the Pinkertons revolutionized law enforcement was with their so-called “Rogues’ Gallery,” a collection of mug shots and case histories that the agency used to research and keep track of wanted men. Along with noting suspects’ distinguishing marks and scars, agents also collected newspaper clippings and generated rap sheets detailing their previous arrests, known associates and areas of expertise. A more sophisticated criminal library wouldn’t be assembled until the early 20th century and the birth of the FBI.

Pinkerton Detectives guarding the coffin of actress Marilyn Monroe, 1962

Modern Era

Due to its history of conflicts with labor unions, the name Pinkerton continues to evoke negative associations. Pinkertons evolved over the course of time and diversified from labor spying following revelations publicized by the La Follette Committee hearings in 1937. The firm’s criminal detection work likewise suffered from the police modernization movement. Calls for increased police professionalization saw the rise of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the bolstering of detective services offered by local police forces. All of these developments caused the Pinkertons influence to diminish over time.

In 1999, the company was bought by Securitas AB, a Swedish security company. This was followed by the acquisition of a longtime Pinkerton rival, the William J. Burns Detective Agency, to create an additional division, Securitas Security Services USA. The company thus continues to live on as a private security firm and guard service, however, it operates under the shortened name “Pinkerton.”

So What Do We Do Now? How Do We Fix the Police?

Vitale argues we need to rethink the role of policing and to reduce the ways in which police are used in our society. Does that mean we should eliminate police forces altogether? Probably not. History doesn’t have to be the template from which we base our present operations. We can and must find a way to chart a path so that we can realize a more progressive form of policing that serves our modern society; one that is not based on reinforcing and exacerbating existing social inequalities.

As Vitale argues, we need people who are trained to deal with our most vulnerable and difficult populations; people who understand their point of view and who take seriously their role to help them, not just arrest, restrain and control them.

Beyond that, we need to deal with the manifest social problems that derive from maintaining a society in which large parts of the population are considered surplus or undeserving.

Sources

“The Myth of Liberal Policing,” by Alex Vitale, 2017.

The End of Policing, by Alex Vitale, 2017.

“10 Things You May Not Know About the Pinkertons,” by Evan Andrews, 2015

Consequently, while the stated mission of the police might have changed to “Serve and Protect,” Vitale argues that they continue to operate, as demonstrated by police practice, in ways that are consistent with their origins. Vitale argues:

The reality is that the police have always been at the root of a system for managing and producing inequality. This is accomplished by suppressing social movements and tightly managing the behaviors of poor and nonwhite people in ways that benefit those already in positions of economic and political power. Police have always functioned as a force for controlling those on the losing end of these economic and political arrangements, quelling social upheavals that could no longer be managed by existing private, communal, and informal processes.

This can be seen in the earliest origins of policing, which were tied to three basic social arrangements of inequality in the 18thcentury: slavery, colonialism, and the control of an industrial working class.

In other words, policing was built upon the bulwark of slavery (and the backs of slaves) as this unfolded in the old Confederacy of the United States. The role of the slave patrols was not to simply operate as “hired hands” of plantations; they were embedded deep into the profit motive and raison d’etre of the plantations. Put another way, they protected white economic and cultural power; they shored up profitability by ensuring that a racialized group of black people would be perpetually hunted, socially disenfranchised, and kept as property, if not for the plantation, but rather for the state.

According to Vitale, “this created what Allan Silver called a “policed society,” in which state power was significantly expanded to face down the demands for justice from those subject to these systems of domination and exploitation. As Kristian Williams points out, “the police represent the point of contact between the coercive apparatus of the state and the lives of its citizens.”

The emphasis on the public safety mission of police, says Vitale, has partly been driven by the desire of more liberal politicians to legitimize the force in the eyes of the population. And, as Vitale points out, everyone wants to live in safe communities. But in the past few decades, as inequality has increased, police forces have both been expanded and given increasingly lethal weapons. Training, rather than emphasizing de-escalation techniques and respectful treatment of people, has been focused on promoting police safety through quick, violent reaction to perceived threats Vitale, 2017).

[Definition of “Liberal State”: Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy that espouses the values of liberty and equality. Liberal democracies espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but they generally support civil rights, democratic ideals, secular government, gender and racial equality, freedom of speech, press, and religion. Liberalism became a distinct movement during the Age of the Enlightenment when it became popular with Western philosophers and economists. Refuting norms of power based on heredity, monarchy, and the divine right of kings, liberalism sought to replace them with traditional conservatism, representative democracy, and rule of law. French liberalism emphasized rejecting authoritarianism linked to nation-building].

How Are Private Policing Agencies Bound Up in This History?

Long before there was a Federal Bureau of Investigation, there was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. The agency was established in the United States by a Scotsman, Allan Pinkerton. Pinkerton was at one time the largest private law enforcement organization in the world. Historian Frank Morn writes: “By the mid-1850s a few businessmen saw the need for greater control over their employees; their solution was to sponsor a private detective system. In February 1855, Allan Pinkerton, after consulting with six Midwestern railroads, created such an agency in Chicago.”

Pinkerton’s agents performed a variety of services for the people who hired them; this included basic security guard work, strike-breaking, and private military contract work.

During the labor strikes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, businessmen hired the Pinkerton Agency to infiltrate unions. They provided guards to help keep strikers and union organizers out of factories; in some cases, they were employed to intimidate workers. The Pinkertons were also employed as guards in coal, iron, and lumber disputes in states that included Illinois, Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

As Vitale Points out, the early police forces were created specifically to suppress workers’ movements. Pennsylvania, as it turns out, was home to some of the most militant unionism, resulting in numerous strikes and violent confrontations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Local police were sometimes sympathetic toward the workers who were often the bulk of local constituents, so mine and factory owners turned to the state to provide them with armed forces to control strikes and intimidate organizers.

The Coal and Iron Police committed numerous atrocities, including the Latimer Massacre of 1897, in which they killed 19 unarmed miners and wounded 32 others. The final straw was the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902, in which miners and employers waged a pitched battle that lasted five months and created national coal shortages.

Pinkerton’s Landing Bridge, Homestead, Pa

The Battle of Homestead

One of the most famous and bloody strikes of the nineteenth century occurred in Homestead, Pennsylvania. In 1892, the wealthy industrialist Andrew Carnegie demanded production to be raised. This was a demand that the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers union refused.

The striking workers took control of the mill and sealed it off, effectively denying the company its own mill. Carnegie’s plant manager Henry Clay Frick then hired a police force of Pinkerton Detectives to take back the mill using armed force if necessary. Industrialists like Frick employed Pinkertons to spy on their unions. The police acted as strikebreakers and were often implicated as agents provocateurs, fomenting violence as a way of justifying their continued paychecks.

Three hundred Pinkerton Detectives armed with rifles boarded barges and sailed up the river in the early hours of July 6, 1892. After arriving at the plant on the river barges, the Pinkerton agents squared off with thousands of striking workers in an all-day battle waged with guns, bricks, and even dynamite. But as it turned out, the strikers had discovered the plan and roused the town at 2:00 a.m. to defend the plant from the Pinkerton invasion. When the private police force made landfall they were meet with thousands of strikers and their families, who worked together to drive them off.

Before this, the State of Pennsylvania’s initial response to the uprising had been to authorize a privatized police – the Coal and Iron Police. Local employers had only to pay a commission fee of $1 dollar each to deputize anyone of their choosing to be an officer of the law working directly for the employer, under the supervision of the Pinkertons or other private security forces.

In the end, the vastly outnumbered Pinkertons surrendered. More than a dozen people were left dead ( 3 Pinkertons and 6 steelworkers) and others were wounded. On November 20, the strike officially ended and Carnegie achieved control over his labor force again.

The fallout from the melee crippled the steel union, but it also branded the Pinkertons as “hired thugs,” leading several states to pass laws banning the use of outside guards in labor disputes. In the aftermath, political leaders and employers decided that a new, more legitimate-seeming system of labor management was needed, to be paid for out of the public coffers. The result was the creation of the Pennsylvania State Police in 1905.

While Frick’s hardline stance ultimately led to the demise of the union the Pinkertons role in the conflict helped cement their reputation as the paramilitary wing of big business. Anarchists would later unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Frick. The broken union in Homestead eventually joined the United Steel Workers, formed later in 1942. The Homestead Strike still stands out in history as an example of how difficult it remains for unions to contest the power of management and secure the interests of workers.

“Pinkerton’s Landing Bridge,” as it is now known, is the nickname given to the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad Bridge at Munhall. The bridge crosses the Monongahela River between Muhall, Pa and Rankin, Pa.

Other Pinkerton confrontations that are noteworthy include the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Battle of Blair Mountain (West Virginia) in 1921.

Pinkertons Inspired the Term “Private Eye”

The Pinkerton agency first made its name in the late-1850s for hunting down outlaws and providing private security for railroads. As the company’s profile grew, its iconic logo—a large, unblinking eye accompanied by the slogan “We Never Sleep”—gave rise to the term “private eye” as a nickname for detectives.

Pinkertons Hired the Nation’s First Female Detective

In 1856, 23-year-old widow Kate Warne walked into Pinkerton’s Chicago office and requested a job as a detective. Allan Pinkerton was hesitant to hire a female investigator, but he gave in after Warne convinced him that she could “worm out secrets in many places to which it was impossible for male detectives to gain access.” True to her word, Warne proved to be an expert at working undercover, once busting a thief by cozying up to his wife and convincing her to reveal the location of the loot. During another case, she got a suspect to feed her crucial information by disguising herself as a fortune-teller. Pinkerton would later list Warne as one of the best investigators he ever hired. Following her death in 1868, he even had her buried in his family plot.

Molly Maguires

In the 1870s, Franklin B. Gowen, President of the Philadelphia Reading Railroad, hired the agency to “investigate” its labor unions in the company’s mines. When mine owners and managers docked pay and benefits, some Mollies, as they were known to locals, killed whoever stood in the Irish miner’s way of a better life. A Pinkerton agent, James McParland, using the alias “James McKenna”, infiltrated the Molly Maguires, a 19th-century secret-society of mainly Irish-American coal miners, which ultimately lead to the downfall of the labor organization.

Molly Maguires

Pinkertons May Have Foiled a Presidential Assassination Attempt

Shortly before Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration in March 1861, Allan Pinkerton traveled to Baltimore on a mission for a railroad company. He was investigating rumors that Southern sympathizers might sabotage the rail lines to Washington, D.C., but while gathering undercover intelligence, he learned that a secret cabal also planned to assassinate Lincoln, who was at that time on a whistle-stop tour, as he switched trains in Baltimore on his way to the capital.

Pinkerton tracked down the president-elect and informed him of the alleged plot. With the help of Kate Warne and several other agents, he then arranged for Lincoln to secretly board an overnight train and pass through Baltimore several hours ahead of his published schedule. Pinkerton operatives also cut telegraph lines to ensure the conspirators couldn’t communicate with one another, and Warne had Lincoln pose as her invalid brother to cover up his identity. The president-elect arrived safely in Washington the next morning, but his decision to skirt through Baltimore saw him lampooned and labeled a coward in the press. Meanwhile, none of the would-be assassins was ever arrested, leading some historians to conclude that the threat may have been exaggerated or even invented by Pinkerton.

Pinkertons Spied for the Union Army During the Civil War

Allan Pinkerton was a staunch abolitionist and Union man, and during the Civil War, he organized a secret intelligence service for General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Operating under the name E.J. Allen, Pinkerton set up spy rings behind enemy lines and infiltrated southern sympathizer groups in the North. He even had agents interview escaped slaves to glean information about the Confederacy.

Pinkertons Created One of the First Criminal Databases

One of the many ways the Pinkertons revolutionized law enforcement was with their so-called “Rogues’ Gallery,” a collection of mug shots and case histories that the agency used to research and keep track of wanted men. Along with noting suspects’ distinguishing marks and scars, agents also collected newspaper clippings and generated rap sheets detailing their previous arrests, known associates and areas of expertise. A more sophisticated criminal library wouldn’t be assembled until the early 20th century and the birth of the FBI.

Pinkerton Detectives guarding the coffin of actress Marilyn Monroe, 1962

Modern Era

Due to its history of conflicts with labor unions, the name Pinkerton continues to evoke negative associations. Pinkertons evolved over the course of time and diversified from labor spying following revelations publicized by the La Follette Committee hearings in 1937. The firm’s criminal detection work likewise suffered from the police modernization movement. Calls for increased police professionalization saw the rise of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the bolstering of detective services offered by local police forces. All of these developments caused the Pinkertons influence to diminish over time.

In 1999, the company was bought by Securitas AB, a Swedish security company. This was followed by the acquisition of a longtime Pinkerton rival, the William J. Burns Detective Agency, to create an additional division, Securitas Security Services USA. The company thus continues to live on as a private security firm and guard service, however, it operates under the shortened name “Pinkerton.”

So What Do We Do Now? How Do We Fix the Police?

Vitale argues we need to rethink the role of policing and to reduce the ways in which police are used in our society. Does that mean we should eliminate police forces altogether? Probably not. History doesn’t have to be the template from which we base our present operations. We can and must find a way to chart a path so that we can realize a more progressive form of policing that serves our modern society; one that is not based on reinforcing and exacerbating existing social inequalities.

As Vitale argues, we need people who are trained to deal with our most vulnerable and difficult populations; people who understand their point of view and who take seriously their role to help them, not just arrest, restrain and control them.

Beyond that, we need to deal with the manifest social problems that derive from maintaining a society in which large parts of the population are considered surplus or undeserving.

Sources

“The Myth of Liberal Policing,” by Alex Vitale, 2017.

The End of Policing, by Alex Vitale, 2017.

“10 Things You May Not Know About the Pinkertons,” by Evan Andrews, 2015

Consequently, while the stated mission of the police might have changed to “Serve and Protect,” Vitale argues that they continue to operate, as demonstrated by police practice, in ways that are consistent with their origins. Vitale argues:

The reality is that the police have always been at the root of a system for managing and producing inequality. This is accomplished by suppressing social movements and tightly managing the behaviors of poor and nonwhite people in ways that benefit those already in positions of economic and political power. Police have always functioned as a force for controlling those on the losing end of these economic and political arrangements, quelling social upheavals that could no longer be managed by existing private, communal, and informal processes.

This can be seen in the earliest origins of policing, which were tied to three basic social arrangements of inequality in the 18thcentury: slavery, colonialism, and the control of an industrial working class.

In other words, policing was built upon the bulwark of slavery (and the backs of slaves) as this unfolded in the old Confederacy of the United States. The role of the slave patrols was not to simply operate as “hired hands” of plantations; they were embedded deep into the profit motive and raison d’etre of the plantations. Put another way, they protected white economic and cultural power; they shored up profitability by ensuring that a racialized group of black people would be perpetually hunted, socially disenfranchised, and kept as property, if not for the plantation, but rather for the state.

According to Vitale, “this created what Allan Silver called a “policed society,” in which state power was significantly expanded to face down the demands for justice from those subject to these systems of domination and exploitation. As Kristian Williams points out, “the police represent the point of contact between the coercive apparatus of the state and the lives of its citizens.”

The emphasis on the public safety mission of police, says Vitale, has partly been driven by the desire of more liberal politicians to legitimize the force in the eyes of the population. And, as Vitale points out, everyone wants to live in safe communities. But in the past few decades, as inequality has increased, police forces have both been expanded and given increasingly lethal weapons. Training, rather than emphasizing de-escalation techniques and respectful treatment of people, has been focused on promoting police safety through quick, violent reaction to perceived threats Vitale, 2017).

[Definition of “Liberal State”: Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy that espouses the values of liberty and equality. Liberal democracies espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but they generally support civil rights, democratic ideals, secular government, gender and racial equality, freedom of speech, press, and religion. Liberalism became a distinct movement during the Age of the Enlightenment when it became popular with Western philosophers and economists. Refuting norms of power based on heredity, monarchy, and the divine right of kings, liberalism sought to replace them with traditional conservatism, representative democracy, and rule of law. French liberalism emphasized rejecting authoritarianism linked to nation-building].

How Are Private Policing Agencies Bound Up in This History?

Long before there was a Federal Bureau of Investigation, there was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. The agency was established in the United States by a Scotsman, Allan Pinkerton. Pinkerton was at one time the largest private law enforcement organization in the world. Historian Frank Morn writes: “By the mid-1850s a few businessmen saw the need for greater control over their employees; their solution was to sponsor a private detective system. In February 1855, Allan Pinkerton, after consulting with six Midwestern railroads, created such an agency in Chicago.”

Pinkerton’s agents performed a variety of services for the people who hired them; this included basic security guard work, strike-breaking, and private military contract work.

During the labor strikes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, businessmen hired the Pinkerton Agency to infiltrate unions. They provided guards to help keep strikers and union organizers out of factories; in some cases, they were employed to intimidate workers. The Pinkertons were also employed as guards in coal, iron, and lumber disputes in states that included Illinois, Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

As Vitale Points out, the early police forces were created specifically to suppress workers’ movements. Pennsylvania, as it turns out, was home to some of the most militant unionism, resulting in numerous strikes and violent confrontations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Local police were sometimes sympathetic toward the workers who were often the bulk of local constituents, so mine and factory owners turned to the state to provide them with armed forces to control strikes and intimidate organizers.

The Coal and Iron Police committed numerous atrocities, including the Latimer Massacre of 1897, in which they killed 19 unarmed miners and wounded 32 others. The final straw was the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902, in which miners and employers waged a pitched battle that lasted five months and created national coal shortages.

Pinkerton’s Landing Bridge, Homestead, Pa

The Battle of Homestead

One of the most famous and bloody strikes of the nineteenth century occurred in Homestead, Pennsylvania. In 1892, the wealthy industrialist Andrew Carnegie demanded production to be raised. This was a demand that the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers union refused.

The striking workers took control of the mill and sealed it off, effectively denying the company its own mill. Carnegie’s plant manager Henry Clay Frick then hired a police force of Pinkerton Detectives to take back the mill using armed force if necessary. Industrialists like Frick employed Pinkertons to spy on their unions. The police acted as strikebreakers and were often implicated as agents provocateurs, fomenting violence as a way of justifying their continued paychecks.

Three hundred Pinkerton Detectives armed with rifles boarded barges and sailed up the river in the early hours of July 6, 1892. After arriving at the plant on the river barges, the Pinkerton agents squared off with thousands of striking workers in an all-day battle waged with guns, bricks, and even dynamite. But as it turned out, the strikers had discovered the plan and roused the town at 2:00 a.m. to defend the plant from the Pinkerton invasion. When the private police force made landfall they were meet with thousands of strikers and their families, who worked together to drive them off.

Before this, the State of Pennsylvania’s initial response to the uprising had been to authorize a privatized police – the Coal and Iron Police. Local employers had only to pay a commission fee of $1 dollar each to deputize anyone of their choosing to be an officer of the law working directly for the employer, under the supervision of the Pinkertons or other private security forces.

In the end, the vastly outnumbered Pinkertons surrendered. More than a dozen people were left dead ( 3 Pinkertons and 6 steelworkers) and others were wounded. On November 20, the strike officially ended and Carnegie achieved control over his labor force again.

The fallout from the melee crippled the steel union, but it also branded the Pinkertons as “hired thugs,” leading several states to pass laws banning the use of outside guards in labor disputes. In the aftermath, political leaders and employers decided that a new, more legitimate-seeming system of labor management was needed, to be paid for out of the public coffers. The result was the creation of the Pennsylvania State Police in 1905.

While Frick’s hardline stance ultimately led to the demise of the union the Pinkertons role in the conflict helped cement their reputation as the paramilitary wing of big business. Anarchists would later unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Frick. The broken union in Homestead eventually joined the United Steel Workers, formed later in 1942. The Homestead Strike still stands out in history as an example of how difficult it remains for unions to contest the power of management and secure the interests of workers.

“Pinkerton’s Landing Bridge,” as it is now known, is the nickname given to the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad Bridge at Munhall. The bridge crosses the Monongahela River between Muhall, Pa and Rankin, Pa.

Other Pinkerton confrontations that are noteworthy include the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Battle of Blair Mountain (West Virginia) in 1921.

Pinkertons Inspired the Term “Private Eye”

The Pinkerton agency first made its name in the late-1850s for hunting down outlaws and providing private security for railroads. As the company’s profile grew, its iconic logo—a large, unblinking eye accompanied by the slogan “We Never Sleep”—gave rise to the term “private eye” as a nickname for detectives.

Pinkertons Hired the Nation’s First Female Detective

In 1856, 23-year-old widow Kate Warne walked into Pinkerton’s Chicago office and requested a job as a detective. Allan Pinkerton was hesitant to hire a female investigator, but he gave in after Warne convinced him that she could “worm out secrets in many places to which it was impossible for male detectives to gain access.” True to her word, Warne proved to be an expert at working undercover, once busting a thief by cozying up to his wife and convincing her to reveal the location of the loot. During another case, she got a suspect to feed her crucial information by disguising herself as a fortune-teller. Pinkerton would later list Warne as one of the best investigators he ever hired. Following her death in 1868, he even had her buried in his family plot.

Molly Maguires

In the 1870s, Franklin B. Gowen, President of the Philadelphia Reading Railroad, hired the agency to “investigate” its labor unions in the company’s mines. When mine owners and managers docked pay and benefits, some Mollies, as they were known to locals, killed whoever stood in the Irish miner’s way of a better life. A Pinkerton agent, James McParland, using the alias “James McKenna”, infiltrated the Molly Maguires, a 19th-century secret-society of mainly Irish-American coal miners, which ultimately lead to the downfall of the labor organization.

Molly Maguires

Pinkertons May Have Foiled a Presidential Assassination Attempt

Shortly before Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration in March 1861, Allan Pinkerton traveled to Baltimore on a mission for a railroad company. He was investigating rumors that Southern sympathizers might sabotage the rail lines to Washington, D.C., but while gathering undercover intelligence, he learned that a secret cabal also planned to assassinate Lincoln, who was at that time on a whistle-stop tour, as he switched trains in Baltimore on his way to the capital.

Pinkerton tracked down the president-elect and informed him of the alleged plot. With the help of Kate Warne and several other agents, he then arranged for Lincoln to secretly board an overnight train and pass through Baltimore several hours ahead of his published schedule. Pinkerton operatives also cut telegraph lines to ensure the conspirators couldn’t communicate with one another, and Warne had Lincoln pose as her invalid brother to cover up his identity. The president-elect arrived safely in Washington the next morning, but his decision to skirt through Baltimore saw him lampooned and labeled a coward in the press. Meanwhile, none of the would-be assassins was ever arrested, leading some historians to conclude that the threat may have been exaggerated or even invented by Pinkerton.

Pinkertons Spied for the Union Army During the Civil War

Allan Pinkerton was a staunch abolitionist and Union man, and during the Civil War, he organized a secret intelligence service for General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Operating under the name E.J. Allen, Pinkerton set up spy rings behind enemy lines and infiltrated southern sympathizer groups in the North. He even had agents interview escaped slaves to glean information about the Confederacy.

Pinkertons Created One of the First Criminal Databases

One of the many ways the Pinkertons revolutionized law enforcement was with their so-called “Rogues’ Gallery,” a collection of mug shots and case histories that the agency used to research and keep track of wanted men. Along with noting suspects’ distinguishing marks and scars, agents also collected newspaper clippings and generated rap sheets detailing their previous arrests, known associates and areas of expertise. A more sophisticated criminal library wouldn’t be assembled until the early 20th century and the birth of the FBI.

Pinkerton Detectives guarding the coffin of actress Marilyn Monroe, 1962

Modern Era

Due to its history of conflicts with labor unions, the name Pinkerton continues to evoke negative associations. Pinkertons evolved over the course of time and diversified from labor spying following revelations publicized by the La Follette Committee hearings in 1937. The firm’s criminal detection work likewise suffered from the police modernization movement. Calls for increased police professionalization saw the rise of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the bolstering of detective services offered by local police forces. All of these developments caused the Pinkertons influence to diminish over time.

In 1999, the company was bought by Securitas AB, a Swedish security company. This was followed by the acquisition of a longtime Pinkerton rival, the William J. Burns Detective Agency, to create an additional division, Securitas Security Services USA. The company thus continues to live on as a private security firm and guard service, however, it operates under the shortened name “Pinkerton.”

So What Do We Do Now? How Do We Fix the Police?

Vitale argues we need to rethink the role of policing and to reduce the ways in which police are used in our society. Does that mean we should eliminate police forces altogether? Probably not. History doesn’t have to be the template from which we base our present operations. We can and must find a way to chart a path so that we can realize a more progressive form of policing that serves our modern society; one that is not based on reinforcing and exacerbating existing social inequalities.

As Vitale argues, we need people who are trained to deal with our most vulnerable and difficult populations; people who understand their point of view and who take seriously their role to help them, not just arrest, restrain and control them.

Beyond that, we need to deal with the manifest social problems that derive from maintaining a society in which large parts of the population are considered surplus or undeserving.

Sources

“The Myth of Liberal Policing,” by Alex Vitale, 2017.

The End of Policing, by Alex Vitale, 2017.

“10 Things You May Not Know About the Pinkertons,” by Evan Andrews, 2015