Most Americans that have lived a middle-class life have no idea how people living in poverty negotiate their lives. There is a tendency to think of “the poor” in the abstract – a group of unwashed masses who seem to always live in inner cities or trailer parks. When poor people are thought of as poor people as people at all, they are often referred to using terms like “slackers,” “losers,” “drop-outs” “takers” – the people who “just don’t want to work.”

Even when they do work, they don’t work the “right” jobs. They work in what are thought to be “unskilled” traditional “teenager jobs” – retail sales clerks, gas station attendants, McDonald’s counter work, etc. And so the thinking goes, these are not the kind of jobs that serious people apply themselves to. People who have serious intentions to one day raise a family graduate from these jobs: they go to college, aspire to better jobs, and move up in the world. If poor people could simply grasp this common wisdom, they wouldn’t be doing what they’re doing AND they wouldn’t be poor. How many times have you thought this?

What you think about poor people and whether or not you believe we should help them probably boils down to your take on a single question: why don’t poor people work? As it turns out, there’s research on that!

But before we get into the research, let’s take a moment to consider how much one’s personal beliefs in this regard are in no small way influenced by their social ecology (family, friends, and neighborhoods where you grew up) and personal experiences. These traditional sources of knowledge are handed down and form a repository of what we call “common wisdom.” This kind of thinking is the opposite of critically reasoned, empirically informed, rational thinking. But it feels good because you get to share the views of everyone around you – confirmation bias – and so why change?

Research shows that the kinds of things your friends and family say about poor people are the primary sources of influence when it comes to what you believe about poor people – far more than any knowledge based on research and data. When “beliefs” and “facts” don’t line up very well, the result is “cognitive dissonance.” In the case of politicians and policy makers, rather than do the heavy lifting required to explain contradictions and misunderstanding, they often take the easy way out (they go with which way the political wind is blowing). By validating constituent beliefs (even when those beliefs are misinformed and/or wrong), people feel gratified and vote accordingly. Ultimately, the public is not well-served because legislators aren’t fixing social problems. Instead, they’re playing a game of crass politics calibrated to “what will get me re-elected?”

In addition to the influence of friends and family, what you think about “the poors” is probably also shaped by your political ideology. Thus it has been documented that people who identify as liberal will more often attribute poverty to social factors, like discrimination, whereas those who identify with social conservativism will more often point to individual choices (bad ones) that people make and subsequent failure to assume personal responsibility for their fate.

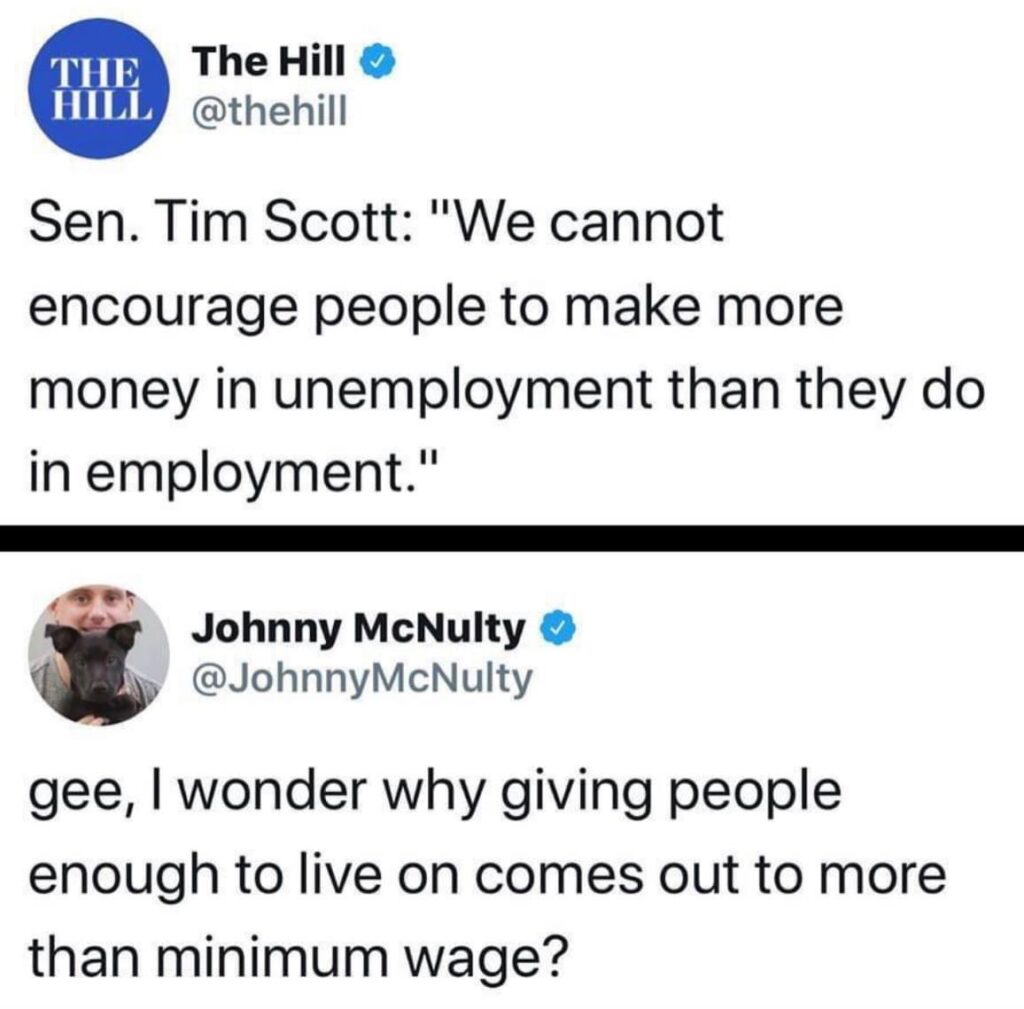

Political party ID also has a major impact on how people understand unemployment, welfare benefits, food stamps, etc. People tend to argue that short term unemployment, particularly as it impacts middle-class families, naturally fluctuates with the job market. Long-term unemployment, however, is thought to be more influenced by cultural forces and not the market – a “culture of poverty” associated with bad behavior. This sentiment reflects a simmering resentment that the poor could work if they wanted to, but a culture of sloth combined with a generous social safety net coddles them and acts as a disincentive to work. Put another way, political conservatives argue that government programs designed to alleviate poverty are doing the opposite: they encourage poor people to not work.

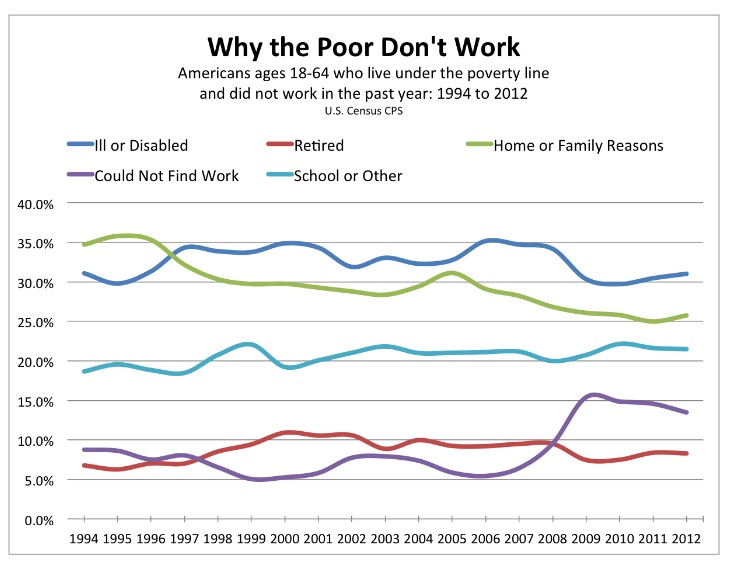

A key data point cited to support this belief in individual sloth comes from the Census. Every year, the Census Bureau asks unemployed Americans why they’re not working. And traditionally, it is a small percentage of poor adults who say it’s because they can’t find employment. Census figures, however, can be interpreted in a number of different ways. Taking the Census figures at face value, there are a few lessons are in order.

First, it is helpful to think of poverty and unemployment as not only a function of individual behavior, but also as a function of history and social context

The recession in 2008 changed poverty in many respects. From that point forward, we find more of the non-working poor are claiming they cannot find a job than at any point in the past two decades. Of course, unemployment rates fluctuate. However, this shouldn’t be much of a surprise. What is interesting is that when researchers took a closer look, they found that a lot of poor who “choose” not to work aren’t necessarily doing so out of laziness (the stereotype). Rather, it is due to other personal obligations: they’re trying to take care of relatives, they’re ill, or they’re attempting to make their way through school.

Poor people also tend to work jobs that are physically taxing; jobs that require a lot of lifting and standing. This puts them at a higher risk for suffering from disabling injuries. Chronic pain and reliance on pain medication opens the door to addiction for many of them, which leaves them in progressively increasingly worse situation.

The research also notes there are big differences with regard to gender. Women are more likely than men to cite family reasons for not working; men are more likely to cite their inability to find a job (Weissman).

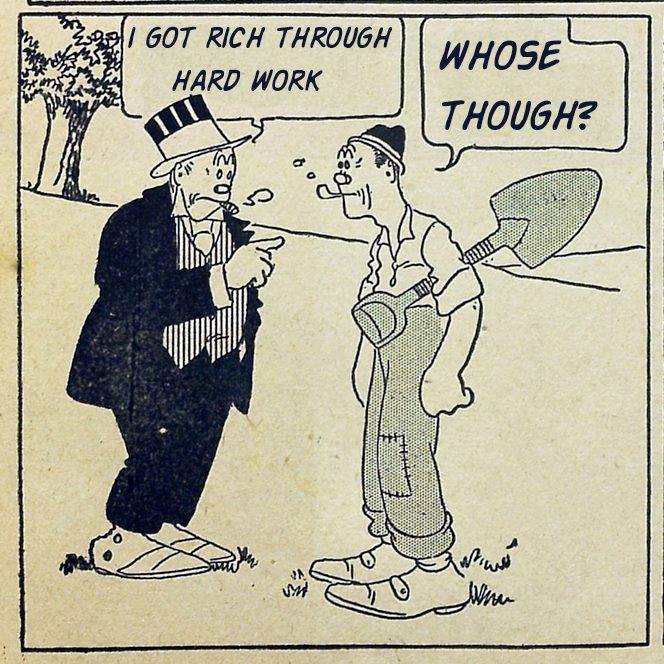

Setting aside those people who don’t work for a moment, let’s take a look at the people who are working. Most of the poor who can work are working. The problem is wages remain low. Fifty-seven percent of the families below the poverty line in the U.S. are working families, working at jobs that just don’t pay enough to support them and their families.

Ask yourself: is it okay to pay people poverty wages (wages that can’t feed or support their families) when they are doing work that is socially necessary? Is service work the new “plantation” of the 21st century?

So it’s not that the poor want to work like burger-flipping teenagers or that they’re lazy; they often do back-breaking and thankless work and work more than one job. Keep in mind, many of these low paid “unskilled” jobs fulfill important social needs. Caregiving and working in restaurants are are very much in demand from U.S. consumers. The real problem is that wages are too low.

Researchers have recently started to focus their efforts on understanding poor working people and what kind of work do they do. And this is what they have discovered. Occupationally, poor employed people tend to be childcare workers, home health care workers, janitors, house cleaners, lawn-service workers, bus drivers, hospital aides, waitresses, nursing home employees, security guards, cafeteria workers, and retail cashiers.

Sadly, not only do we expect them to do these incredibly important jobs, we expect them to also live in poverty while they do it. And we scream bloody murder if they don’t want to do the jobs that we all agree are thankless, difficult, and low-paid.

In should not need to be said (but it does) – these are not stupid lazy people performing unimportant jobs. They are, in fact, precisely the kinds of jobs that help make society work for everyone else; they enable other people to go to their jobs and earn a living. Nonetheless, people who perform this kind of work are summarily written off as socially unworthy, shiftless, lazy, and even stupid for making a “bad” career choice.

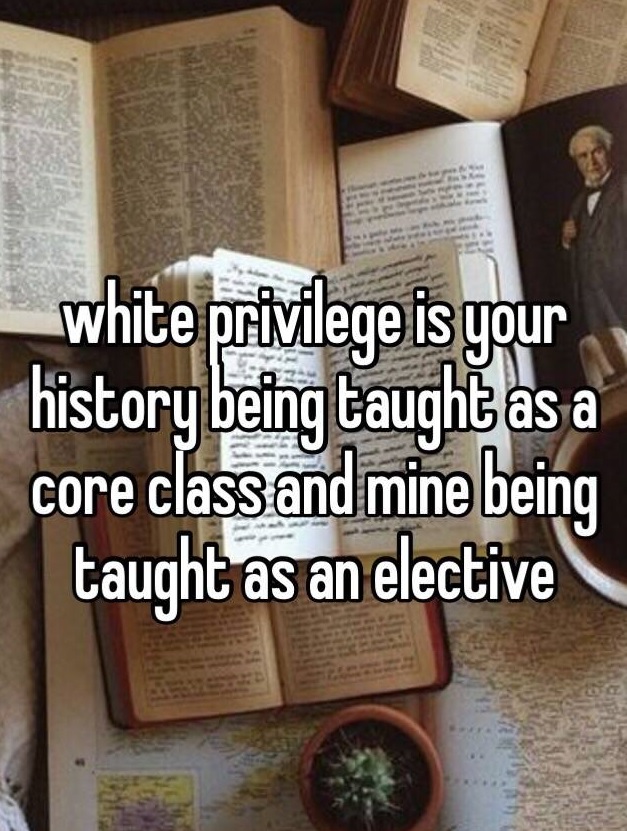

History

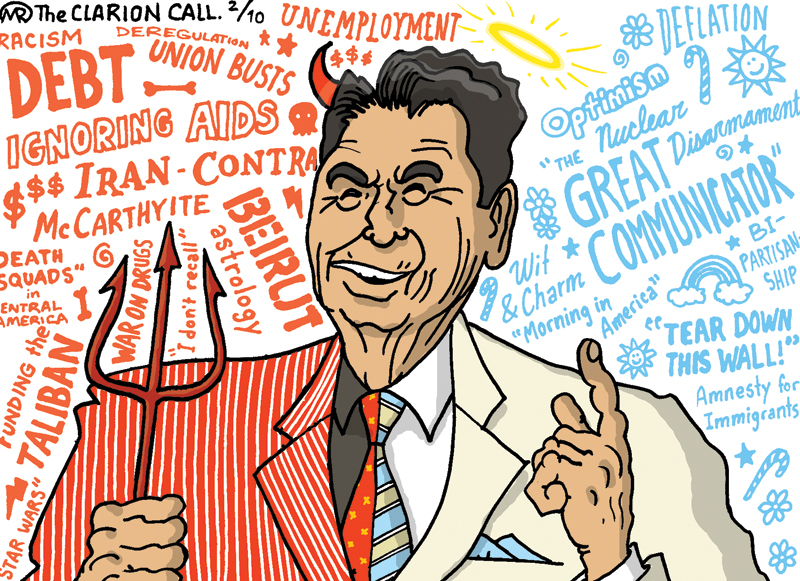

For more than 30 years, politicians in the United States have worked to systematically undermine the poorest Americans. How did they do it? They prioritized tax cuts for the wealthy and engaged in unchecked military spending, all the while convincing average Americans (who don’t benefit from the tax cuts and military spending) that their way of life was in danger if these things were not accomplished. Both of the major political parties in the U.S. have done this to different degrees, with some more than others engaging in fear-mongering and the provoking of racial antipathy to get it done.

Put another way, they discovered that they way to get Americans to support their agenda was to push the narrative that the economy was being hurt by welfare slackers, unrestrained criminality, teen pregnancy, affirmative action recipients, and “illegal alien” criminal immigrants.

This narrative script still holds sway over our current politics. Now more than ever, as even middle class Americans are feeling the pressure. The mindset of middle class people tends to be one that is aspirationally focused: that is, they look up the economic ladder and aim to find ways to share common cause with wealthy Americans, whose ranks they hope to join if the “work real hard.” They seek proximity to wealth through their jobs and their consumption habits. Part of doing so means they must also engage in efforts to socially distance themselves from the poor – this helps them to demonstrate by way of belief and personal practice that “I am not like them.”

In our recent history, attacks on the former President Barak Obama fit seamlessly into these developments. He was accused of not being American through a politics of fear that tries to generate suspicion of “enemy” others who are “not like us.” In the end, even Obama capitulated in many respects, advocating for social and monetary policies that benefitted banks more than they helped poor people.

Consequently, any attempts to fix social problems like poverty and social welfare programs through responsible governance (i.e. effective policy making) have been largely defeated by politicians who employ cynical politics to manipulate voters and by the voters themselves who have allowed their emotions to be captured by this process.

The Underclass

Academic poverty studies are prolific. In the current era, Columbia University sociologist Herb Gans argued in his 1995 book “The War Against the Poor” that the label “underclass,” a term that we can apply to a variety of people—working poor, welfare recipients, teenage mothers, drug addicts, and the homeless, reduced members of these groups into to a single condemned “untouchable” class. As a result, poor people became feared and despised by the rest of society.

This label has proved to be powerful and long-lasting. Perhaps the most pernicious effect is how it effectively transformed the individual’s experience of being in poverty into what academics have referred to as a spoiled identity – an identity marked by personal failing and, in particular, a failure to make good choices in life.

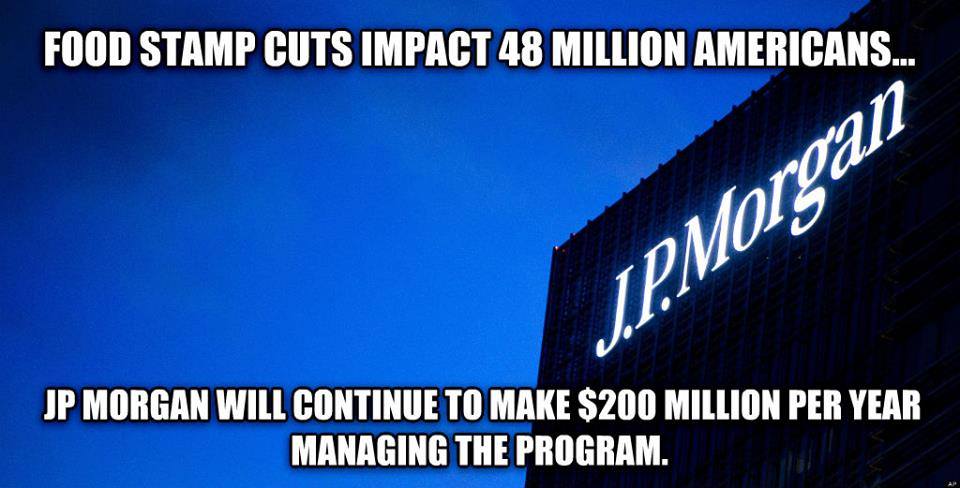

On the policy front, all social welfare policies, but especially those popularly referred to as “food stamps,” have been effectively stigmatized and rendered highly controversial in the United States.

The entrenchment of negative stereotypes about poor people has helped political contrarians among others to call into question FDR’s legacy “Great Society” programs along with other civil rights era policies formulated during the 1960’s and 1970’s. This has been greatly aided by the efforts of those in the political pundit class (big media mouthpieces paid to carry water for they wealthy who pay them) to criticize “welfare entitlements.” In recent years, the attacks have become vitriolic and relentless.

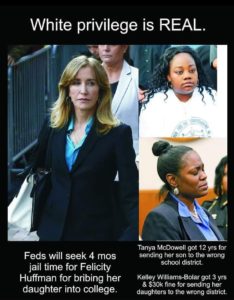

In what amounts to a piling-on effect, the efforts of politicians and the traditional media have been amplified a thousand times by the echo chamber of digital and social media. In social media, the ultimate currency is the “click.” In light of this, social media platforms have become notorious for click-bait images that provoke outrage. The promotion of negative cultural stereotypes has become valuable to efforts to drive clicks and thus revenue. Social media effectively monetizes anger and outrage.

Reagan’s Welfare Queen

There is no more significant political figure in this history than Ronald Reagan, who in the late 1970’s, during a period of significant economic adjustment, restructuring, and de-industrialization in the United States, managed to divert people’s attention away from larger macroeconomic issues by exploiting white working class fears about the expansion of social welfare benefits. For local reference, this is the same period in time during which many of the steel mills in Pittsburgh began to falter and good jobs started to become scarce.

The “Welfare Queen” of Reagan’s speeches was intended to provoke outrage; it was an affront to the political philosophy of personal responsibility and rugged individualism espoused by “hard working people” (racially coded white people), who were experiencing considerable economic pain as a direct result of his administration’s economic policies.

Reagan relied on what social psychologists refer to as “narrative scripts,” His 1976 campaign trail stump speech included the story of a woman from Chicago’s South Side arrested for welfare fraud. According to Reagan:

“She has 80 names, 30 addresses, 12 Social Security cards and is collecting veteran’s benefits on four non-existing deceased husbands. And she is collecting Social Security on her cards. She’s got Medicaid, getting food stamps, and she is collecting welfare under each of her names.”

The storyline proved to be extraordinarily effective for its ability to tap into entrenched race, class, and gender stereotypes dating back to the American Civil War about African American women (uncontrolled sexual appetites) and African-American work ethic (laziness).

Three falsehoods emerge from the “Welfare Queen” narrative:

1) most people living in poverty are women (they are children and the elderly)

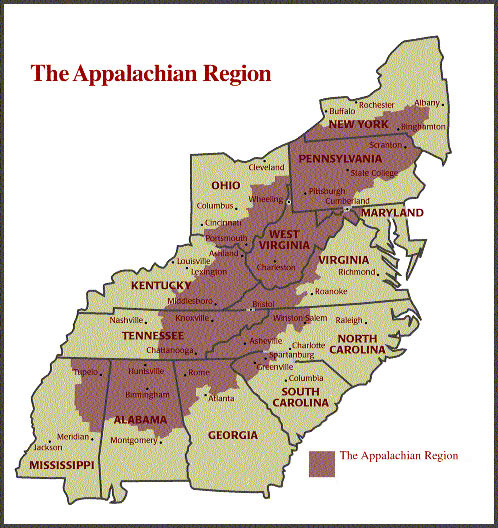

2) most people on public assistance are urban (they are rural)

3) most people on public assistance are black (they are white).

None of these narratives hold up to research scrutiny, yet they prevail today and are perhaps as powerful as ever.

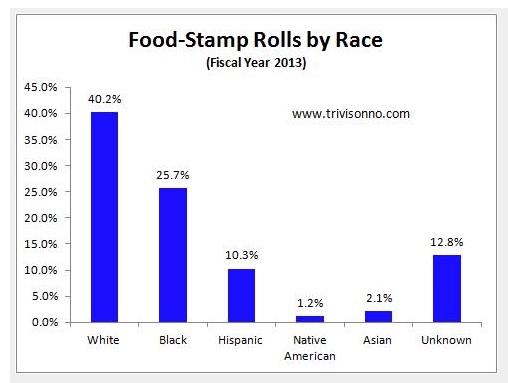

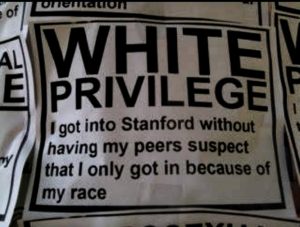

Who Is on Welfare?

Though many are shocked by this, whites are by far the biggest beneficiaries when it comes to government safety-net programs like the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), commonly referred to using the short term “welfare.” If we were to break this down further, the largest sub-group of people who are presently living in poverty are white children followed by the elderly. And while black women represent more than one-third of the total number of women on welfare, data shows they account for only ten percent of the total number of welfare recipients.

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program is the program that has most frequently been called welfare; it was created in the famous “welfare reform act” of 1996. As a result of that reform, the program that exists today is much smaller than its predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), which only served 2.7 million people in 2016.

Of course, many of these facts run counter-intuitive to what many people have come to believe as social fact. As a new HuffPost/YouGov survey shows, the American public has wildly distorted views about which groups are the largest beneficiaries of government programs.

Fifty-nine percent of Americans say either that most welfare recipients are black, or that welfare recipiency is about the same among black and white people. Only 21 percent correctly said there are more white than black food stamp recipients.

Additionally, when survey respondents were asked to estimate who receives welfare, they provided answers that tracked closely to their estimation of who also gets food stamps. Elizabeth Lower-Basch, a senior analyst with the Center for Law and Social Policy, says that people significantly overestimate the number of black Americans benefiting from the largest programs. She says “It’s not surprising because we all know people’s images of public benefits is driven by stereotype” (Delaney and Edwards-Levy, 2018).

In a similar fashion, the urban vs. rural dichotomy is also not sustained. Rural people receive benefits in far greater numbers than urban people. And here again, most rural people receiving public assistance are white. These social dynamics are visually rendered in both the map and table below. The map below shows the geographic distribution of food stamp recipients in the United States (dark shaded states have more people collecting benefits); the table under the map illustrates the racial identification of food stamp (SNAP) recipients.

Let’s use a sociological intersectional analysis to look at how race, social class, region, and education all work together and tell us something about who is on welfare.

Black is Shorthand for Poor

What does poverty look like in America? Judging by how it’s portrayed in the media, it looks black.

That’s the conclusion of a new study by Bas W. van Doorn, a professor of political science at the College of Wooster, in Ohio, which examined 474 stories about poverty published in Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News and World Report between 1992 and 2010. In the images that ran alongside those stories in print, black people were overrepresented, appearing in a little more than half of the images, even though they made up only a quarter of people below the poverty line during that time span. Hispanic people, who account for 23 percent of America’s poor, were significantly under-represented in the images, appearing in 13.7 percent of them (Pinsker).

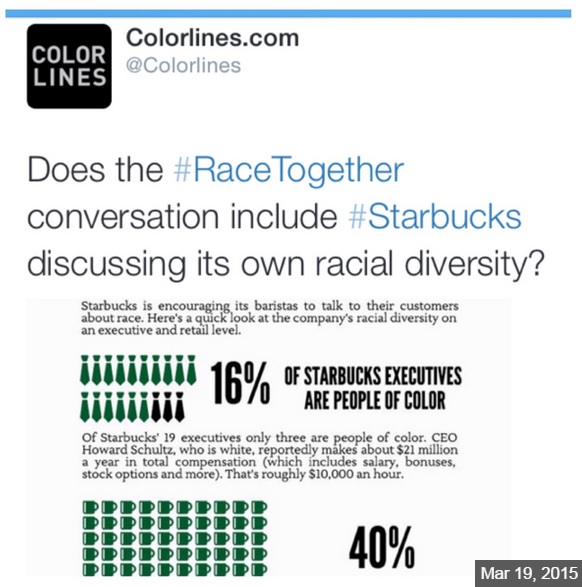

According to the USDA in their report for fiscal year 2013, 40% of aid recipients are white and 26% are black. While the food stamp program has one of the lowest rates of abuse than any other welfare program, many people find it easy to buy into the misconception that it’s the “lazy blacks” who account for the fraud woes of government assistance. Here again, the data above refute these narratives and common stereotypes.

How many people – be honest now – are surprised to learn that the biggest recipients of federal poverty-reduction programs are working-class white people? This is a widely documented fact, even if it is not commonly understood.

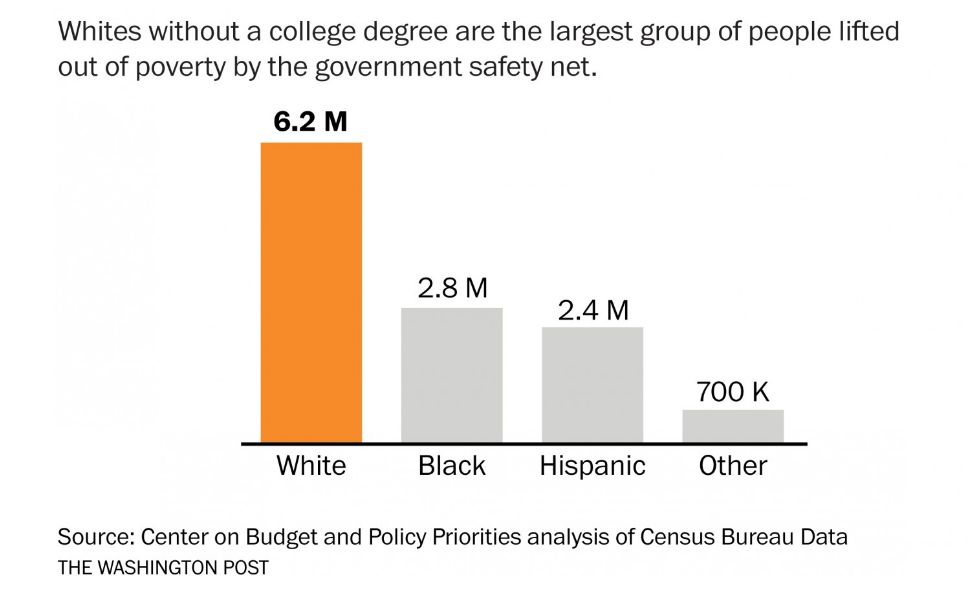

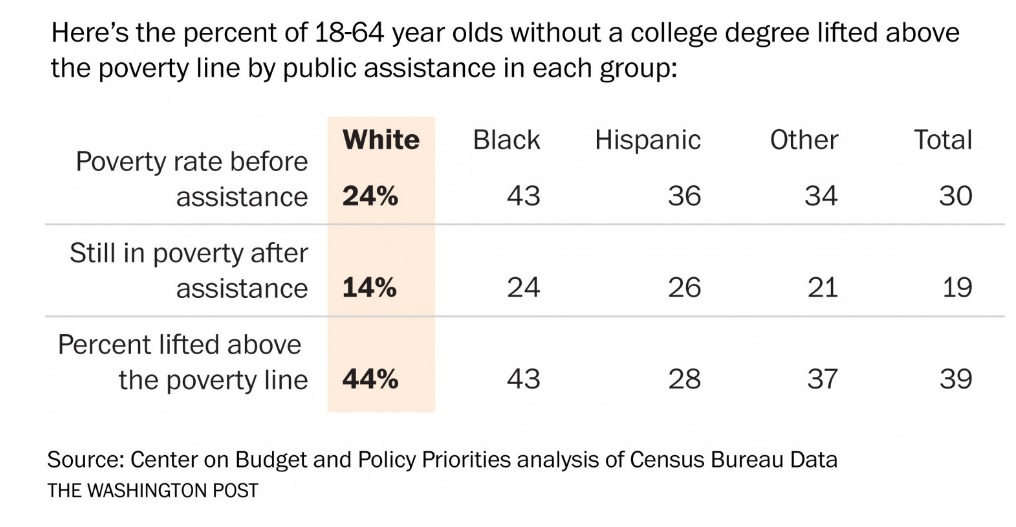

White people without a college degree ages 18 to 64 are the largest class of adults lifted out of poverty by such programs, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (progressive policy think tank). Their 2017 report. based on U.S. census data stated that 6.2 million working-age whites were lifted above the poverty line in 2014 compared to 2.8 million blacks and 2.4 million Hispanics.

So the question remains – why is this not more widely understood? Unfortunately, the answer relates back to the enduring power of stereotypes and prejudices, which people tend to inherit when they believe traditional sources or trust “common knowledge” (i.e. friends and family). That this occurs testifies to the power of traditional narratives to act as a cultural shortcut – this help us fill in the gaps where our actual knowledge may be lacking.

Consequently, even though blacks and Hispanics have substantially higher rates of poverty (both in numbers and as a proportion of their respective social groups), whites receive the most benefits and populate the welfare rolls in higher numbers (see a new study published by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities).

One of the significant study findings, in this particular case, was that the numbers do not simply reflect the fact that there are more white people in the country; they demonstrate a good deal more than this – that the percentage of poor whites lifted out of poverty by government safety-net programs is substantially higher compared to all other social groups – 44 percent of whites, compared to 35 percent of otherwise poor minorities ( CBPP study).

According to Isaac Shapiro, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (one of the report’s authors):

According to Isaac Shapiro, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (one of the report’s authors):

“There is a perception out there that the safety net is only for minorities. While it’s very important to minorities because they have higher poverty rates and face barriers that lead to lower earnings, it’s also quite important to whites, particularly the white working class.”

Research on Stereotypes of Poverty and Welfare

Researchers like Princeton Political Scientist Martin Gilens have documented how negative media portrayals of African Americans contribute to the perception that there are more blacks than whites who live in poverty and “take” benefits.

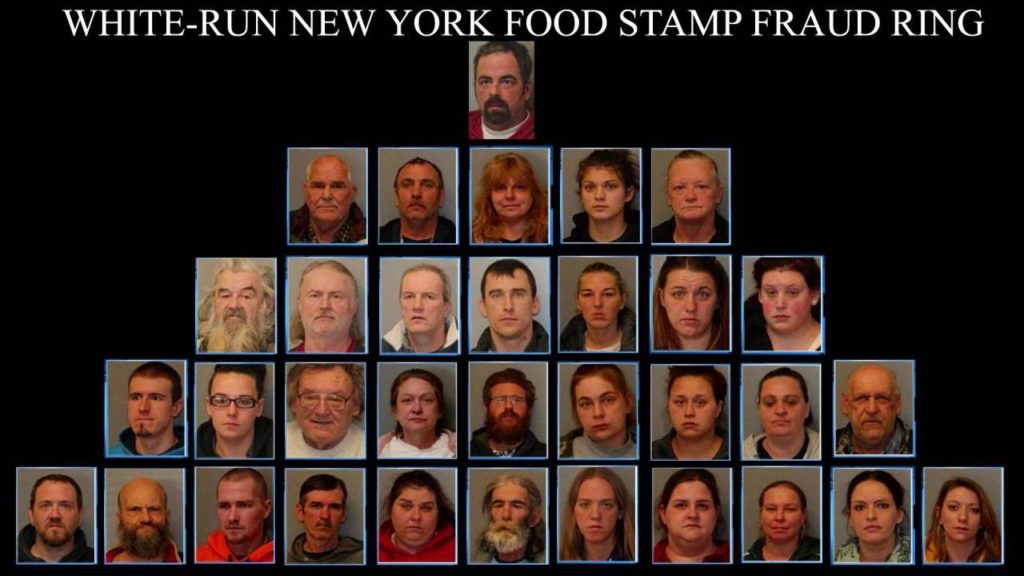

A Feb 2015 incident in Brushton New York illustrates that contrary to these stereotypes, the opposite case is often the reality. Police officers in Brushton arrested 30 people in connection with fraud. They were arrested for using their food stamp cards in a manner that was against the law. All were white.

Racial stereotypes not only harm the people they are intended to malign, such views also contribute to the under-estimating of the actual number of poor whites who live under these circumstances. Once entrenched, these narrative scripts can be particularly difficult to dislodge due to a phenomenon called “confirmation bias”(or confirmatory bias)–people incorporate the unsupported narratives into their belief systems and interpret ALL subsequent new information in ways that refer back to/confirm their pre-conceived beliefs.

Confirmation bias is demonstrated when decision makers actively seek out and assign greater emphasis to information/evidence that supports their pre-existing beliefs, while at the same time they conveniently ignore evidence that contradicts or undermines those beliefs. Some people (including your professor) refer to this biased selection process as “cherry picking.”

The Experiment

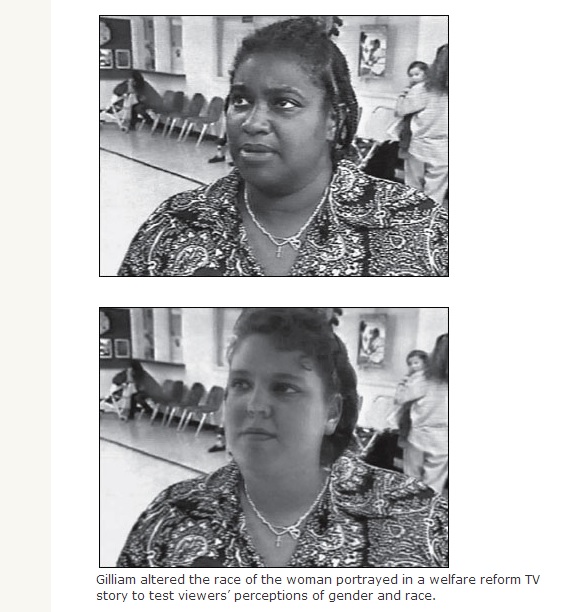

To prove the pernicious effect of Reagan’s stereotypical “Welfare Queen,” Franklin D. Gilliam, Jr., a professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Los Angeles, conducted an experiment. Gilliam constructed a series of television news stories about the impact of welfare reform that featured a woman named Rhonda Germaine.

In his report, Gilliam had this to say:

“One of the more controversial issues on the American domestic agenda is social welfare policy. The near unanimity surrounding the “Great Society” programs and policies of the mid-to-late 1960’s has given way to discord and dissonance. Conservative thinkers and politicians first launched attacks on the “welfare state” in the aftermath of the civil rights disturbances of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. While Barry Goldwater, George Wallace and Richard Nixon charted the course, Ronald Reagan encapsulated the white majority’s growing unease with the perceived expansion of the social welfare apparatus. In particular, Reagan was able to forge a successful top-down coalition between big business and disaffected white working-class voters. The intellectual core of the movement was a well-funded punditry class that offered a theoretical vision for the “New Right.”

While this perspective touched on the cornerstones of American political philosophy individualism and egalitarianism it also carried with it a heavy undercurrent of gender and racial politics. In the midst of this evolving political landscape on which new debates about welfare were taking place, the news media played and continues to play a critical role in the public’s understanding of what “welfare” is and what it ought to be. According to Gilliam:

Utilizing a novel experimental design, I wanted to examine the impact of media portrayals of the “welfare queen” (Reagan’s iconic representation of the African-American welfare experience) on white people’s attitudes about welfare policy, race and gender. My assumption going into this study was that the notion of the welfare queen had taken on the status of common knowledge, or what is known as a “narrative script.”

The welfare queen script has two key components: 1) welfare recipients are disproportionately women; and 2) women on welfare are disproportionately African-American.

What I discovered is that among white subjects, exposure to these script elements reduced support for various welfare programs, increased stereotyping of African-Americans, and heightened support for maintaining traditional gender roles. And these findings have implications both for the practice of journalism and the development of constructive relations across the lines of race and gender.”

How it Worked

Study participants, who differed on the basis of race and gender, were randomly assigned to one of four groups. Each group watched one of four different news stories. The first group watched the news story with Rhonda cast as a white woman. The second group saw a story that depicted Rhonda as an African-American woman. The third group watched the story without seeing a visual representation of Rhonda. The last group, a control group, did not watch any TV stories about welfare. At the end of the videotape, study participants were given a lengthy questionnaire that probed their political and social views.

Study Findings

The welfare queen script assumed the status of common knowledge. When white subjects were asked to recall what they had seen in the newscasts, nearly 80 percent of them accurately recalled the race of the African-American Rhonda; less than 50 percent recalled seeing the white Rhonda.

Subjects who recorded the most “liberal” views about gender roles turned out to express the most hostility to blacks after they were exposed to white Rhonda. In other words, gender-liberal white participants who were shown the image of the African American woman were more likely to respond that they opposed welfare spending; they attributed “individuals” making bad decisions as the main cause of social problems and endorsed negative characterizations of African-Americans. This tendency was most pronounced among women respondents.

Social Welfare and Social Media

So now that we’ve looked at some research and data, take a look at the following video and see if you can pick up on the cultural stereotypes and narrative scripts that distinguish not only this v-logger’s thinking, but maybe even the thinking of some people you know (or you?):

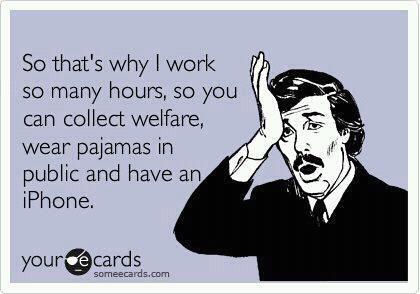

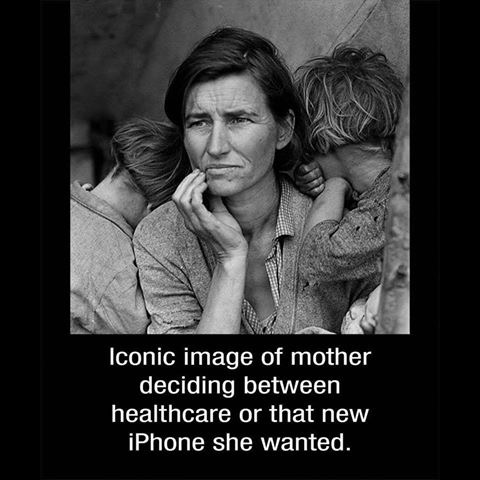

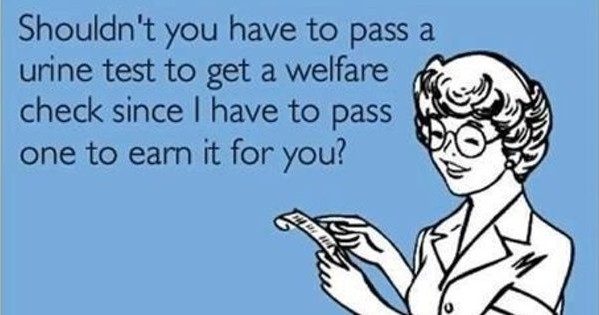

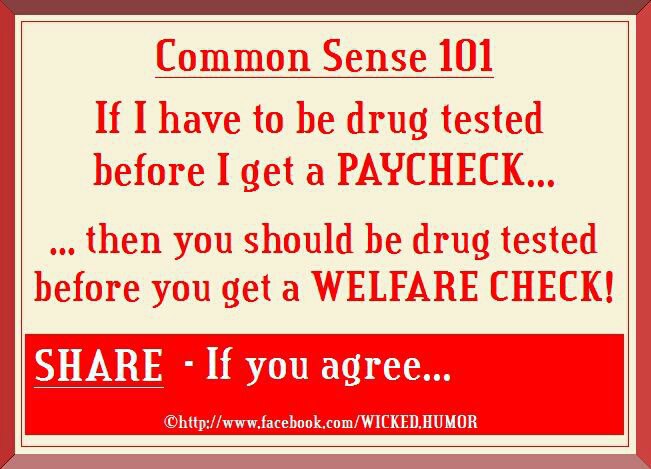

The next two images might be familiar to you, if only because they tend to constantly recycle themselves through Facebook and other social media. They are shared because they are assumed to be funny, but only if you are “in” on the joke, which in this case is that poor people are not so poor as you think. Rather, they are apparently living the high life, taking advantage of the system, while us poor dupes work hard to pay for their care-free and easily acquired lifestyle.

Both images imply that people who are not working/collecting benefits should not have smartphones. Odd thinking when we consider how helpful having a smartphone might be for someone waiting for an employer to call them for a job that would potentially get them OFF welfare. It’s as if the thought never occurs to people that welfare recipients might have previously been employed; that prior to their job loss, they might have had sufficient resources that would let them own things like smart phones, cars, and nice clothing. Is the expectation here that people should sell off all of their personal possessions in the event of sudden unemployment?

Social media, as demonstrated here, traffics in a cultural logic that, while not explicitly stated, nonetheless, assumes a set of “unwritten” rules for welfare benefit /”food stamp” recipients:

1) if you lose a job and apply for public assistance, you should sell any and all electronics and luxury goods you were fortunate enough to have possessed prior to your job loss;

2) don’t dress/present yourself too well in public, since this demonstrates you don’t really need financial assistance;

3) don’t dress/present too poorly, because this demonstrates your general unworthiness and constitutes even more proof that you shouldn’t be receiving welfare benefits

By now the contradictions should be obvious. In the end, it’s pretty hard for anyone who is poor to win here. The assumption is that in order to be seen as a “good” poor person” you must divest yourself of all personal possessions (even if you acquired them when times were good); you must also take care to look properly disheveled…but not too much. Striking the right balance is the key. Thus, it is only by walking this fine line that you can escape public judgment and ridicule.

Social media shaming works hand in hand with real-life shaming. In recent times, a number of high-profile videos have surfaced, which show what are almost always white identified people being verbally abusive and sometimes attacking poor minority people for doing things like demonstrating that they are bilingual (they can speak Spanish as well as English whenever they choose). Many low-wage people and families are subject to getting dirty looks from fellow shoppers for using food stamps in the checkout line (something that, as any cashier will tell you, a lot of working people, who are fully employed in low wage jobs, use the small food supplement to help make ends meet).

iPhone & Refrigerator Shaming Continued

Former Utah State Representative, Jason Chaffetz, once told a CNN television reporter that Americans might have to decide between owning a smartphone and having health insurance. In other words, Americans are going to have to cut back on modern “luxuries” like a phone if they want to be able to afford health insurance.

According to Chaffetz: “And so maybe rather than getting that new iPhone that they just love and they want to go spend hundreds of dollars on that, maybe they should invest that in their own healthcare.”

While Chaffetz was justifiably made fun of for his comparison (people pointed out that a year’s worth of health care would roughly equal 23 iPhone 7 Pluses in price), he was merely giving voice to what is again a commonly held belief – that poverty in the United States is the result of laziness, immorality, irresponsibility, and poor individual choices.

Another analogy was featured in a Fox News story. Anchor Stuart Varney talked about how “lucky” poor people are to have things like refrigerators.

Once more, we see evidence of a simplified logic: that if people engaged in better decision making — if they worked harder, stayed in school, got married, didn’t have children they couldn’t afford, spent what money they had more wisely and saved more — then they wouldn’t be poor. This deeply entrenched narrative continues to shape public thinking and beliefs about poor people in general. Further, it influences the thinking of government policy makers on BOTH sides of the two polarized sides of the political spectrum, who perhaps more than other people, should be incorporating findings published by research if they are truly committed to solving social problems.

Welfare Reform

While this flawed thinking owes a debt to Reagan, we find it similarly embedded deep within the logic of President Bill Clinton’s 1996 signature welfare restructuring law – the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA). This was the logic that drove efforts to impose work requirements on Medicaid recipients, to drug-test people collecting SNAP benefits and/or unemployment insurance, and to in some circumstances prevent aid recipients from buying steak and lobster.

Social media images, memes and the like, are not trivial. Because of their ubiquity and appeal to humor, they serve as powerful framing mechanisms for non-critical ways of thinking about who is poor and deserving of help – the worthy poor – as opposed to people deemed not “poor enough” and thus not deserving of help.

Although the images are not explicitly racialized, research like that conducted by both Gilens and Gilliam demonstrates that any expressed agreement or support for/against benefits are likely to be more reflective of “beliefs” that draw from gender/race/class stereotypes – not understanding that is based on data and evidence derived from research.

The images, in terms of their effect, do nothing to “inform” and promote understanding; rather, they entertain while they at the same time stoke the fires of conflict and misunderstanding, and thereby perpetuate resentment of disadvantaged groups.

Consequently, no matter what poor people do (or not do), the poor in the United States are treated like social outcasts and criminals. This is not to say that poor people don’t make bad choices sometimes. Of course they do in some cases. Research, however, demonstrates that it is more likely that the structural system of capitalism has a far greater impact on how earning opportunity is organized, who has access to it, and who will ultimately have to struggle more than others.

Because all of this is complicated, most people would rather argue that the system is working and that it’s individual people who are solely to blame for the cause of their own poverty.

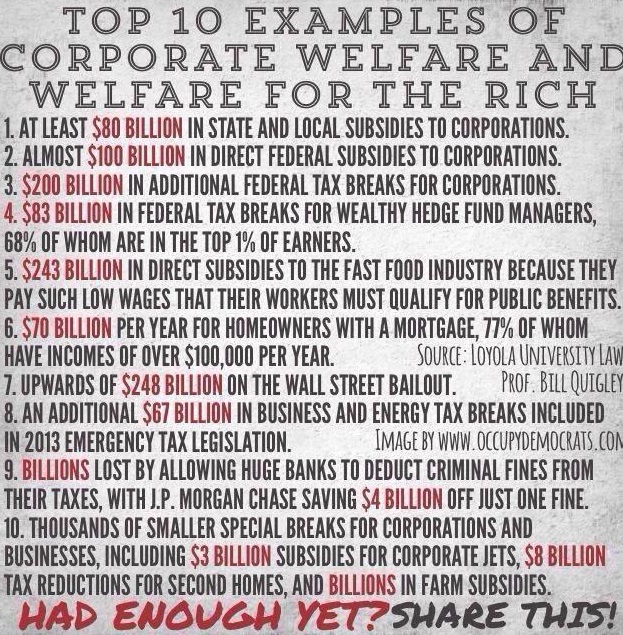

The Politics of Visibility

Working class people – people who are only slightly more successful than the working poor people located just below them on the social class ladder – don’t come anywhere close to getting any of the government giveaways that corporate shareholders get at places like Amazon, Google, and Boeing, or for that matter that typically wealthy people get. Their social status/social location make it difficult for them to “see” how wealthy people benefit from the system – specifically, from infinitely more generous tax policy on things like capital gains (taxed lower than wages from labor), government subsidies, and arcane accounting maneuvers like carried interest on tax deductions.

Consequently, because they can’t see how tax dollars and wealth transfer occurs at those high corporate levels, there is a tendency to criticize the things that they CAN SEE – a poor person begging on the street corner, someone using an EBT card; a poor person getting free medication due to Medicaid and/or “Obamacare.” They see people getting FREE stuff when they are barely scraping by and it makes them crazy mad.

Put another way, the incredible wealth and income benefits, tax deductions, and incentive programs that the richest members of society have access to are largely INVISIBLE to most working people. People getting government assistance, however, are HIGHLY VISIBLE and are thus much easier to judge. This is why they become a target for social wrath.

Sources:

Information about Gilliam’s “Welfare Queen” experiment can be found in an article published by the author in Harvard University’s Nieman Report, which can be accessed here.

Read more about the Brushton New York arrests here.

The Washington Post article with data published by the CBPP study can be accessed here.

Article by Stephen Pimpare, “Laziness Isn’t Why Poor People Are Poor.” Pimpare is the author of “A People’s History of Poverty in America” and the forthcoming “Ghettos, Tramps, and Welfare Queens: Down and Out on the Silver Screen.” He teaches American politics and public policy at the University of New Hampshire.

“6 Things Paul Ryan Doesn’t Understand About Poverty (But I Didn’t Either),” by Karen Weese

Help Overcome Misinformation, Denial, and Cognitive Dissonance

Many of you who are reading this may be coming by a lot of this information for the first time. It is likely you have numerous years under your belt, where you believed to be true a lot of the things the data here clearly dispute. Given this, it is possible you may not be ready to give up those beliefs. In the scheme of things, you might even go so far as to weigh your personal opinions against the data, and then elect to simply dismiss the data. If you do this, just know there are some very deep and powerful psychological reasons operating that may be preventing you from doing so.

In this instance, the psychological defense mechanism of “denial” is operating in conjunction with “cognitive dissonance.” Cognitive dissonance, according to psychologists, is the resulting mental state of stress/discomfort that occurs when someone simultaneously holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values. Thus, the pre-existing beliefs, ideas, and values become contradicted by the new information; in order to resolve the mental stress, the individual simply dismisses/denies the new information.

According to Stephen Pimpare, denial serves a few functions.

“First, it’s founded on the assumption that the United States is a land of opportunity, where upward mobility is readily available and hard work gets you ahead. We’ve recently taken to calling it grit. While grit may have ushered you up the socioeconomic ladder in the late 19th century, it’s no longer up to the task today. Rates of intergenerational income mobility are, in fact, higher in France, Spain, Germany, Canada, Japan, New Zealand and other countries in the world than they are here in the United States. And that mobility is in further decline here, an indicator of the falling fortunes not just of poor and low-income Americans, but of middle-class ones, too (Pimpare). To accept this as reality is to confront the unpleasant fact that myths of American exceptionalism are just that — myths — and many of us would fare better economically (and live longer, healthier lives, too) had we been born elsewhere. That cognitive dissonance is too much for too many of us, so we believe instead that people can overcome any obstacle if they would simply work hard enough (Pimpare).

Second, to believe that poverty is a result of immorality or irresponsibility helps people believe it can’t happen to them. But it can happen to them (and to me and to you). Poverty in the United States is common, and according to the Census Bureau, over a three-year period, about one-third of all U.S. residents slip below the poverty line at least once for two months or more” (Pimpare).

Third — and conveniently, perhaps, for people like Chaffetz or House Speaker Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.) — this stubborn insistence that people could have more money or more health care if only they wanted them more absolves the government of having to intervene and use its power on their behalf. In this way of thinking, reducing access to subsidized health insurance isn’t cruel; it’s responsible, a form of tough love in which people are forced to make good choices instead of bad ones. This is both patronizing and, of course, a gross misreading of the actual outcome of laws like these” (Pimpare).

To conclude, Pimpare offers the following:

“There’s one final problem with these kinds of arguments, and that is the implication that we should be worried by the possibility of poor people buying the occasional steak, lottery ticket or, yes, even an iPhone. Set aside the fact that a better cut of meat may be more nutritious than a meal Chaffetz would approve of, or the fact that a smartphone may be your only access to email, job notices, benefit applications, school work and so on.

Why do we begrudge people struggling to get by the occasional indulgence? Why do we so little value pleasure and joy? Why do we insist that if you are poor, you should also be miserable? Why do we require penitence?

People like Chaffetz, Ryan, and their compatriots offer us tough love without the love, made possible through their willful ignorance of (or utter disregard for) what life is actually like for so many Americans who do their very best against great odds and still, nonetheless, have little to show for it. Sometimes not even an iPhone.”

At the end of the day, there are a lot of different ways we might tackle poverty. The problem is, we can’t make any progress until the vast majority of people in society are willing to take a hard look at how their thinking too often diverges from reality on the matter; they must be willing to give up many of the assumptions they have about who is poor, on welfare, etc.

In short, they will need to set aside these beliefs and prejudices that are emotionally satisfying, but not informed by data and research; they need to begin to try to envision what the world really feels like for families living in poverty every day.

How might your own thinking about social welfare benefits and poverty be shaped by family perspectives, media narratives and social media imagery? How might these sources of information potentially influence how people understand “who is poor” in the United States? How might those understandings influence ideas about how to fix the problem?

Were you surprised to learn that statistics document there are more white people that receive food stamps and other social welfare benefits than African Americans?

Do you trust poor people who ask you for money? Do you think that most poor people are trying to get over on the system?

Why do you think it is that programs that benefit poor people (Food stamps/SNAP benefits) are referred to as “welfare,” but other programs that are similarly classified as public assistance are not thought of as “welfare.” This includes benefits like the home mortgage interest deduction, unemployment compensation, and the GI Bill. And what about other benefits that tax dollars pay for like capital gains tax write-offs and incentives and subsidies paid to corporations? Which of these categories of benefits do you imagine costs taxpayers the most? Benefits for poor people or benefits paid to wealthy people? As for the latter, why don’t we think of these benefits as “welfare,” considering that taxpayers pay for them too, often at a far greater cost?

Consider the following: Are you more concerned with the fact that a very small number of “undeserving” folks might “cash in” and get a “free lunch” as a result of efforts to promote less restrictive school lunch programs or are you more concerned with guaranteeing that not one single “undeserving” child gets a free meal? What is most important to you?

Why do you think people get upset about poor people receiving aid and benefits that are far less costly in terms of total dollars than, let’s say, other government programs, i.e. military spending, agriculture subsidies, and tax incentives for people and/or corporations? (see the list below)