The Significance of Others

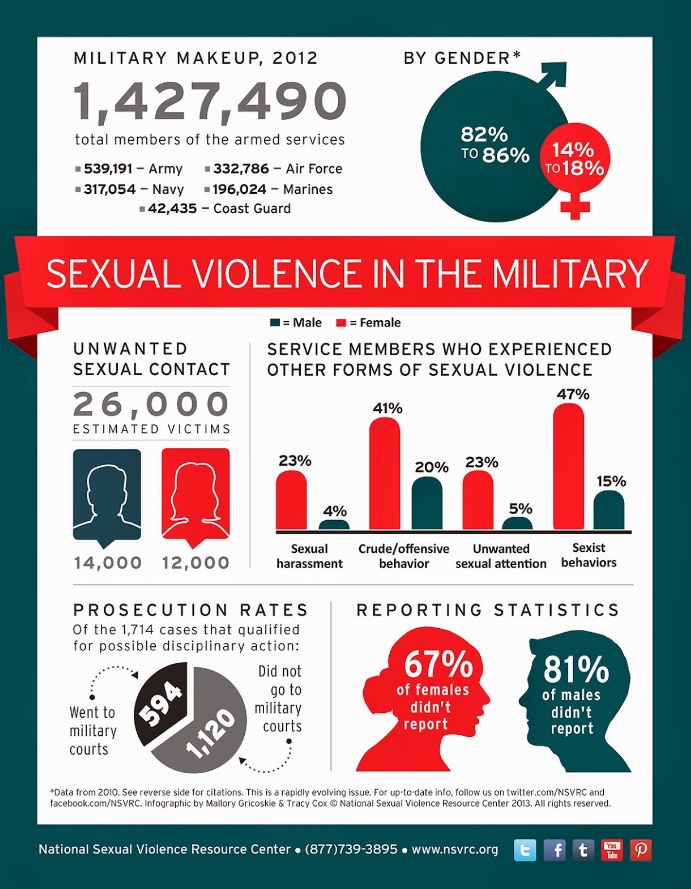

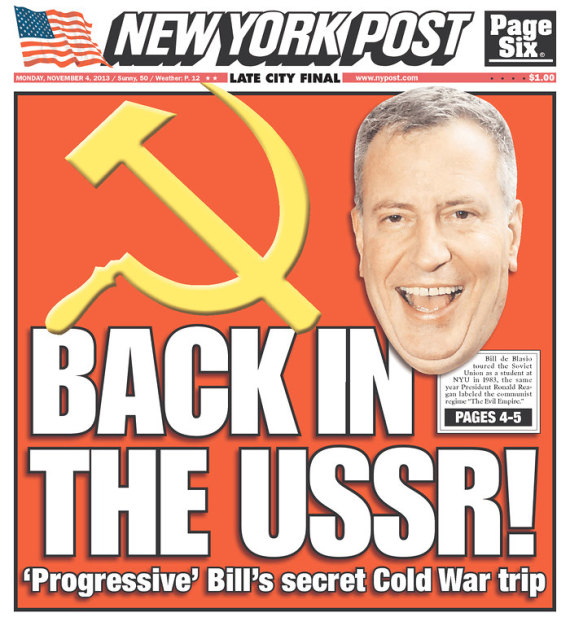

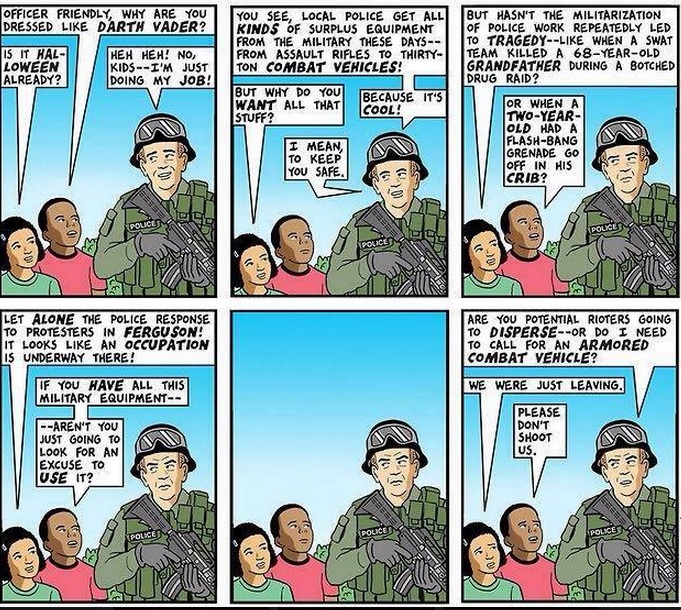

In the summer of 2014, after a string of violent incidents involving police officers killing unarmed civilians, a number of different counter-demonstrations supporting police officers were circulated in social media. For example, consider the photo above published by the New York Post, which shows Teachers from Staten Island wearing their NYPD t-shirts as a show of support for police officers shortly after Eric Garner’s death [he died when a police officer applied a chokehold to subdue him for selling loose cigarettes]. While a number of teachers cited the reason for wearing the shirts was to protest their union’s support for an Eric Garner rally, there were others who criticized their peers for the public display and the timing of it, which they felt was potentially disrespectful of many of their student’s feelings.

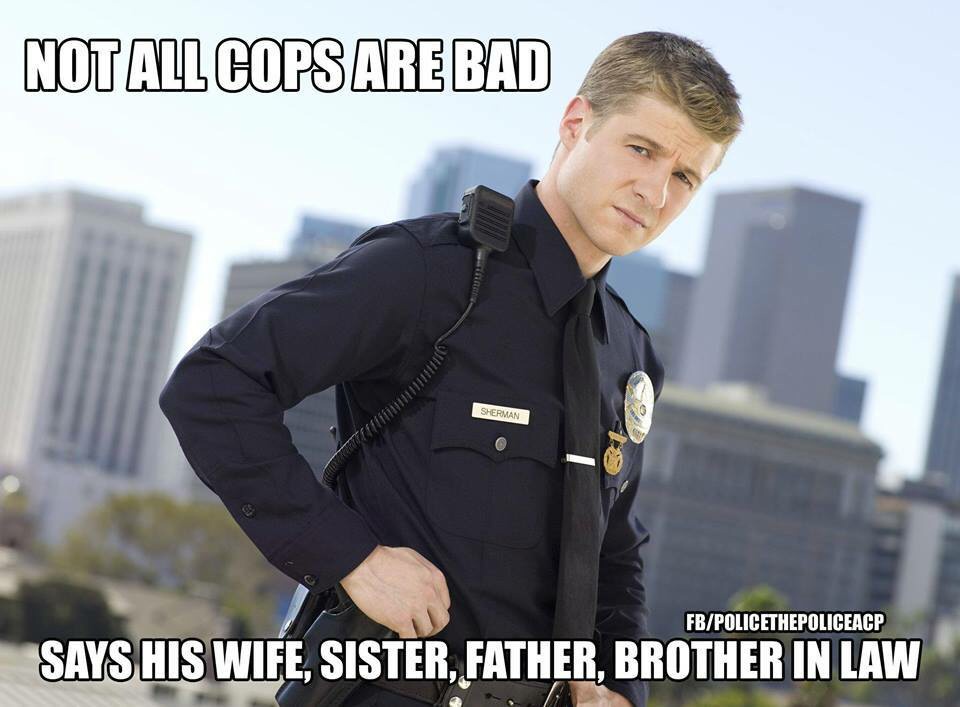

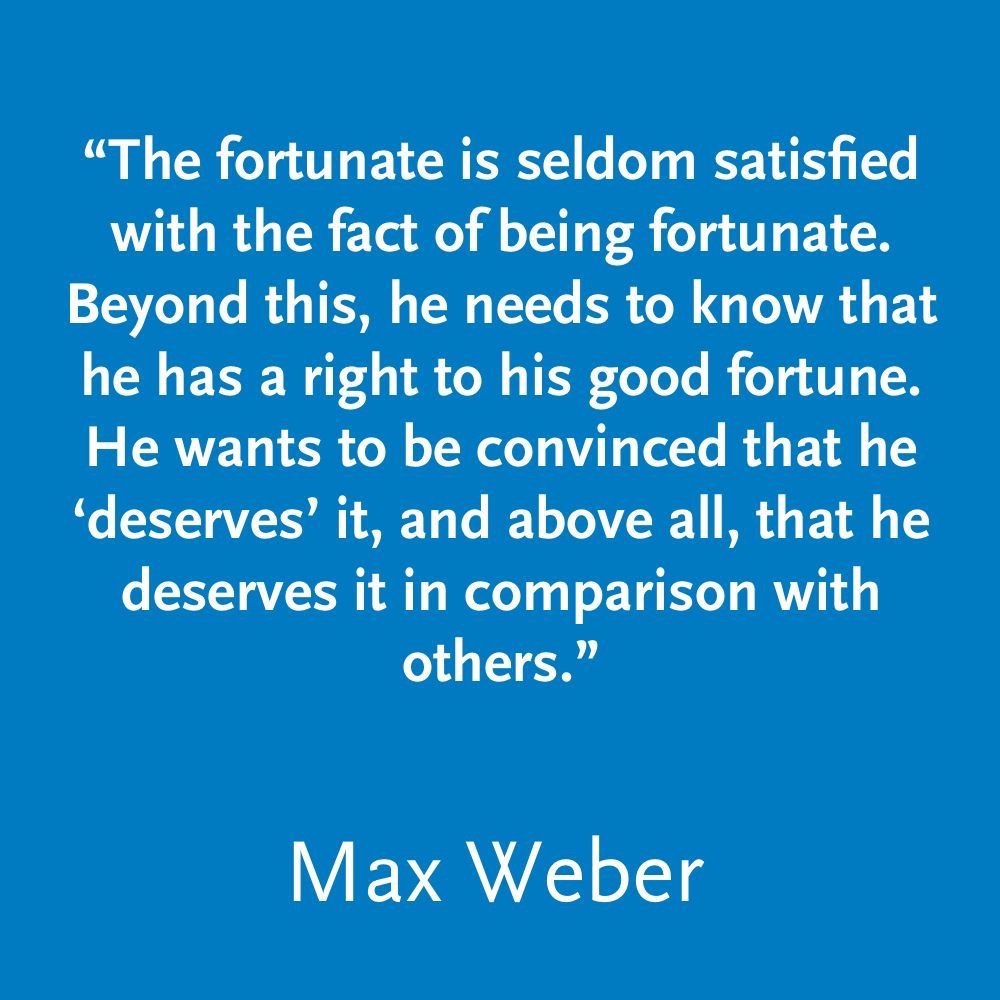

Not surpisingly, given that the overwhelming number of police officers working in the United States are white men, their most passionate defenders are correspondingly more often than not white women – wives, sisters, girlfriends, mothers, and daughters. They are all in a word – family. The overwhelming whiteness of the group photo is doubtless the most powerful message it conveys (even if it is unintentional). Among the arguments typically offered by family members rallying to the defense of police officers are claims such as “you don’t know them like we do,” “police should always be respected because they are honest, hard-working people with difficult and dangerous jobs,” and “it’s only a few bad apples that get all the attention.”

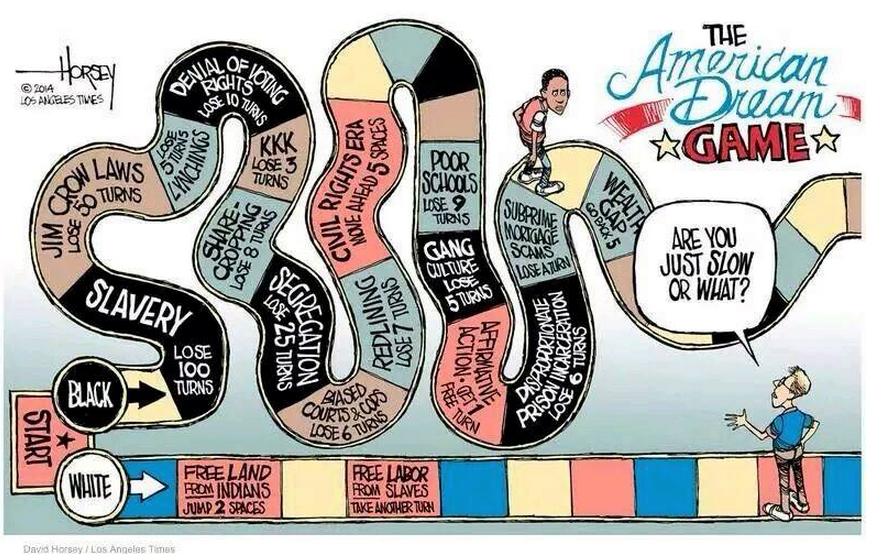

This particualr photograph demonstrates how the politics of race, class, and gender are deployed in what I call the “post-traumatic economy of militarized law enforcement.” Economy here is suggestive of a relational ontology between people, images, objects, and things; it is post-traumatic in the sense that the visual imagery demands we see, recognize, respect, and honor police officers and at the same time not “see” social divisions based on race, class, and gender. Militarized policing, in this respect, inscribes itself as a trauma on the bodies of both those who police and those who are policed, even when the traumatized don’t register recognition of their trauma.Compulsory forgetting, witnessing without seeing, and testifying without speech are all symptomatic of how militarized law enforcement manifests itself through a psycho-social process that relies on shock ,dispersal, and repression to elude understanding.

In what amounts to nothing less than a stunning reversal of the more traditional defense of “white womanhood,” the above photo suggests that a defense of “white manhood” concomitant with the defense of white womanhood might be asserting itself as a social bulwark against encroaching “otherness” represented by poor and minority ethnic communities.

Daddy’s Little Girl

Pictured below is Kathryn Knott, the daughter of a Philadelphia area police chief, Karl Knott. Her behavior was cited recently in the media, if only because in this particular case she served as her own documentarian. As noted above, Knox to some extent embodies the increasingly prevalent trend among police family members to engage in the defense of “white heterosexual manhood.” Not surprisingly, we find her described by her lawyer among others as “a young woman who’s never been in trouble” and as a girl who “comes from a wonderful family” with a law enforcement background.

As it turns out, Knott was arraigned alongside two male companions for “aggravated assault, criminal conspiracy, simple assault and recklessly endangering another person” when a group she was traveling with was caught on video beating two gay men in Philadelphia earlier this month. Knott’s Twitter feed only added to the social media outrage when it revealed a different side of her character than the one portrayed by her lawyer.

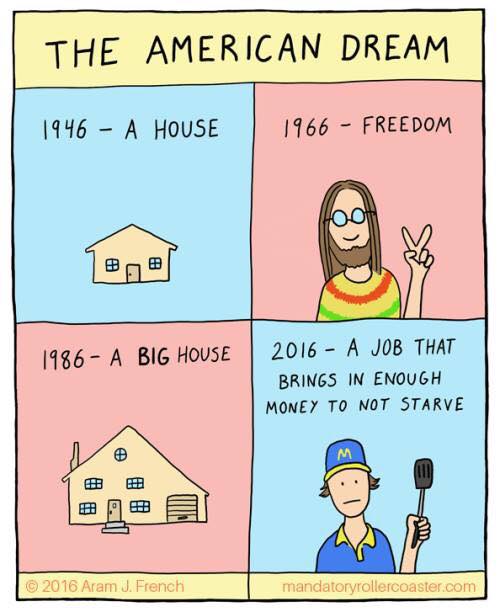

Taken altogether, it might be productive to reflect on how the post-traumatic economy of militarized law enforcement reflects the history of racial segregation, economic inequality in the United States. Think about the historic role played by law enforcement in policing race, class, and gender boundaries; boundaries that continue to be challenged, as evidenced by the ongoing conflict that unfolds daily across the social landscapes of our city streets and towns. As the photo and tweets remind us, it is simply not possible to fail to notice the overwhelming white power structure that predominates in police departments like those in Ferguson, Missouri as well as in places like Philadelphia and Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

Discussion Questions

What are we to make of social patterns as they relate to issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality when it comes to local practices that involve community policing?

How do you account for the disparities that you see or hear about when it comes to issues that involve the police? Do you think there is a problem with police behavior, or do you think the reporting of these incidents is exgaggerated by people who are simply “playing the race card?”

Do you count among your own friends and family members of the law enforcement community? And if so, how might that impact as well as infomr how you see and interpret conflicts like those taking place in Ferguson, MO, Cleveland, OH, Baltimore, MD, and New York City?

Do you find it difficult to reltate to people and protesters in places like Ferguson, where the lived experience of individuals might contradict and/ or reside far outside your own lived experience?

![TBox] Taxi to the Dark Side 2007.avi_snapshot_00.38.52_[2013.09.27_02.37.16] (1)](http://sandratrappen.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/TBox-Taxi-to-the-Dark-Side-2007.avi_snapshot_00.38.52_2013.09.27_02.37.16-1-1024x585.jpg)