The War at Home

From Occupy Wall Street to Ferguson Missouri and beyond, the work of photojournalists increasingly are revealing a stark truth: the United States is engaging in a wide-scale re-engineering of its domestic police forces. The creeping militarization, however, did not occur in a vacuum; it has a history that represents a martial miscegenation of sorts, where the ethic of “serve and protect” once associated with civilian police appears to have become merged with the “hunt, kill, destroy” ethos of military forces. But this didn’t happen overnight. There is a history that sets the stage for a process that has become accelerated in recent times.

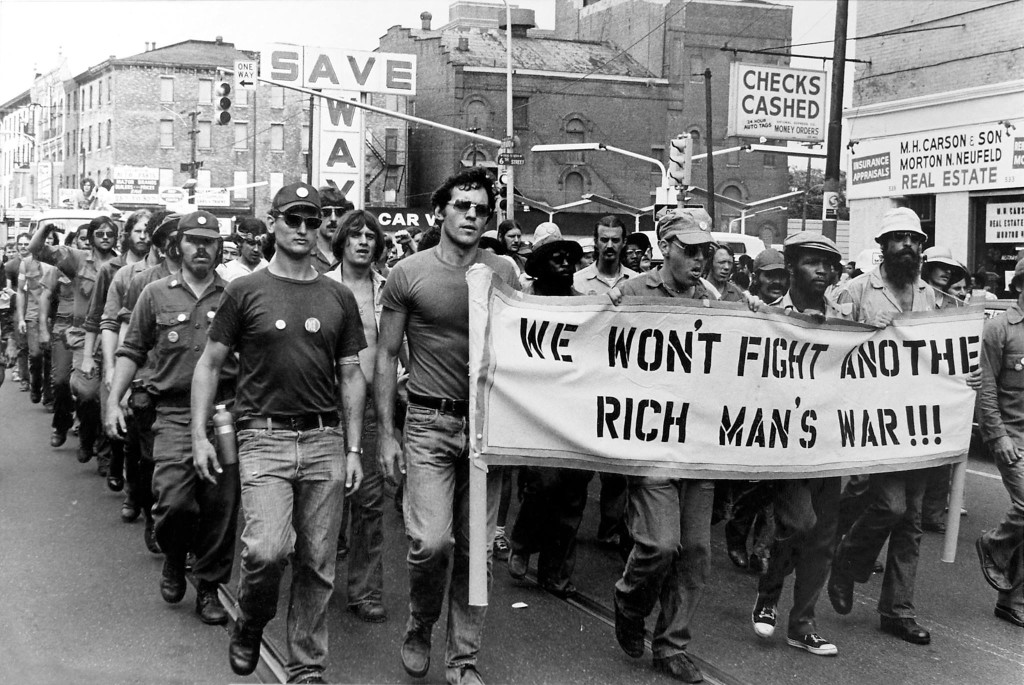

Historically in the United States, private police forces were first employed by wealthy plantation and landowners. These “slave catchers” were hired and paid to hunt African-Americans. Critics argue that we never really escaped this past, even if the legacy connections are not always obvious. To trace these developments, we have to follow the money. Wealthy corporations and allied powerful interests have always employed the police to protect their assets. During slave times, of course, those assets did not simply include material goods they also included people, who were considered property.

Today, the same people continue to pay for private security and invest in public police forces to protect private property [local example: The Waterfront shopping plaza on the river in Homestead is protected by a full-time police police officer, whose expenses are reimbursed to Homestead borough (paid for) by the shopping complex].

There is a racial ideology (spoken and unspoken) that often drives these developments, including resource allocation. While there is presently a contentious debate raging in the U.S. with regard to police funding – some people say we need more funds and others say there is too much funding, there are no easy answers. The problem is socially entrenched. What you think about police funding is going to derive in many respects from your own personal experiences. Do you have police in your family? Were you the victim of a crime? Do you live in a deteriorated neighborhood? Do you live in a racially homogeneous social space?

The police funding equation is not as simple as “more cops (funds) = less crime.” As the research indicates, money is not always an effective predictor of public safety. The data, in fact, demonstrate in a fairly consistent way over time that fewer than half of serious crimes are reported to police. Few, if any arrests are made in those cases. Only about 11% of all serious crimes result in an arrest, and about 2% end in a conviction (Nissen, 2020). Simply put, there are many local complex social factors that impact the degree to which police can be effective in their jobs.

Police Militarization

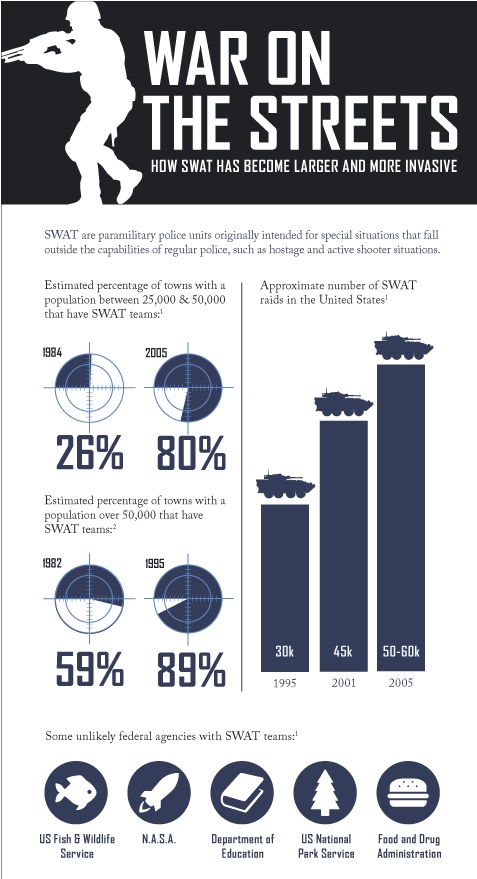

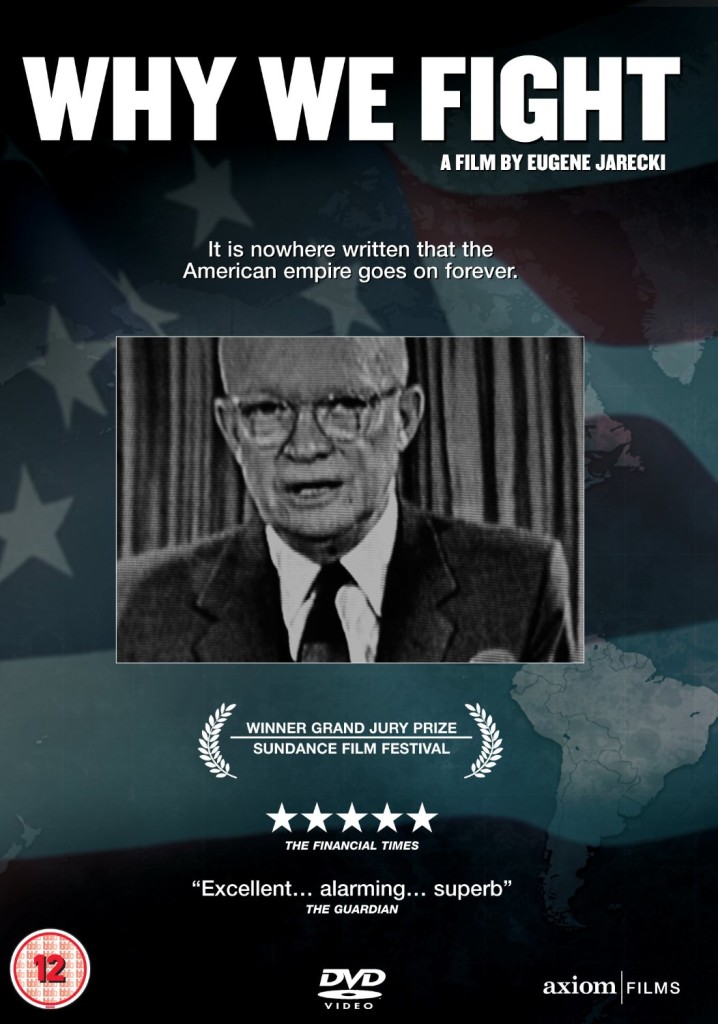

Scholars have documented the trend in the outfitting of local domestic police with military-style gear (the exorbitant costs of which are paid by the U.S. taxpayer) as having started with the Reagan administration’s “war on drugs. This policy failure is, however, by no means consigned to the past, as it rages on, fueled by another policy disaster – the amorphous “war on terror,” which was launched to coincide with the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan.

It is worth noting that we cannot blame one political party while holding the other blameless. Police militarization is truly a bipartisan project; one that has occurred within a socio-political context, where up-armoring of police is but one manifestation of a comprehensive plan to address a wide range of security issues in the wake of 9-11. Both Democrats and Republicans in Congress have embraced a politics of fear in order to 1) motivate voters and 2) avoid being seen as soft on crime and terrorism. The results are staggering in scale to the extent that they encompass NSA surveillance, drone wars, and the increasing privatization and expansion of the prison/carceral state.

The New Military Urbanism

Author Stephen Graham (2011) discusses the multiple ways in which the “new military urbanism” might be seen in cities like New York City, Baltimore, and London. The development is typified by the increasing proliferation of large militaristic SUVs on city roads, an increase in the number of militarized borders and surveillance zones within and around urban areas, amplified collaboration between military, intelligence and police organizations, as well as patterns of linking neoliberal logics with security infrastructure (i.e. EZ Pass monitoring, photo enforcement of traffic laws). Perhaps most disturbing among these developments is the tendency to conflate internal urban ethnic minority groups with external enemies of the state (Graham, 2011).

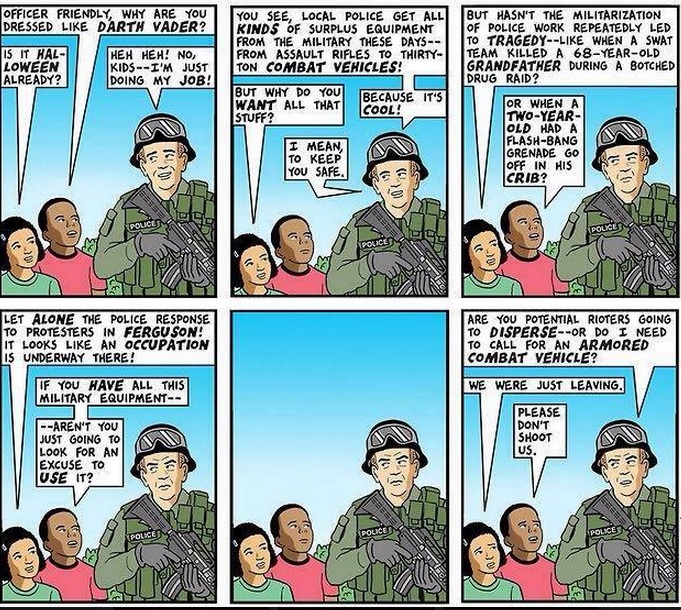

Recent research on public attitudes toward police and policing suggests that the Mayberry R.F.D. notion of “officer friendly” has been profoundly ruptured and perhaps along with it the shared public sense of a social contract. Public trust, not surprisingly, goes out the window when policemen patrol neighborhoods as if they are in the middle of Iraq or Afghanistan.

SWAT

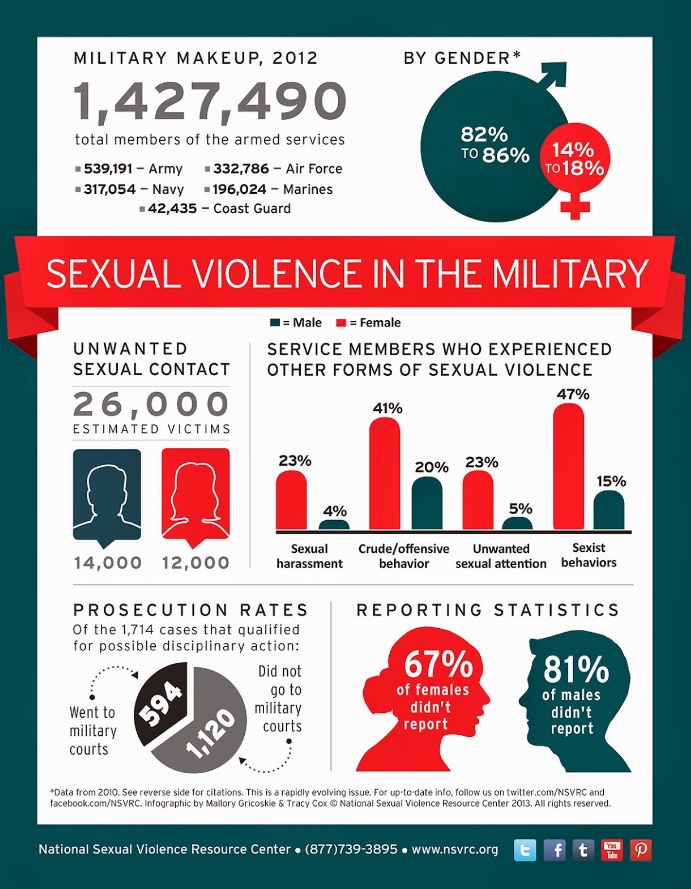

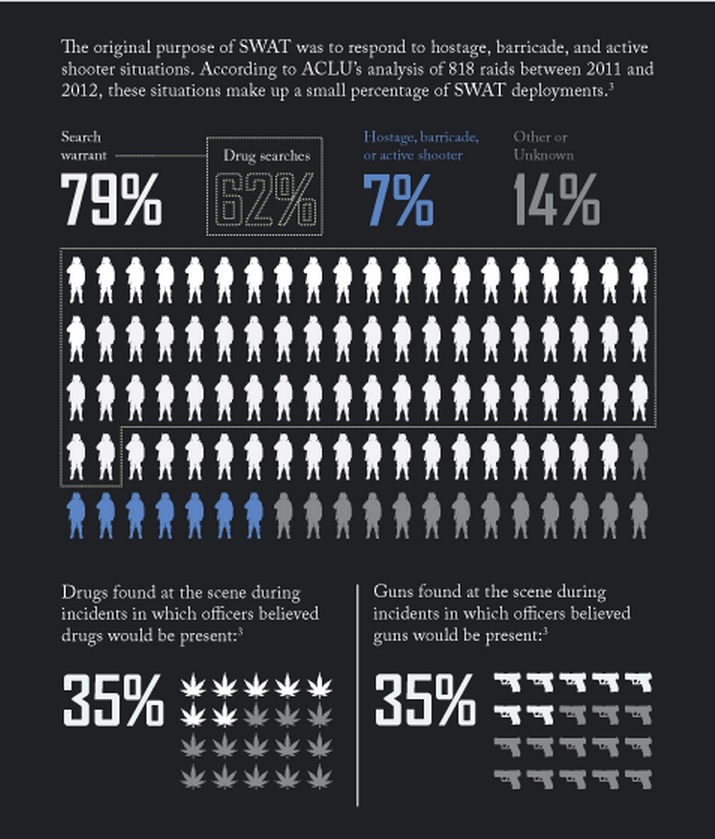

In a report entitled “War Comes Home,” the American Civil Liberties Union called attention to how, over the course of the last 25 years, the number of SWAT team raids in the United States dramatically escalated. Their report found that nearly 80% of all SWAT raids it reviewed between 2011 and 2012 were deployed to execute a search warrant. Bear in mind now, this type of “invasion” tactic is being routinely used against people who are only suspected of a crime. Police, in other words, are using a tactic proven to result in significant injury and property damage as a first option and not as an option of last resort.

Who are the targets of these raids? Statistics reveal, more often than not, it’s the doors of blacks and Latinos that are broken down. The same ACLU report found that when they could identify the race of the person/people whose homes were broken into, 68% of the SWAT raids against minorities were undertaken in order to execute search warrants for drugs. The figure dropped to 38% when it came to whites. This pattern was established in spite of the well-documented fact that blacks, whites, and Latinos all use drugs at roughly the same rates. SWAT teams, it would appear, are disproportionately applying their specialized skills to communities of color. What this essentially does is take racial profiling and “stop and frisk” to a terrifying new level.

Organizational Culture

Given these developments and that fact that cities can be dangerous places for everyone. There are questions that remain to be answered. What do we want our police departments to accomplish? Is their mission “Serve and Protect?” or is it “Search and Destroy?” The public seems unsure.

Many among the public prefer to live in nostalgia. Policing, in their view, resides in a mythical past, where the police are always helpful and friendly – like a neighbor to be trusted. Doubtless, there are individual police who are committed to upholding these ideals. Statistical patterns, however, indicate a different reality is emerging.

Strong opinions that exist on both sides of the “good cop”/”bad cop” divide. On the one hand, there are those who defend the “blue line” as they argue #bluelives matter and #notallcops. The problem with the #notallcops argument is that it reduces systemic institutional violence to an individual problem. That is, it suggests we might simply remove the few “bad apples” to fix the problem. Policy accountability efforts are often painted with the broad brush of being “anti-cop.” This type of thinking, unfortunately, gets in the way of prudent action to bring about meaningful institutional level reform through policy change.

On the other hand, many argue that police behavior has jumped the shark; that norms for professional conduct are deteriorating and people are being needlessly harmed and in many cases killed due to police violence, leadership failures, and the failure of police organizations to regulate themselves. From the never-ending stream of videos, showing unarmed black men and children being shot, including the strong-arming/bullying of a nurse, and in one instance, the killing of a woman, Sandra Bland (who refused to put out her cigarette), critics allege the cops are out of control and nothing is being done about it.

In addition to these developments, statistics document contemporary uses of SWAT occur at a rate that is 25 times more frequent than in the 1980s. Again, these happenings did not occur in a vacuum. Violence has a history and a memory. From the original slave patrols conducted in the wake of the U.S. Civil War, through the policing of Jim Crow laws in the old South, and now the involvement of U.S. soldiers in wars overseas (many of whom have become police offices upon return), policing forces are not surprisingly militarized as a result.

The policy apparatus that contributed the most to the funneling of millions of dollars into militarizing local law enforcement was the federal 1033 Program. The 1033 Program provided surplus military equipment to state and local policing agencies. According to a report published by The Guardian, the 1033 program has provided 12,000 bayonets, 5,200 Humvees and 617 mine-resistant ambush protection vehicles (MRAPs) to local police agencies across the United States.

Originally intended for use in counter-narcotics and counter-terrorism operations, military equipment is increasingly being used against political protesters and other local civilian populations. These weapons of war did not magically “appear” on our streets–they proliferated because the federal government paid for them and facilitated their use.

With that, local law enforcement reveals signs they are evolving into a domestic army. Things like bodily comportment, equipment, tactics, command structure, a willingness to lay hands on the public and disregard for basic constitutional protections all indicate that this is happening. Ironically, aggressive foreign policies exercised by the United States that were once universally applauded by Americans, who saw the activity as necessary to “keep us safe” and “spread democracy,” produced what philosopher Michel Foucault called a “boomerang effect.” Violence exercised abroad ran it’s course and finally came home to roost (Graham, 2011).

Here are a few statistics worth noting:

In 1980, there were approximately 3,000 SWAT raids in the United States. Now, there are more than 80,000 SWAT raids per year in this country.

79% of the time, SWAT teams are deployed to private homes.

60% of SWAT raids in one ACLU study were shown to target homes for drugs/drug use, not to save a hostage, respond to a barricade situation, or neutralize an active shooter.

65% of SWAT deployments feature the deployment of a battering ram, boot, or other explosive device to gain forced entry to a home.

62% of all SWAT raids involve a search for drugs.

50% of the victims of SWAT raids are either black or Latino.

36% of all SWAT raids indicate that no contraband is found by the police.

35% of the time, in cases where it is suspected that there is a weapon in the home, police do not find a weapon.

7% of all SWAT deployments are for hostage, barricade or active-shooter scenarios.

More than 100 American families have their homes raided by SWAT teams every single day.

Even small towns deploy SWAT teams now: 30 years ago, only 25.6 percent of communities with populations between 25,000 and 50,000 people had a SWAT team. Now, that number has increased to 80 percent.

This is a Public Policy Failure

When the police are used as the “one size fits all” policy arm to address racial injustice, poverty, homelessness, opioid overdose, mental health problems, and inadequate access to healthcare, neither the public nor the police are served. The police are set up to fail and be hated by the public. In this environment, no one can ever feel “served and protected.” Everyone is at risk.

Essentially, we’re putting all our human resources and funding into one bucket (the police) and asking them to do everything (that they are not trained to handle) that more specialized institutions could address for far less money with higher rates of effectiveness. The police, in turn, ratchet up the violence and try to contain problems with the only tool they have – mass incarceration.

Put another way, we “defunded” education and healthcare and gave it all to the police without ever loudly proclaiming that we did this; we provisioned one institution with funds from the others and made our problems worse, not better. That the public largely continues to support this failed approach (obviously, there are pockets of resistance) says something important about the public. What drives them to support failed policy? Why do people time and again choose righteous indignation over support for interventions to change the system?

Sources

Cities Under Siege: The New Military Urbanism, by Stephen Graham (2011)

War Comes Home: The Excessive Militarization of American Policing, published by the American Civil Liberties Union (2014)

For more on the history of SWAT, link to the New York Times report “SWAT: Mission Creep” w/video.

Discussion Questions

What do you think about these statistics? Do these developments alarm you?

What do these trends say about what it means to live in American society?, considering how rapidly we are transferring the weapons of war into the hands of police to be used on U.S. citizens?

Do you think it is a good idea for so many police to have access to/deploy weapons of war on our streets? (to be used on U.S. citizens)?

![(Steve Bosch/Vancouver Sun) [PNG Merlin Archive]](http://sandratrappen.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/wealthy-wilmas-1024x866.jpg)

![TBox] Taxi to the Dark Side 2007.avi_snapshot_00.38.52_[2013.09.27_02.37.16] (1)](http://sandratrappen.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/TBox-Taxi-to-the-Dark-Side-2007.avi_snapshot_00.38.52_2013.09.27_02.37.16-1-1024x585.jpg)